Cathy Taylor, WARC's US Commissioning Editor, introduces the first Spotlight on Brazil, which examines several of the major trends that are facing brands in the country.

This article is part of the August 2021 Spotlight Brazil series, "A close look at LATAM's largest market." Read more

Looking at Brazil from a US perspective, it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that, especially these days, the two countries have a lot in common.

Both nations are going through a polarizing time in the political arena, with controversial figures – in Brazil’s case, President Jair Bolsonaro, and, in the US, former President Donald Trump – sitting at the center of frequent controversies, and being criticized by many commentators for their respective handling of the Coronavirus pandemic.

Similarly, the two countries – which are the two largest nations in the Americas by population – are awash in misinformation, especially regarding COVID-19. They are also both dealing with myriad issues relating to diversity, equity and inclusion, and the unfortunate related problems associated with major income inequality.

But as we launch our first Spotlight on Brazil, it would be a mistake to let those comparisons go too far: Brazil’s economy and culture may share some features with the US (and, indeed, many countries throughout the world) but it is wrestling with them in its own way.

Progress, optimism and reinvention

For all of Brazil’s problems, there are plenty of green shoots that point towards a society that is moving forwards, and that is infused with optimism.

As Ligia Barros from trends forecasting and analytics firm WGSN – a sister company of WARC – notes in her Spotlight contribution, quoting recent statistics from polling firm Datafolha, “90% of the population still believes in Brazil, despite everything. And that says a lot about Brazilians.

“It's a stereotype, but this time, with a truth in it: creative and restless, there are many Brazilians reinventing themselves in the face of all adversity, making the free time of unemployment an opportunity to learn something new.”

Digital tools power banking revolution

Brazil’s consumers are often eager to adopt new, digital services, as Daniele Lazzarotto of brand consultancy Cordão writes in her article on the introduction of open banking to Brazil.

The instant payment service PIX, which was launched last November by the country’s central bank, is a case in point, as more than 80% of banking Brazilians have already registered their PIX “key”, and it surpassed the country’s wire transfer services in usage within 20 days.

PIX has also become part of wider culture, Lazzarotto argues, as it has “been embraced creatively by Brazilians and inspired new forms of communication, flirting and even memes.”

Even more important, the launch of open banking – which allows third-party applications to give consumers more access and control over their financial accounts – is expected to bring many of the 45 million “unbanked” Brazilians (who don’t use bank accounts) into the financial system, and thus marks a big step forward for the economy, and, in all likelihood, for brands.

Understanding the “Big Brother Brasil” phenomenon

If you want to examine just one phenomenon that exemplifies Brazilian culture right now, it’s a TV show: “Big Brother Brasil” – or “BBB”, as it is commonly known – which first debuted in 2002, and still boasts jaw-dropping popularity that amplifies its cultural, media and marketing scope.

The “Big Brother” franchise might exist all over the world, but it is simply bigger – much bigger – in Brazil. To dip back into comparisons for a moment, as the planning team at agency Talent Marcel notes in its article on Brazilian reality shows, the program “drew 40 million viewers per episode this season, or almost 20% of the population.

“By contrast, the US version of the show brought in 3.8 million viewers during a recent week in July. While that placed it in the top ten most popular US network shows … it reached only 1% of the population.”

But weekly viewership only begins to tell the story of BBB. As Manzar Feres from Globo – the giant Latin American media company that produces the show – notes in her Spotlight article, “Observing the trajectory of a reality show which has been on the air for almost 20 years is a laboratory for studying how marketing and media have changed.”

