Creating cultural advantage

This article is part of a series of articles from the WARC Guide to creating cultural advantage. Read more

Why it matters

Cross-cultural communication should not be limited to language and ought to begin with cultural integration in the organisational structure, product innovation and supply chain for overseas markets, so that brands venturing into new territories can achieve brand strength.

Takeaways

- Avoid the “curse of knowledge” trap – the cognitive bias that each person has due to different life experiences and environments.

- Communication is a double-edged sword – not only can it magnify a product’s shortcomings, but it can also enhance its strengths.

- During localisation, the premise of cultural integration is to respect local sentiments, rather than blindly chasing trends.

“Language is just a tool; what’s more important is learning about unfamiliar cultures and histories, the humanities and life in other countries.”

I came across this comment in my WeChat Moments. For someone like me who has been in Singapore for almost a year after relocating from China, this statement resonates deeply.

In October 2022, I arrived in Singapore to begin a new chapter in my life. Before that, I had spent 10 years living and working in Shanghai, where I was responsible for brand communication for multinational corporations entering China. In Singapore, I took charge of the RF Thunder Singapore office, marking RF Thunder’s first step into Southeast Asia. The communication organisation I’m a part of is an example of a Chinese brand going global, one of 700,000 such companies that have ventured abroad, with over half of them emerging during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2022, China’s Communist Party stated in its 20th Congress report: “Persist in high-level opening up and accelerate the formation of a new development pattern in which the domestic and international circulations reinforce each other with the domestic cycle as the mainstay.”

With a series of supportive policies, 2023 has been defined as the year for Chinese brands to comprehensively go global.

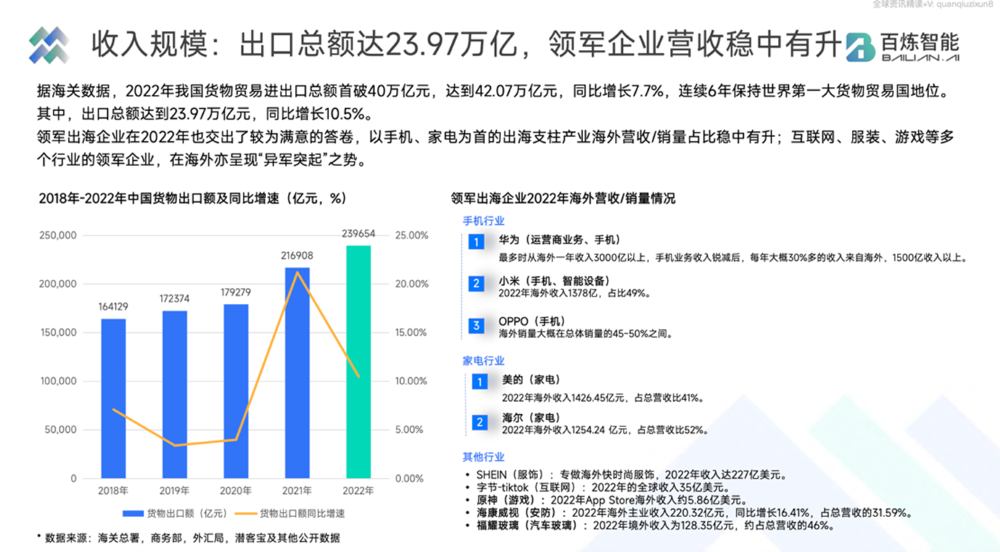

The overall number of Chinese brands going global is almost explosive. According to customs data, China’s total import and export of goods in 2022 reached 42.07tn yuan and the scale of cross-border e-commerce exports in 2025 is expected to be 2.66tn yuan. Nearly all sectors, from culture and entertainment to information technology, are set to experience a compound annual growth rate of over 20%. Leading industries spearheading globalisation efforts, such as smartphones (Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo) and home appliances (Midea, Haier), are also seeing stable overseas revenues, with approximately 30–50% of their income coming from abroad each year.

