Emotional advertising is in vogue right now. But how much do we need to do and how much is too much? WARC was at Brainy Bar 7 to hear.

As we head into the Christmas season in the UK, brands are unveiling their narrative-rich, festive-cheer, penguin-toting emotional campaigns. Emotion is, indeed, the flavour of the month, and it was appropriate that somebody gather experts to shed light on the creative approach that has become synonymous with the season.

Brainy Bar is a busy event held at the headquarters of the ‘human understanding’ research agency Walnut Unlimited. Now in its seventh iteration, the evening continues to draw experts from both academic and business circles, offering nuanced, evidenced takes on the marketing implications of neuroscience, and most importantly, what to do with it.

Dr. Cristina de Balanzo is the consultancy director of Walnut Unlimited, and the instigator behind the Brainy Bar event. “Everyone talks about emotional advertising, everybody wants emotional brands,” she noted. In her analysis of the Cannes Creative Effectiveness Lions, which featured in WARC’s report on the awards, she observed that an emotional creative strategy was one of the common denominators of the winners, specifically the emotion of humour.

“Research draws a parallel between humour and what storytelling does in your brain: it puts the whole brain to work, activates memory processing and brings personal relevance,” Balanzo wrote. Done right, it can be incredibly effective; wrong, and a campaign can create a funny ad, but little else. “Behind the humour there is always a truth and this is what brands need to own: the brand insight that will support the correct brand attribution, otherwise the effectiveness and the long-term brand impact will be missed.”

Emotional basics

Emotions are there to keep us alive, explained Dr. Amy Milton, a lecturer in neuroscience at Downing College, Cambridge. Emotions help us to encode memories, which we store in order to help us to predict the future.

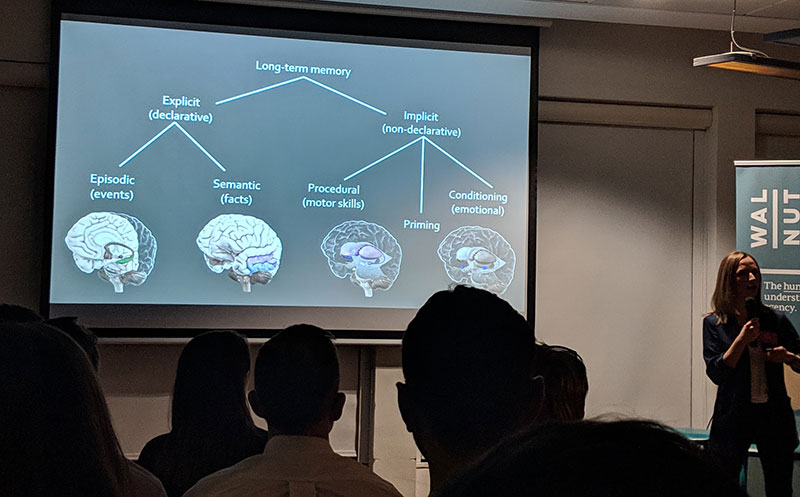

Milton pointed to the structures through which humans encode memories for the long term. Different types of memories jog different parts of our brains. Both are key to brands. In the hippocampus, we take in explicit memories – the memories we can recall and name: events and facts. Meanwhile, in the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure in the temporal lobe, we process the memories that we wouldn’t necessarily describe or name: our motor skills, or the emotional conditioning of our memories. “We are unconsciously surveying our environment all the time,” explained Dr. Milton, and if any cues in that environment spark our emotions, the more likely we are to encode them.

This means that a little bit of emotion is a good and useful ingredient, but there can be too much. In very high levels of emotional arousal, people’s attention tends to narrow. In the most extreme examples it narrows to a reaction triggered by the amygdala as the hippocampus shuts down. See, for instance, people held up at gunpoint who end up remembering the gun, but not the person that held it.

In an advertising context, this can have unintended effects.

Too much emotion

In 2014, Budweiser’s emotionally charged ‘Puppy Love’ ad premiered at the Super Bowl. The company's brand vice president, Jorn Socquet, subsequently claimed Budweiser “won the Super Bowl” with the most retweeted alcoholic beverage tweet ever and the most likes on a Facebook post ever from an advertiser. Ten months later, Socquet admitted that while “everybody loves the puppies, they have zero impact on beer sales…they don’t sell beer.”

Phil Barden, Managing Director of Decode, a research agency, argued that emotional arousal can help to predict virality, but warned that it’s not the same as effectiveness.

Emotions are dependent on whether people achieve their goals or not, and change in relation to those goals, said Barden. But “emotional advertising does have a head start” when it comes to resonating with audiences, as it can trigger physiological responses and activate associations and memories. He emphasised that emotion is “only a vehicle, not the motivational message itself”, and that there should be a combination of emotion and motivation to optimise communication effectiveness.

As such, Barden highlighted Les Binet and Peter Field’s distinction between rational and emotional advertising, and its root in the IPA Effectiveness Awards. Entrants must, to an extent, self-diagnose the ways in which their advertising works. “I would challenge the IPA to be more precise,” said Barden, and therefore render findings from the database subtler.

Making emotional ads

Every creative surely wants to make something that gets viewers as excited as John Lewis ads do, and every strategist wants to be able to demonstrate how their plan delivered results. Obviously, the science is crucial in developing and deploying an effective ad, but it shouldn’t dictate the construct or content of the ad, advised Justin Clouder, a strategy partner at TBWA\London, who noted how “the long shadow of John Lewis” hangs over most discussions of emotional advertising.

It’s crucial that the creatives are not bound by the science, and that it informs the strategy, but doesn’t hinder the work. None of this is even particularly new, he added, as emotions have functioned the same way in humans for as long as we can remember; the difference now is that we have the evidence. The irony of it all: now that we know why it works better than ever, it seems that people are listening to the evidence less and less.