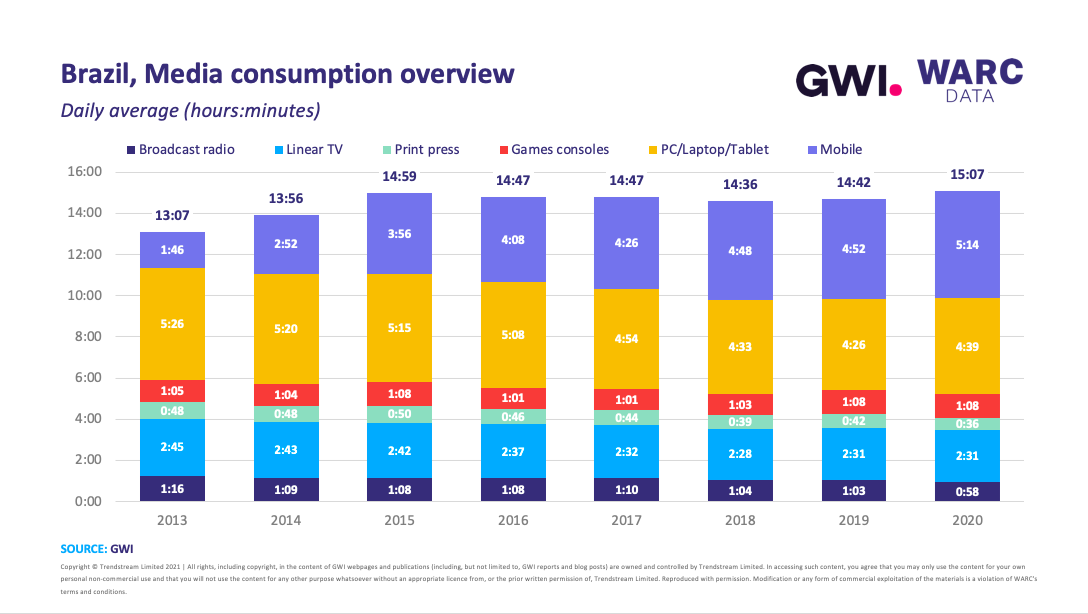

Data from GWI underscores the point. While Brazilians’ usage of most channels has remained relatively stable over the last eight years, mobile usage has exploded, from a daily average of 1 hour, 46 minutes in 2013 to five hours and 14 minutes in 2020; 92% of users say they use a device while watching TV.

The explosion of digital channels has effectively made “Big Brother Brasil” a 24/7, multi-screen phenomenon, with a lot of the action taking place on social media – it had 12.1 billion social impacts this year and spawned 1,000 trending topics worldwide on Twitter.

The show’s contestants take center stage on social platforms, which makes for one of the many fascinating points of interaction between the show and brands.

By way of example, this year’s winner, Juliette Freire, has seen her Instagram following balloon to 31 million and counting, as Luis Dix from Liga Solidária, an NGO, writes in his Spotlight article. And Freire’s newly-signed endorsements with brands like cosmetics giant Avon have made her account an extraordinary reach vehicle.

Globo, too, has effectively leveraged the show’s commercial potential, taking what used to be a pure advertising opportunity into one that fans out to any number of marketing products. And it’s easy to see why this is so appealing: 75% of consumers say that seeing a brand associated with a reality show increases their consideration, a recent study by the company found.

More broadly, Brazilian reality shows have become mirrors held up to the country’s culture, and, to some degree, its social and political polarization. Dix, for instance, notes that a furor erupted during this season of BBB when one contestant – a well-known Black singer – tried to change the show’s narrative to be about Blacks versus whites.

The singer was resoundingly voted off the show by viewers, and lost marketing endorsements. But in a sign that it’s hard to separate the commercial from the cultural, some smaller brands hosted contests the week she was kicked off the show that asked viewers to guess what percentage of voters would reject her.

Brewing up purpose-driven strategies

To focus on frivolous brand interactions, however, would be to miss the crucial role that brands are playing in helping Brazilians through a challenging time.

As Daniel Wakswaser of brewer Ambev notes in this interview, distrust in government is pervasive in Brazil (as is the case in many places elsewhere). Another important dynamic: the same consumers “want companies to be more human companies and to be more purpose-led.”

For Ambev, one response to this situation has been helping local businesses during the pandemic. It piloted an initiative – which later moved through dozens of markets of its parent company, Anheuser-Busch InBev – that provided financial support to restaurants and bars during the worst of the pandemic.

Natura &Co. supports sales reps in new ways

The challenge for cosmetics company Natura &Co. was somewhat different, as Carlos Pitchu explains in this interview, since its Avon and Natura brands rely on legions of entrepreneurs to sell their products, and this community has been hurting during the pandemic.

In response, the organization provided additional digital tools to help them sell virtually, implemented “no touch” delivery, and relaxed the time in which sales reps had to pay their bills back to the company.

Aligning business and societal goals

Marcello Magalhães of brand consultancy SPEAKEASY argues in this story that brands in emerging markets like Brazil need to help people at the most fundamental level by combating food insecurity, a situation that today affects more than half of the Brazilian population as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such initiatives, of course, need to be long term in nature. And Magalhães believes that brands should consider employing a "creating shared values" framework, which aligns business and societal goals, to make this happen.

His hope? That instructive examples from food companies like Knorr and Dole, and also from Ambev, can effectively “shed light on how a consistent and socially-oriented brand purpose can unfold potential paths and roles for brands to combat wicked social challenges such as hunger in Brazil.”

Read more in this Spotlight series

Ambev’s Daniel Wakswaser on how AB InBev shares ideas globally, and the company response to the pandemic in Brazil

Daniel Wakswaser

Natura &Co’s Carlos Pitchu discusses social selling, mission and how the pandemic is changing commerce

Carlos Pitchu

The reality show scene in Brazil is where reality overcomes fiction, and brands are part of the mix

Chimene Demski, Gabriela Soares, Camila Massari, Douglas Nogueira, Hugo Pinheiro, João Guerra, João Pedroso, Laura Diamantstein, and Victoria Aronis

How open banking is creating opportunities for industries, and consumers, in Brazil

Daniele Lazzarotto

A Brazilian perspective on preserving agency-client relationships during a time of turmoil

Graziela Di Giorgi

How brands can help Brazilians over the long-term in dealing with food insecurity

Marcello Magalhães

Brazilian consumers need to be well taken care of during a time of uncertainties

Ligia Paes de Barros