Currently, a significant percentage of Chinese companies are in the initial stages of globalisation, and it takes three to five years to transition from product globalisation to brand globalisation. In other words, the next five years will see a significant increase in the demand for brand building and communication capabilities from Chinese companies and their agencies.

But at present, there are very few agencies capable of handling this type of work. In the past year, I have encountered two main types of competitors:

- Purely local (such as purely Singaporean talent) teams, where proposal-writing skills and understanding of client briefs deviate significantly.

- Teams based in mainland China, which have experience serving Chinese clients and language abilities to interface with overseas markets but have limited cultural and consumer insights into overseas markets beyond what can be found in reports and search engines.

Therefore, having a team structure that combines “Chinese people + locals” and the flexibility to make real-time adjustments are crucial in any globalisation process.

The second observation I had was around “cultural shock” that different China-outbound brands had when it comes to the execution of communication campaigns. Many Chinese brands in the process of going global tend to have a vague segmentation of overseas markets, thinking that regions such as Southeast Asia, South America, South Africa and the Middle East are a single entity (perhaps on a map, the land area of these markets does not look as large in China and the US). In reality, each of these regions is composed of a dozen or even dozens of countries, with their own races, cultures, lifestyles, topography and economic conditions.

Recently, we received a brief that required our team to partner with fashion media publications in Southeast Asia. This is relatively easy to accomplish in China, where one will communicate with a single point of contact at Vogue or Elle to cover the entire mainland market for content collaborations. This POC can also help brand clients launch activities in different cities and engage with consumers on a nationwide basis. However, in Southeast Asia, it’s not as simple as making a single phone call or contacting one person. If a brand wants to collaborate with Vogue or Elle in countries like Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines, it needs to reach out to the companies that distribute the magazines in these three countries. The human resources required for this are several times larger than those needed for media collaborations within China.

So how can we create mutual cultural understanding for Chinese brands and their overseas partners in the process of going global? Clearly, copying the approach that international brands used to enter China is not suitable because China itself is an insular market and when Chinese brands enter another insular market, they should go through these steps:

- The first step involves extracting a globally unified brand positioning and product strategy from the domestically successful business model and communication experience of existing products and brands in China.

- The second step involves executing a customised local execution plan based on this positioning and strategy (which often requires adjustments compared to the domestic strategy) when landing in different overseas markets.

Whether it’s a Chinese company going global or the localisation of an international brand in a particular market, the following two takeaways apply:

1. Avoid the “curse of knowledge” trap

Rushing cultural exports or trying to please local consumers can be a dangerous operation. In communication theory, there is a concept called the “curse of knowledge”, which refers to the cognitive bias that can arise because each person has different life experiences and environments. The main way to reduce this cognitive bias is through “self-disclosure” and “seeking feedback”.

Going back to communication theory, this means revealing the strong core values within your own brand culture and genes to local consumers (but not in an instructional manner). At the same time, observe native consumers and receive feedback through interactions with them, focusing on their cultural and social concerns. This can help local consumers better understand you and break the curse of knowledge.

2. Communication is not only the icing on the cake

Good products will “sell themselves”, of course. In addition to reaching more people and increasing the desire to try the product, innovative communication can also create demand in the early stages of conversion. Therefore, brands need to make some small communication attempts in the local market first, according to the interests of local consumers, and then adjust the product strategy. Communication is a double-edged sword – it not only magnifies the shortcomings of the product but also serves to enhance the strengths of the product.

