Purpose Incorporated: A primer for brands in APAC

This article is part of a special series on how brands in APAC can go beyond profit to do good and do better for themselves and others. Read more.

Non-WARC subscribers can read this series in its entirety by accessing the articles via the landing page.

Why it matters

While China may view diversity and inclusion as a Western concept, the growing trend of female empowerment is favouring more inclusive representations of women but Western brands should still consider local cultural traits before launching DEI campaigns amid rising national pride and conservatism.

Takeaways

- DEI is antagonistic to the idea of a united and harmonious Chinese society, where an individual is part of a group.

- Chinese audiences expect to see more Chinese represented in Western brands’ communications locally and globally.

- Western fashion brands are pioneers in representing black women but Asian women have been under-represented in ads.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement accelerated companies’ concern about diversity and inclusion. The major challenge for global brands today is to consider a country’s specific cultural and societal context around diversity and roll out locally relevant initiatives.

In the United States, the history of slavery, persistent systemic racism and the growing mosaic of ethnic minorities have placed the topic of “race” at the core of societal debates. American companies pioneered DEI (diversity, equality and inclusion) policies and still lead the trend. Yet, more brands fall into the trap of “cultural appropriation” and face the risk of getting “cancelled”.

In European countries like France, the United Kingdom, Spain, Germany or Italy, where immigration and/or the history of colonisation led to racial discrimination, diversity is also a core societal concern, even if brands are less pressured to communicate in a more inclusive way.

On the contrary, China is a mono-racial country, with 92% of the population identifying as Han (although it counts around 56 ethnic minorities) and where the proportion of non-Asian foreigners is insignificant (the United Nations estimated that China has the fewest number of foreign-born residents at only 0.07%).

From the Chinese perspective, diversity and inclusion is a concept imported from the West and appears to many like a buzzword. Historically, it is antagonistic to the founding idea of a united and harmonious Chinese society, where an individual is conceived as part of a group – a married couple, a family, a community, a country. China remains a collectivist Confucian society, where the concept of unity prevails over diversity, which is suspected to lead to separatism. Unsurprisingly, the #BLM movement had little impact on China. With the COVID-19 crisis, the Chinese have been more concerned about rising anti-Chinese racism and China-bashing abroad.

Racial diversity in China first refers to the dichotomy between Asians and Caucasians. Despite the growing representation of black models in fashion shows, black, Arab or Latino models are rarely seen in advertisements. Few Western brands feature black models. Sports brand Nike, whose global communication massively represents black people, mostly features Chinese people in China, with few exceptions such as black sports celebrities highly popular locally, for example, LeBron James or Michael Jordan.

With the rise of national pride – fueled by China’s successful management of the COVID-19 crisis and its growing economic ascension – the main expectation of the Chinese audience is to see more Chinese people represented in Western brands’ communications locally and globally.

While Western fashion brands have been pioneers in their representation of black women, Asian women were until recently under-represented in fashion shows as well as advertising campaigns. Today, the representation of Asian models and celebrities is growing – in fashion shows, among brand ambassadors, in advertising campaigns and magazine covers. In fashion magazine Elle China, 14 out of the 17 celebrities on the cover were Chinese in 2020. In comparison, Japanese people remain more attached to foreign celebrities and models.

Western luxury brands were reluctant for a long time to get local ambassadors, as they feared “diluting” their European heritage. They were lagging behind mass market brands regarding diversity and inclusivity. Yet, with the growing importance of the Chinese market for the industry (China will account for 40% of global luxury sales by 2025, according to McKinsey & Co’s China luxury report), luxury brands are more overtly localising their communications.

Over 30 luxury brands now have had local ambassadors in China, a trend which keeps accelerating. A recent luxury communication trend is to appoint Asian celebrities – notably K-pop idols – as global brand ambassadors. These celebrities benefit from incomparable levels of awareness locally and carry strong influence among millions of younger millennial and Gen Z consumers.

Blackpink’s Jisoo (top), Dior fashion and beauty ambassador since March 2021, and K-pop star HyunA, Loewe ambassador since July 2021

Western brands’ inclusive campaigns don’t seem to “resonate” with the Chinese audience. Calvin Klein’s Pride campaign in June 2020, featuring black, overweight, lesbian trans model Jari Jones, stimulated some positive comments on Weibo from Chinese women but only because they saw the advertisement as breaking from traditional beauty conventions. Their understanding of this campaign was feminist, not racial or pro-LGBT.

Following the #BLM movement, the decision by beauty group L’Oréal to eliminate the word “whitening” and the expression “fair and lovely” from product catalogues was misinterpreted in China and generated negative comments on social media.

Chinese consumers did not consider the association of white with beautiful skin as racist, since fair skin has been a beauty criterion in China for centuries. On social media, Chinese women expressed their wish to be allowed to consider white skin as beautiful, the same way as Western women aspire to tanned skin, without being considered as racist.

