Since it’s becoming harder for brands to avoid taking a political stance on issues, Warwick Cairns from The Effectiveness Partnership looks at the relationship between taking a stance and effectiveness -- and how brands can navigate this increasingly rocky terrain.

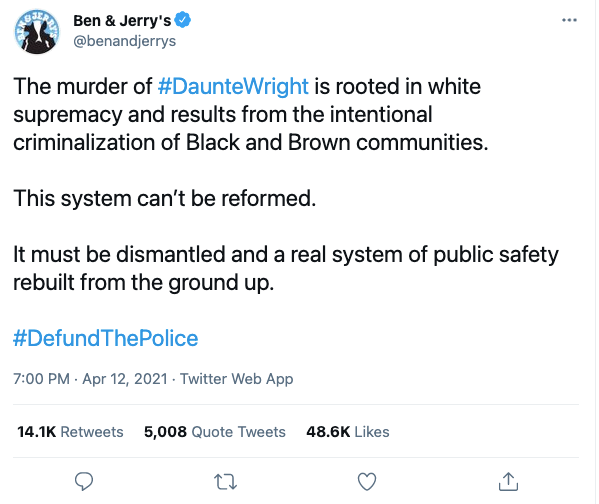

Some brands have always taken a political stance on matters of principle, but increasingly it’s becoming the rule rather than the exception. Today, growing numbers of CMOs on both sides of the Atlantic believe it’s appropriate for their brand to have a say on politically-charged issues. This month alone, Ben & Jerry’s tweeted its support for defunding the police in wake of the death of Duante Wright, and dozens of US corporations have opposed new and proposed laws that would put new voting regulations in place. But what does it mean for effectiveness?

We’ve become used to ‘activist’ brands straying into politics in areas that touch on their businesses, like the outdoor clothing manufacturer that gets involved in political lobbying, to preserve the Great Outdoors for its customers.

This past year, however, brand activism has taken on new momentum, and spilled out way beyond category boundaries. At last count, according to the CMO Survey, 27.7% of US CMOs said they believed it acceptable for brands to have a political stance.

Today, you can buy sports shoes that take a stand, or a knee, in support of Black Lives Matter. You can eat at fast-food joints that affirm your faith in traditional marriage. You can even get guidance on gender politics with your razor blades.

There are always going to be different views on the rights and wrongs of particular causes, but there is one question that needs to be asked: Does brand activism build effective businesses?

The first place to look is at the numbers. And those numbers say, it all depends.

In a win for the progressive team, Nike reported an immediate 13% sales spike following its support for Colin Kaepernick, the NFL quarterback who knelt for the national anthem in protest at racial injustice.

On the other side of the coin, when Chick-Fil-A was targeted by LGBTQ groups on account of its chairman’s Southern Baptist views on marriage, the company refused to back down. The row spread around the world: a UK branch had its lease revoked just eight days after opening. But the controversy did nothing to harm Chick-Fil-A’s position in America’s “chicken wars”. In fact, share actually increased, to the point it was challenging Subway as the country’s third-biggest fast food brand.

Brand activism is often a response to changing consumer attitudes. But from a business effectiveness standpoint, what matters is who you’re doing it for, and why. Of course, some issues just matter. Democracy, for example. But when corporations start opining that democracy is not better served by limiting ballot drop-off boxes in the state of Georgia, then things get complicated.

Niche brands like Patagonia are in a fortunate position. They have values that are widely shared by the bulk of their relatively homogenous consumer base.

However, for mass-market brands unaccustomed to talking politics, it’s not so easy. Look what happened to Gillette when it set out to educate its users on toxic masculinity. The campaign racked up 20 million hits and got numerous likes and shares but it also polarised audiences. As category leader, with over 50% share, the impact on its broad, existing base – men who shave – was always going to be mixed. Customers who liked the ads felt better about their brand, but that didn’t necessarily make them buy more razors or shave more often. But of the customers who were annoyed by the ads, some were ‘nudged’ towards rivals like Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club. The net effect: a decline in brand penetration and a reduction in revenue.

The problem for brands is that it’s becoming harder to stay above the fray, even if they want to. Research by the thinktank More In Common shows that the online culture wars are mostly fought by tiny minorities of the population – but they are the noisy and influential ones, pitching highly motivated and engaged progressive activists (8% of the US population) against equally uncompromising devoted conservatives (6%).

In today’s climate, it’s easy to get caught up in the heat of the moment. But a growing number of brands find themselves damned if they act, and damned if they don’t. So maybe, instead, it’s time to be patient, to take a moment to assess what your customers think your brand stands for.

If your customers mostly agree with your brand, and each other, on issues of the day, by all means speak out. For the rest of us, it’s worth looking back to 1937, to Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People”: Begin by emphasising – and keep on emphasising – the things on which you agree. Keep emphasising, if possible, that you are both striving for the same end and that your only difference is one of method and not of purpose.’

This means consumer research. It means identifying the strongest opponents of any stance you may wish to take, and exploring – and road-testing – ways to make them feel not just that it’s a good idea, but an idea they can feel ownership of.

Because at the end of the day, effective communication, and effective business, are about hearts and minds, not boycotts and banners.