How to excel in cross-cultural communication

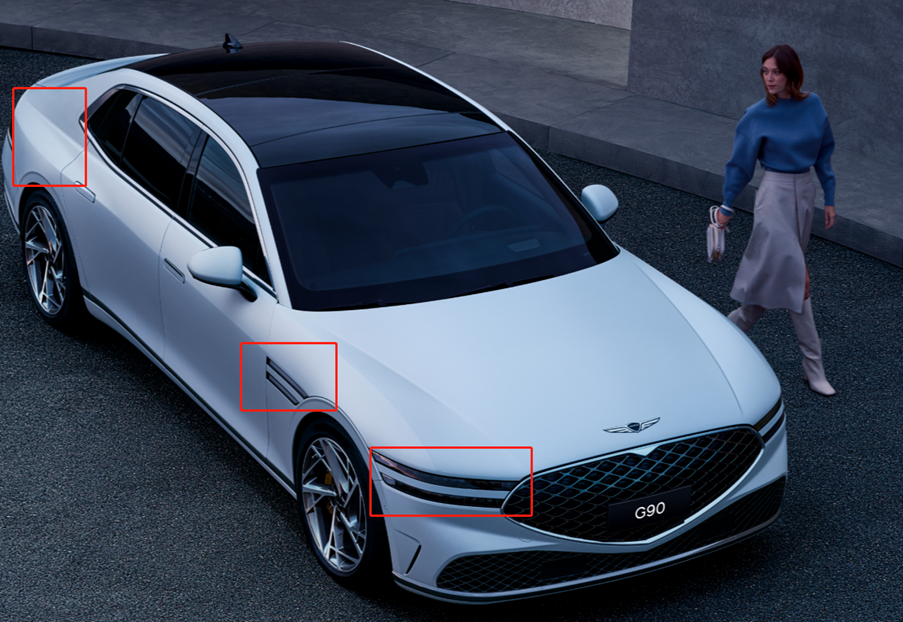

Case study 1: Genesis’ transformation of the 'Two Line' Architecture design language in China

As the South Korean Hyundai Group’s luxury car brand, Genesis entered the Chinese market in April 2021, several years later after its entry into markets like North America (2016). Thus, before entering China, Genesis already had an established, unified official English design language.

In China, it faced the challenge of translating Chinese copywriting while retaining the original English meaning, showcasing its unique features, avoiding content emphasised by other luxury brands and yet considering Chinese traditional culture.

Genesis has a classic car body design language called the 'Two Line' Architecture, defining the horizontal dual-line side structure of every vehicle, starting from the LED headlights, extending along the turn signals and body contours to the tail lights, to showcase the Twin Parallels design concept.

When translating this concept for the Chinese market, the Genesis team referred to the Chinese classical literature’s interpretation of Two Lines and Twin Parallels. In one of the Four Books of Chinese philosophy, the “Doctrine of the Mean” states that “all things are nourished together without their harming one another; the courses of the seasons and of the sun and moon are pursued without any collision among them”.

This translation not only speaks to harmonious lines but also encapsulates Genesis’ design of “dynamic elegance”, where the essence is the fusion of dynamic design and elegant lines, running in parallel without contradiction.