Also, Victoria’s Secret’s recent campaign featuring Yang Tianzhen, a plus-size Chinese entrepreneur advocating body positivity, received negative comments. To Chinese women, she was not considered a match for the Victoria’s Secret style and was non-aspirational from a Chinese beauty standpoint because historically, the ideal of feminine beauty is extremely standardised in China.

Victoria’s Secret “Be Yourself” campaign, 2021

Chinese brands seem to better resonate emotionally via inclusive campaigns promoting female empowerment while challenging beauty norms.

The Chinese underwear brand Neiwei’s “No body is Nobody” campaign (2020) – featuring six women with “flaws” (scars, grey hair, muffin tops) that would be considered mainstream in the US – was unprecedented in China, where representations of women in the media are rarely realistic.

Yet, interestingly, Western brands attempting to represent non-conventional Chinese beauties have faced backlash. Zara’s “Beauty is Here” campaign in 2019, featuring Chinese model Jing Wen with her freckles, attracted hundreds of millions of views for #zarauglifylingchina because in China, beauty is linked to health and a core beauty criterion is flawless skin. The campaign by a Western brand was perceived as disrespectful towards China, even more so when the Chinese model was posing next to a Caucasian model with flawless skin.

Besides inclusive beauty, ageing women and the alienating warning to them to stay (keep looking) young spark growing discussions on social media. In China, significantly more than in the West, women between 40 and 50 years old are almost invisible in the media.

Yet, the massive popularity of the reality TV singing and dancing contest show in China “Sisters who make waves” in 2020, featuring women aged 30-50+, all confident, talented and beautiful, initiated a societal debate around middle-aged women and encouraged brands to increase their visibility.

Following the show, Guerlain appointed 48-year-old brand ambassador Ning Jing and Bottega Veneta featured Yu Feihong, 50-year-old single actress in its SS 2020 collection but with authentic signs of ageing like wrinkles or grey hair always concealed. The aspirational driver for brands is to represent older women as looking 20 years younger.

Guerlain ambassador Ning Jing, 48 (top) and Yu Feihong, 50, model for Bottega Veneta

Regarding the young generation, gender representations are crystallising the need to shake up norms and societal injunctions in China. The massive popularity of androgynous celebrity singers embodies the audacious exhortation to “be yourself”.

Playing with gender is considered an expression of individual freedom in a country where censorship, family and societal constraints remain oppressive. Many tomboy-looking hip hop and K-pop singers with short hair and tattoos, like Liu Yuxin or Danny Lee, are highly aspirational to Chinese women and widely used as ambassadors by Western brands.

