Bandwagons have a bad name, but Warwick Cairns considers the potential risks and potential rewards of following the crowd.

It just seems, all of a sudden, that when it comes to the bandwagons we were confidently told would show the shape of things to come, many of them aren’t turning out to be quite the game-changers we were expecting.

Sometimes the experts can call things wrong, of course.

Back in 2001, there was a yet-to-be-unveiled personal transportation innovation that was going to change the world. Steve Jobs described it as ‘the most amazing piece of technology since the PC.’ Jeff Bezos called it ‘revolutionary’ and ‘infinitely commercial.’ Its founder, Dean Kamen, told Wired that it would ‘be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy.’ But when it eventually launched, the Segway turned out to be less what the car was to the horse and buggy, and more like the Sinclair C5.

“The most amazing piece of technology since the PC.” Steve Jobs

That might have seemed like a one-off error of judgement. But today, even many of the more mainstream ‘waves of the future’ are beginning to look somewhat less certain.

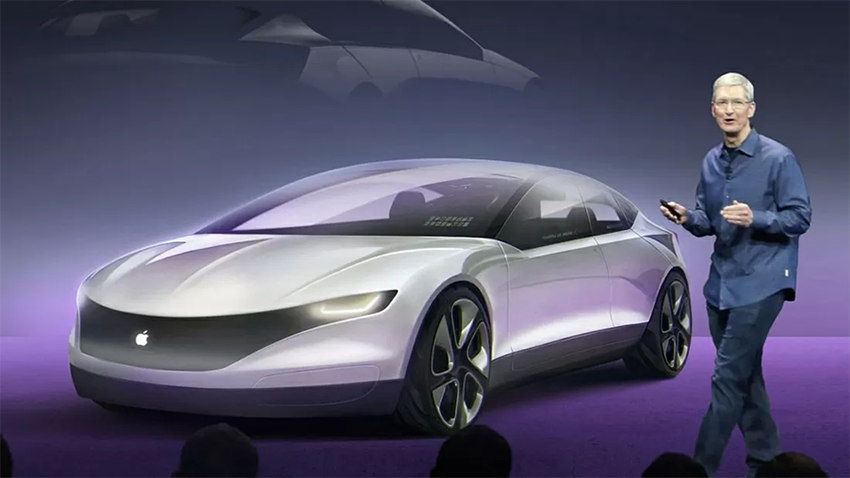

Electric vehicles, for one thing. Just this past month, Bloomberg announced that after ten years of R&D, and more than ten billion dollars in investment, Apple was finally pulling the plug on its prototype EV, Project Titan, and releasing or redeploying the more than 2,000 employees working on the scheme. Many of them had previously been poached from the big car manufacturers on huge salaries.

Project Titan (R.I.P)

The very next day, Canadian billionaire Lawrence Stroll, executive chairman and biggest shareholder of Aston Martin, announced he was postponing the company’s plans for an all-electric supercar. He said, “All our technologies are in place… Everything is in place. The only thing that isn’t in place is the consumer demand.” Ah yes: consumer demand.

Meanwhile, and elsewhere, we’ve seen all kinds of other ‘coming waves’ failing to break. We’ve seen vegan cafes either closing down or, in some cases, announcing plans to start selling meat. We’ve seen growing numbers of high-street zero-waste stores going bust.[1] [2] [3] We’ve seen the whole hipster-friendly plant-based milk sector suddenly slipping into decline after years of double-digit growth.

It’s worth taking a look at how we’ve come to this point, and the lessons that can be learned.

James Goldsmith once said ‘If you spot a bandwagon, it’s too late,’ but for most of us that isn’t necessarily the case. In reality, when we spot a trend that all of our friends are desperate to climb on to, our first instinct is often to want to get on board too. Electrify that car. Milk those almonds. It’s what’s known as the Bandwagon Effect. Psychologists say that all of us, to varying degrees, often feel, believe and do things because other people are doing them, and we don’t want to be left out. Oftentimes we may even ignore or override our own instincts or beliefs in order to be part of it. It makes sense: for most of our evolutionary history it’s always been more in our interests to be wrong in good company than right and cast out into the wilderness.

As businesspeople, as marketers and as human beings, we’re never going to be immune from the bandwagon effect. Nor would that necessarily be a good thing. When something big is happening it often pays to be at the forefront of it. If you can get yourself into the right place at the right time, a lot of people are going to want a piece of what you have. You can achieve amazing personal and financial success from it.

But at the same time, if you identify too strongly or completely with a trend that lacks foundation it can leave you intensely vulnerable when the herd decides to head elsewhere.

The problem, and the vulnerability, lies less in where your particular bandwagon happens to be heading, and more in the gap people have to cross in order to get there.

If you imagine two separate circles on a sheet of paper. Circle A is where you are. You might be selling petrol cars, for example. Or you might be selling smartphones and laptops. Circle B is where you want to be. The next Tesla, or whatever.

Too many people, and too many brands, give too much thought to getting to B, and not enough to how they’re going to bridge the gap between the two.

To take vegan cafes as an example. Veganism has been one of the most significant cultural bandwagons in the early 21st century. There are all kinds of environmental and animal welfare reasons why someone might want to encourage people to eat less meat. In 2023, Bill Gates announced that ‘plant-based is going to be the future … and I want to be the person that plants the seed.’

“Plant-based is going to be the future.” Bill Gates

You can understand the fervour that drove entrepreneurs to open vegan food outlets – until you step back and look at the numbers. Because in the UK, strict vegans still make up just 3% of the population. Most of the things they consume, from milk-free cappuccinos to fake-cheese sandwiches – are a turn-off to much of the remaining population. That includes Britain’s vegetarians (7% of the population) and flexitarians (an astonishing 23%, if surveys are to be believed). Just a little more thought to bridging the gap with what the 97% wanted might have made all the difference to those failed businesses. It could have been as little as a splash of milk and a dollop of butter.

It's the same with electric vehicles. They’re smooth. They’re responsive. They’re silent. But when Aston Martin spoke to its existing and aspiring petrol-car owners, they found that drivers were still in love with “the sports car smell, feel and noise” of a petrol engine, and this was putting them off. If you jump straight to ‘buy electric’ without addressing the gap with where buyers are now, you’re going to be leaving a lot of customers behind.

This is where things get interesting. Because a number of brands are finally pulling back from being at the forefront of their respective bandwagons and exploring ways to re-incorporate elements of what people like about the present.

High-end car brands in particular are investing in sensory engineering to build back some of the psychological luxury that efficient, silent electric engines have taken out.

For its all-electric Continental GT, Bentley have recorded the sounds of hundreds of classic grandfather clocks and merged them with sounds from the car itself to create the ‘perfect’ dashboard clock tick for their interior soundscape. They’ve done the same with metronomes for their indicators.

Meanwhile, for its upcoming electric supercar range, Ferrari have found a way to amplify and deepen the sounds of the electric engine and reroute them to speakers at the rear. The result is a futuristic equivalent of the brand’s distinctive ‘exhaust roar.’

We all talk about bandwagons, from time to time. When we use the word it tends to be in a negative way, like it’s a bad thing. That’s not always necessarily so. What does matter, though, is that you make your move consciously and in full awareness of both the potential rewards and the potential risks. You should take care to build and sustain a connection between where your audience are now and where you want them to be. Because a bandwagon is no different from any other moving vehicle. When you climb on board it pays to mind the gap.

References

[1] Plastic-free shop makes 'difficult decision' to close down after six years

[2] The Little Green Larder: Dundee zero waste shop announces closure

[3] ‘We really made a difference’: Belfast shop to close as customers express regret