The Genesis marque’s Two Lines architecture

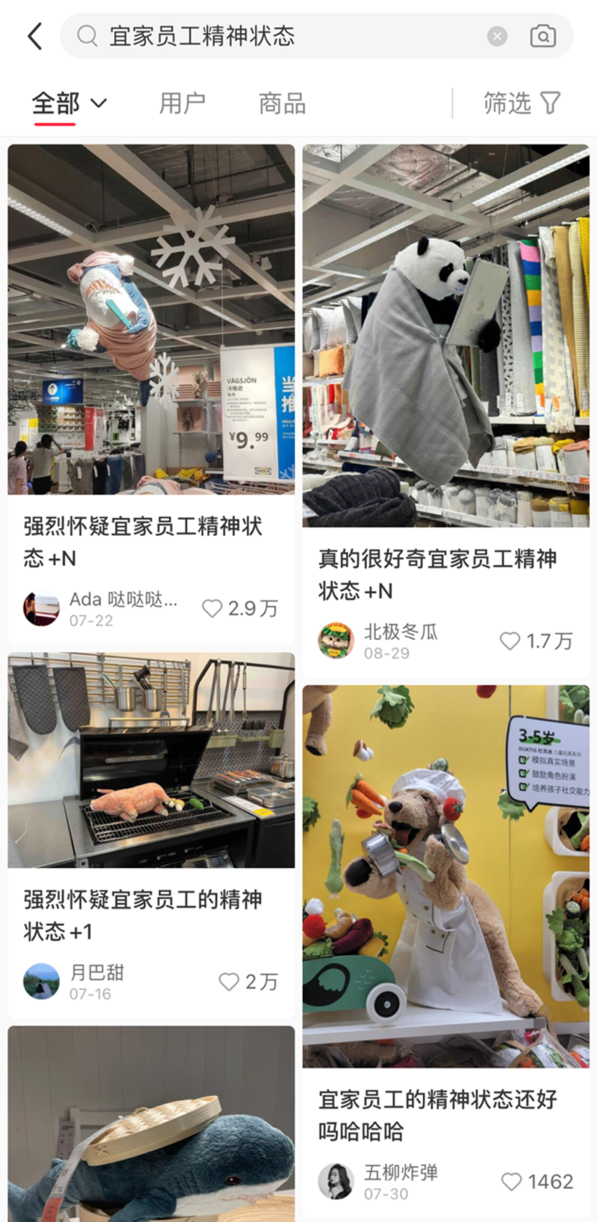

Case study 2: IKEA’s display of nine provincial dialects in Chinese stores

Swedish furniture retail brand IKEA gained popularity on Chinese social media for its in-store displays using clever communication materials. The brand savvily used various Chinese regional dialects and even culinary characteristics to introduce its products, creating localised content that resonated with local consumers eager to share their reactions. For example:

“No drilling, easy to install on the wall” was expressed in Shaanxi dialect to mean “beautiful”

Interior of Chinese IKEA store

Various social media posts of strange IKEA retail displays

Of course, when pursuing localisation and tapping into trending topics, there are inevitably missteps along the way. For example, a reference to “Three Children” caused discomfort among some Shanghai netizens. Therefore, the premise of cultural integration is to respect local sentiments, rather than blindly chasing trends. (China’s third child policy is particularly contentious in cities like Shanghai, where there are concerns about the high cost of living, work-life balance, gender inequality, housing constraints and potential adverse effects on women’s careers.)

IKEA sign referencing three children

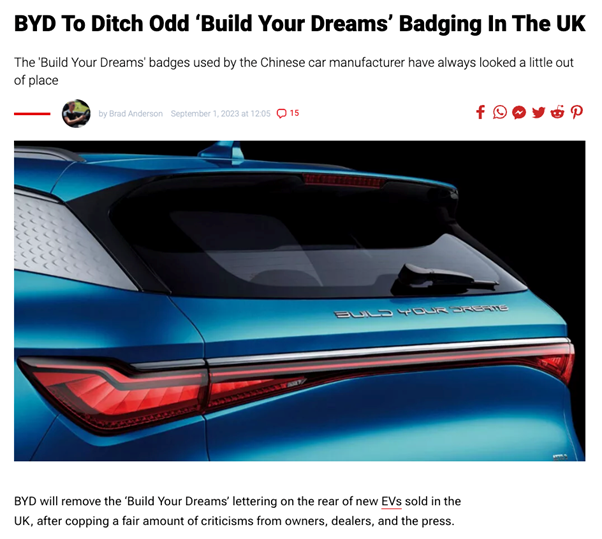

Case study 3: BYD’s “Build Your Dreams” badging needs renaming for overseas markets

When BYD entered the European market, its faced complaints from vehicle owners due to its “Build Your Dreams” badge. While this tagline was well-received in China with the aspirational emphasis on hard work, ambition and the pursuit of success, European consumers preferred to chill out and “Build Your Holiday” instead.

In response, BYD removed the lettering on the rear of new EVs sold in the UK. It also renamed car models meant for overseas markets, such as the “元PLUS” SUV model from the BYD Dynasty series, and opted for the name “Atto”, instead of using direct transliterations like “Tang” and “Han”. BYD did not provide an official explanation for this, although some speculative analyses suggest that the name “元朝” (Yuan Dynasty) might evoke associations with Genghis Khan for European audiences.

