Marketers operate in an alternate reality, Marketingland, where they are far removed from the lives of the people they’re meant to understand and reach. The industry can do better, says Richard Huntington, CSO, Saatchi & Saatchi. He calls for The Marketing Reality Movement, a movement that turns the tide on aspirational marketing, one that better represents and serves the real needs of real people.

This opinion piece is part of WARC’s Future of Strategy 2023 report.

Marketing is in desperate need of a reality check.

For far too long we have allowed ourselves to operate in a marketing metaverse, a digital twin of the real world from which we build our strategies, create our work and plan our campaigns.

This behaviour, while seeming intelligent and effective, is stopping us connecting with reality. And in the final instance it is stopping us doing our jobs properly.

It is time to rebuild our relationship with reality and turn our backs on marketing artifice.

The problem, in part, has its origins in something well understood – the cultural bubble in which we operate. A bubble of experiences and opinions held by a highly educated, metropolitan anchored, relatively young, middle class and white group of people that comprise the majority our industry.

Much has been made of this, particularly by people like Andrew Tenzer through his aptly named consultancy, Burst Your Bubble. Marketing folk don’t look, think, love or live like ordinary people. And few would now challenge the idea that we are not representative of the people that we serve – whether in thought, word or deed.

But this is also true of many other professions that are nonetheless effective. Lawyers seem to do a decent job of representing the interests of ordinary people – whether supporting, defending or prosecuting – without being remotely like them. Same for those running some of our biggest supermarkets, holiday companies, restaurant chains and car brands.

Representation is important for an industry polluted by a monoculture but it’s not the reason for our aversion to reality. After all, empathy has the power to bridge difference until representation becomes more, well, representative.

No, there is something more concerning going on in marketing. It is not simply that we live in a parallel world, we also work in one, something that we might call Marketingland.

Marketingland is an aspirational place, not for consumers but for organisations – a fake world conjured into existence by marketers’ distaste for the real one with all its ugliness, mess and complexity. It’s a place that operates as marketers would have the world, not as it is.

And sadly, far from challenging this, it is the role of research to enable this artifice by serving up just enough reality to make aspirational marketing seem connected to something true and present but not enough to let reality penetrate too far into the machinations of the marketer.

Spend very much time with aspirational marketers and you will start to see the self-deception being practiced. Something that requires a collective form of cognitive dissonance to bridge the divide between a day job that is insulated from the world those marketers then experience when they leave Marketingland at the end of the day.

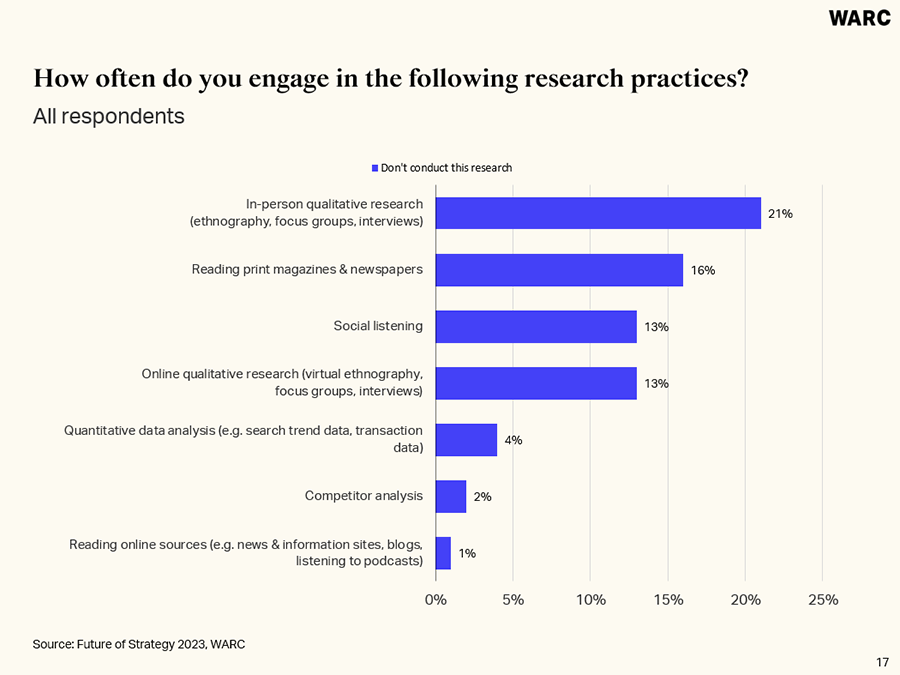

WARC’s Future of Strategy survey suggests strategists are at risk of being distant from real people and culture. The study found in-person qualitative research is the research method least used by strategists (21%).

Three ways marketers build alternate realities

There are many tools being used to achieve this deception, but I want to focus on just three. Three ways marketers, aided by the infrastructure of research, collude to build alternate realities that protect them from what is really happening.

I choose these three because they are the tools I have most tolerated in my career. The ones I have rarely called bullshit upon in day-to-day interactions with other marketers. The ones I have most often gone along with.

1. Narcissism

The first and most fundamental is narcissism. Narcissism protects marketers from hearing or seeing what is going on in people’s lives. Narcissism is not the absence of research input to the marketing process it is about the perversion of its intent.

Much like the beautiful man that can’t help but stare endlessly at his reflection, most research resources are directed towards asking people about brands and categories and not the lives of the people we are trying to serve. We have in a sense inverted the whole purpose of research and the role of marketing to bring the outside into an organisation. We have made it all about us.