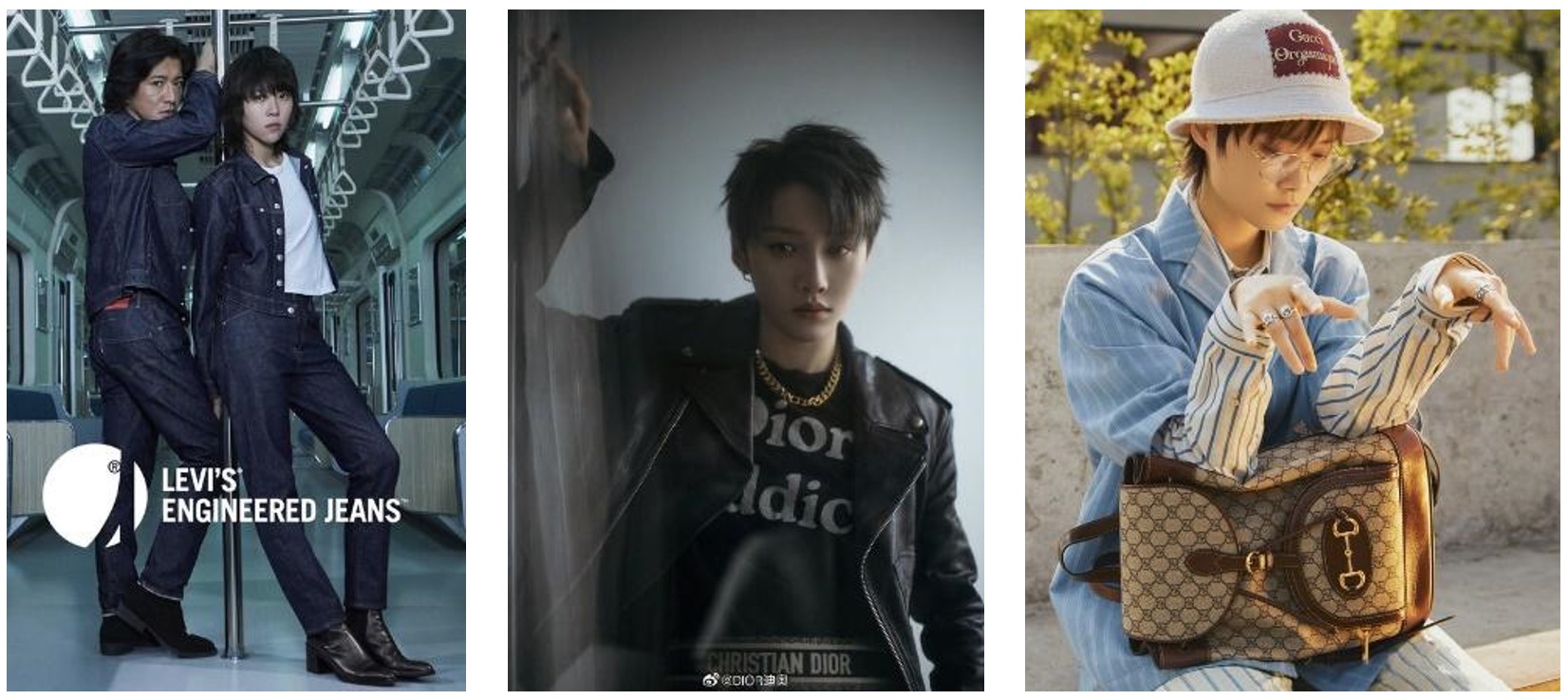

Levi’s ambassador Leah Dou, 2019 (left), Gucci ambassador Chris Lee, 2020 (centre), and Dior’s “best friend” Liu Yuxin, 2020

Yet, the representation of gender-neutral men – Little Fresh Meat, androgynous pre-pubescent looking men influenced by the Korean “flower boys” – is now fading due to growing censorship on effeminate men (in August 2021, China's broadcasting regulator said it would ban "effeminate" and ”abnormal” aesthetics considered "unhealthy”, notably among male celebrities wearing make-up).

Regarding LGBTQ+ representations, there seems to be a gray area. The 2020 Chinese New Year ad campaign by e-commerce platform Alibaba, where a young man brings his boyfriend home for the annual family reunion dinner, raised a considerable number of positive comments on social media.

In socially conservative China, where homosexuality is still banned in films and where the Chinese government recently promoted more sports at school to “prevent the feminisation of male adolescents”, inclusive LGBTQ+ ads seem to be welcomed by the younger generation.

Cartier Trinity ring campaign, 2020

Yet, ambiguous campaigns are rejected. The commercial for the Cartier Trinity ring, presenting couples of men and women as family or friends, was considered “disturbing” and “stigmatising” on social media.

Western brands tend to oscillate between two extremes: they either have a cosmetic approach to LGBTQ+ issues, with inclusive, institutional messages, or have strong, daring statements like Dior’s appointment of Chinese transsexual icon Jin Xing as ambassador. This choice, although well received in China because of Jin’s popularity, was rather dangerous.

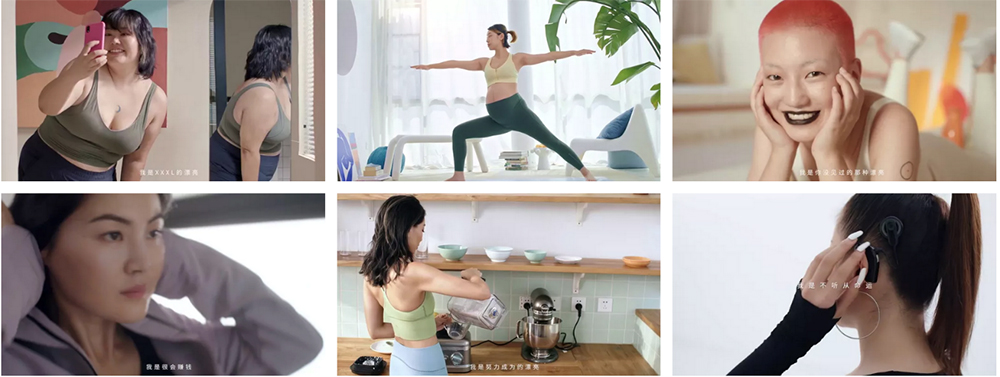

A successful strategy is often to leverage on LGBTQ+ to address wider women’s issues. For instance, Chinese activewear brand MAIA ACTIVE, launched its Spring 2021 campaign on International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia & Transphobia. The campaign portrayed five women, including a transgender woman, rejecting beauty stereotypes.

Local brands often address LGBTQ+ issues in a more emotional and authentic way, notably through the topic of family rejection and reconciliation.

Many gay advertisements depict empowering freedom but also the difficulty to live the life chosen. They rely on similar emotional drivers than campaigns and TV series focusing on single women striving to be independent, despite familial and social exhortations to get married. Focusing on authentic life stories, they make these campaigns more emotional.

An advertising campaign for Chinese phone brand Meizu features the testimony of a mother who accepts her young gay son. She relates the case of another gay boy who committed suicide and invites parents to be more tolerant. This reconciliation with the family is a happy ending and a powerful emotional driver for all Chinese people.

On the topic of diversity and inclusion, China is still lagging behind the US. Yet, the representations of diversity are evolving fast and the trend of female empowerment is favouring more inclusive representations of women.

In the context of rising national pride and conservatism in China, Western brands should take into account local cultural traits before launching DEI campaigns locally.