Atto was derived from the term Attosecond in physics and not only represents speed but also plays on the phonetic similarity with the original “元” (Yuan), acknowledging the Chinese market’s interpretation of the character.

Case study 4: McDonald’s Big Fry Day in China invites fans to “beat the heat with fries”

Since 2015, McDonald’s China has cleverly turned a fixed solar occasion into a localised special marketing event known as “McDonald’s Big Fry Day” by playing on the phonetic similarity between “Big Fries” and the traditional Chinese solar term “Da Shu”, which means “major heat” that takes place around July when all parts of China experience their highest temperatures and the greatest amount of rainfall. Each year, McDonald’s China introduces a series of promotions, inviting customers and friends to enjoy fries while beating the heat during one of the hottest days of the year.

In addition to the phonetic wordplay, McDonald’s capitalises on the Chinese tradition of seeking relief from the summer heat. It combined fries with other menu items to create “cooling meal deals”, generating more opportunities for customer engagement and purchases.

Furthermore, in recent years, McDonald’s Big Fry Day has increasingly focused on summer outdoor activities like shopping and camping. It continuously introduces interesting peripheral merchandise and collaborates with local Chinese design brands to create more buzz, enhancing its brand visibility and favourability.

For example, the Fries with your Chums campaign uses the term “chums” (which means “friends” in its original sense) to cleverly convey the inseparable connection between fries and friends.

McDonald’s poster of two friends

If you search for worldwide McDonald’s marketing activities in July, you will find that “Big Fry Day” (July 22–24) coincides with International French Fry Day celebrations in other markets (July 13), known as “National French Fry Day” in the US and the UK. Although there is no official confirmation that “National/International French Fry Day” and China’s “Big Fry Day” share the same origins, we can speculate that the Chinese edition is an innovative attempt by McDonald’s, tailored for the Chinese mainland market.

Case study 5: Starbucks localises in relatively closed Korean market

In just a decade, South Korea has emerged as the world’s third-largest coffee market. Coffee houses, shops and cafes are highly popular among South Korean consumers and there is a plethora of local coffee chain brands, leading to fierce competition. According to a survey conducted by the National Consumer Committee of South Korea in November 2022, South Korean residents spend an average of US$75 per month on coffee.

Due to the prevalence of the Korean language, South Korea’s market is generally considered relatively closed. While South Korea has always had an open attitude towards Western culture, Western brands still face cultural and language barriers, making it challenging for them to enter this market smoothly. But Starbucks, as an international brand, has successfully established a strong presence in South Korea.

It achieved this by positioning itself as a fashionable, high-end coffee chain brand leading the culture of “takeaway” coffee. This positioning extended to popular culture, where scenes of K-pop idols drinking Starbucks iced Americano coffee often appear in live broadcasts and Korean dramas. Through this soft product placement, Starbucks aimed for top-of-mind awareness and influenced Korean fans to choose Starbucks, further enhancing its brand equity.

Starbucks has also introduced localised products, such as seasonal beverages themed around cherry blossoms and yuzu, flavours that South Koreans are already very familiar with. In addition, some Starbucks stores have undertaken customised interior and exterior designs inspired by traditional Korean houses, known as hanok.

Starbucks store surrounded by picturesque scenery

Case study 6: Vivo (RF Thunder client) leverages colour, culture and fashion flexibly in and outside China

In recent years, Vivo has excelled in “colour marketing” among smartphone manufacturers. Its S16 model, featuring a colour described as 颜如玉 and resembling jade, is a low-saturation hue between white and light green, and dominated Chinese social media platform Little Red Book’s newsfeed in end-2022. This term is derived from ancient Chinese poetry and signifies a beautiful and youthful appearance. (颜如玉 originates from the 12th poem in the Nineteen Old Poems collection. It is often used to refer to a young and beautiful woman, with the most famous reference being the line from Song Dynasty poet Zhao Heng’s poem: “In books, there are golden houses; in books, there are faces as beautiful as jade”.)