Regardless of the methodology, we spend all our time and effort asking people about our brand and competition so that there is no opportunity for people to talk about themselves. We behave like a needy partner endlessly asking ‘do you love me?’, ‘how much do you love me’, ‘do you love them more than me?’ and ‘what would make you love me more?’

Narcissism has made sure that we never really enquire what is going on in real people’s lives.

2. Segmentation

Of course, one response to this focus on the self was segmentation, particularly attitudinal segmentation. This was supposed to capture more of what people really felt or believed in – to seem customer centric.

The idea of understanding exactly who you want to do business with, or more profoundly who you want to build a brand for is one of the great marketing disciplines. It instils focus within an organisation and ultimately should direct product, proposition, service development and indeed the whole customer experience. But the craft of segmentation has long since departed from this simple aim. Indeed segmentation now almost exclusively refers to a particular form of statistical analysis, not the broader aim of deciding who you want to serve and sell to.

And in doing so it has become so complex that its almost now a form of marketing procrastination in which every organisation seems to be eternally waiting for the new segmentation study to be finished – like the protagonists in a Samuel Beckett play.

More fundamentally though, it has also become yet another way to abstract reality, to package it neatly and inoffensively for the aspirational marketer.

Segmentations are not universal but category-specific, as if someone changes identity when they stop thinking about broadband and start shopping for food.

Segmentation studies also insist the population under investigation with all its diversity and complexity can be divided into roughly seven groups of people – maybe fewer, rarely more.

Segmentation practitioners then caricature and demean people by simplifying their lives into crude personas as deep and insightful as characters in a daytime TV drama. Giving them meaningless and offensive labels and then obscuring the whole edifice further by referring to those groups only through acronyms.

And at this point an essential tool for basic marketing discipline becomes little more than a toy with which marketers can pleasure themselves in the privacy of their own offices.

3. Generational marketing

Finally, the end-of-level-boss of segmentation is the stinking edifice of generational marketing. Segmentations may insist that at any one time, people can be divided into neat groups that are completely homogenous while bearing no resemblance to each other. Generational marketing goes further by lumping millions and millions of people together and then ascribing every attitude they hold and behaviour they exhibit to the year that they were born.

While segmentation began with a noble aim, generational marketing is and was always a charlatan’s business. It should be given as much credence in sensible organisations as astrology – an amusing diversion but not the stuff of proper enquiry. And yet we continue to indulge generational marketers and the research companies and consultancies that prop them up.

Gathering everyone on earth born over a couple of decades into a target audience is the final insulation from reality and insult to the real. Because when you do this it is so impossible to represent that group, you can ascribe any value of behaviour expressed by some of them to all of them.

The pursuit of purpose is the poster child for what goes wrong in this situation, the ultimate flowering of aspirational marketing. Marketers wanted their brands to be more important in people’s lives than they were so they invented generations of consumers that they said were predisposed to decide brand choice based on purpose so that they could then cater to that desire. Nothing in this process was real and the result was that marketing debased and discredited the honourable desire to align business with progress.

To my mind, anyone using generational marketing and in particular referring to real young people with letters towards the end of the alphabet should have any responsibility for the future of a brand or business confiscated with immediate effect. As Logan Roy says of his idiot children in Succession, “I love you, but you are not serious people”.

Perhaps this situation has existed for a while. But the progressive collapse of the UK economy and the hollowing out of the middle classes that all businesses ultimately depend upon has made the disparity between Marketingland and the real world more obvious.

The flight from reality in marketing is now so pressing and so problematic that those of us that believe in the real, the observable, the lives that are really lived by the people we serve must take a stand.

The truth may be a relative concept these days, with everyone having their own individual ‘truths’, but real is still objective. And real should be our objective.

The Marketing Reality Movement

So, I am starting the Marketing Reality Movement, and only half in jest. This article is its manifesto, its call to arms and its recruiting station. This is where we turn the tide on aspirational marketing. By making a series of pledges to each other.

Let’s commit a significant proportion of our research budgets – say 20% – to simply understanding peoples’ lives on their terms and not through the lens of our brands and businesses. And not with the intent to change what they think or how they live, not at first anyway. This may be hard to justify in many organisations but I have found that the best return on research comes from broader studies that you can feed off for months to come.

Let’s pledge to get out of the viewing facility. They exist for our ease and edification turning research into a sport and our customers into laboratory subjects. All research has context and so should be undertaken on a customer’s territory and not ours. This doesn’t always mean in home but its extraordinary what you learn when you are inside people’s lives looking out rather than on the outside peering in.

Let’s go broad or go deep and not mess about in the middle. In other words, we should be using vast data sets of, ideally, behavioural data to understand the landscape of people’s lives in aggregate. Taking in whole horizons, mountains and valleys. Or we should be up close and personal talking to people in depth and at length about their individual experiences. No more ‘nationally representative samples of 1002 adults’.

And when we get personal let’s talk about real people and their stories. Rather than synthesise the lot of them into a fictitious default customer, we should be celebrating their individual lives as distinct from each other. I would rather know one thing about one person that is real than a whole load of nonsense about lots of people that has been liquidised into the insight equivalent of baby food.

And above all else, let’s commit ourselves to love and respect the people we serve. No matter their lives and their views. No more disrespectful personas and segment names and above all no more acronyms. Everyone is trying in their own way to be a good person living a good life. Let’s treat them that way.

And no more generational marketing.

See this as an attempt, before it’s too late, to bring reality back to marketing or perhaps bring marketing back to its senses. A movement – the Marketing Reality Movement – for those that really care about people and truly connecting with them as human beings. A commitment to put people first again.

What is the point of marketing if it is not to represent the lives of real people and then work out how best to serve them?

Not in Maketingland but in the real world.