When Vivo introduced the overseas model of S16, which is V27, in Southeast Asia, it used a similar green colour. However, the original colour theme wasn’t continued in its marketing, with the reason being that Southeast Asia’s consumer environment, where Chinese culture is not dominant, and the word “jade” lacks strong local resonance.

Subsequently, Vivo’s marketing approach in Southeast Asia turned away from colour to address the challenge of how its product’s existing high-end image wasn’t a significant advantage compared to competitors. It collaborated with top fashion magazines in key Southeast Asian markets to position its green V27 smartphone as a “fashion statement”.

The brand also launched a similar green model in the Vivo Y series in Southeast Asia but also avoided replicating the domestic colour-marketing strategy. Instead, it localised marketing efforts by focusing on memorable and relatable stunts. For instance, in Malaysia, it introduced the Vivo Y36 5G Semporna Green smartphone, which inspired a limited edition “Semporna Green Avocado” beverage from Liho Tea.

Marketing campaigns for this smartphone, including print ads and videos, ranked first in engagement on Facebook in Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines. This communication approach effectively built brand awareness and generated significant social media buzz across these three markets.

Conclusion

From the case studies above, regardless of transcreation or hyperlocalisation, which are just different names with similar principles, cross-cultural communication should not be limited to language alone.

It should begin with cultural integration in organisational structure, product innovation and supply chain layout for overseas markets, adapting to local conditions at all times.

Returning to the reason for my move to Singapore, for Chinese businesses going global, the golden period for brand building lies in the next five to 10 years. For brands and overseas agencies venturing into new territories, these are crucial years of transitioning from chaos to order, as well as accumulating brand strength.

As long as we persevere, we will mature in our communication methodologies and gain valuable experience to make China’s quality brands successful around the world.

Sources

艾媒咨询 | 2023-2024年中国企业出海发展研究白皮书

https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/95587.html宜家本土化营销,太不着边了!

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/438YcZ0ac-ooGDs5ZjA9DA

麦当劳中国大薯日官方介绍页 official page of Big Fry Day: https://www.mcdonalds.com.cn/index/mcd/branding-3/bigfry

https://uk.news.yahoo.com/mcdonald-giving-away-free-fries-164954573.html

https://mcdonaldsblog.in/2023/07/happy-international-fries-day-to-all-the-fries-lovers/

https://globalmarketingprofessor.com/starbucks-in-korea/

https://www.greenqueen.com.hk/amp/starbucks-korea-plant-based-food/

https://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=104002

Read more articles from the WARC Guide to creating cultural advantage.

Developing ‘CQ’: Why cultural intelligence is required to create effective work

Wendy Siew

EssenceMediacom

Culture 3.0: A new paradigm for brands to engage with communities

Amber Haank and team

Amaru

Understanding the double-edged sword of culture and polarisation

Paola van Cappellen

Creative Culture

Going glocal: Why modern brand marketing is like a symphonic orchestra

Dominique Touchaud

Shokunin Marketing

Moving beyond ‘just enough’: How to sense check your cultural strategy

Jenn Chin

Uncommon Kind

Cross-cultural communication: Transcreation is no longer just about language

Phoebe Shen and team

RF Thunder SG

‘Being operationally fit’: LUX on leveraging underlooked areas of cultural advantage

Swarnim Bharadwaj

Unilever

Why Southeast Asian brands are primed to take on global growth

Adji Saputro

Kantar

Global brands in local contexts: Are they working as well as they used to?

Alex Haigh

Brand Finance

How Asia is becoming an exporter of global culture

Acacia Leroy

Culture Group

Cultural hybridity: The future of branding

Laurence Lim

Cherry Blossoms Intercultural Branding

Cracking the code of consumer motivation in an age of reverse glocalisation

Victoria Hoyle and Virginia Alvarez

Wunderman Thompson

Navigating a heightened political climate: How US companies must sharpen social issues engagement strategy

Andrea Hagelgans and Ebony Brown

Edelman

Navigating business, culture and politics: How brands can connect with consumers

Nick Hope

Edelman UK

Walk this way: How to engage in culture in a meaningful way

Marcus Collins

University of Michigan