Amidst recent greenwashing crackdowns and the rise of greenhushing in Australia, WARC Asia Editor Rica Facundo examines in this Spotlight Australia series why “perfect is the enemy of the good” in a brand’s sustainability journey.

This article is part of a Spotlight series on sustainability in Australia. Read more

Addressing the sustainability challenge in marketing is an existential conundrum.

Many of the sustainability talks I attend and experts I speak to always preface the conflicting goals of marketing and sustainability. On the one hand, marketing exists to drive growth by encouraging consumption, while sustainability is about preserving our resources for the betterment of the planet and its inhabitants.

The controversy around the recently launched “Mother Nature” Apple advertisement epitomises this quandary. While advocates commend the ad’s ability to convey a complex sustainability message to the broader public, one analysis pointed out that this came off the back of the release of four new iPhone models and that their “ad for their climate commitments is also an ad for their new products”.

The solution lies in the messy middle and requires reorienting how marketers view growth and deliver value to its customers. This is by no means an easy feat. However, the industry is rife with a sense that brands are not doing enough and at speed, especially with regulations catching up and greenhushing creating an unproductive environment of fear.

This is a global problem but is keenly felt in Australia as greenwashing scrutiny swells. In a survey conducted earlier this year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) discovered that 57% of businesses had promoted “concerning claims about their environmental credentials”.

Most recently, the Australian government was called out in an open letter published in a full-page New York Times ad by the scientific research body The Australian Institute.

While the fear of backlash is understandable, it’s also unproductive given that this crisis requires brands to be open and transparent so that the industry can speed up development. In this instance, the sentiment that “perfect is the enemy of good” is the problem we’re trying to address in this spotlight and exemplifies where we need to move away from by highlighting what’s working and required to really drive sustainable value.

Sustainability is only one source of value creation

Over the years, campaigns about sustainability always lead with green claims, which is unsurprising given the various data points that show Australian consumers becoming more sustainability-focused.

However, while sustainability is a source of value creation, our contributors agree that brands should not forget that it’s not the only reason why consumers buy. Instead, various USPs should go hand-in-hand.

Ogilvy’s Toby Harrison also points out these contradictions: “Despite the fact that Australians see sustainable goods and services as ‘worth paying a premium for’, the reality is that most of us actually need something more,” such as if there was “considerable benefit to them (eg, saving money) or if they had to comply due to government and corporate interventions such as recycling or using reusable shopping bags”.

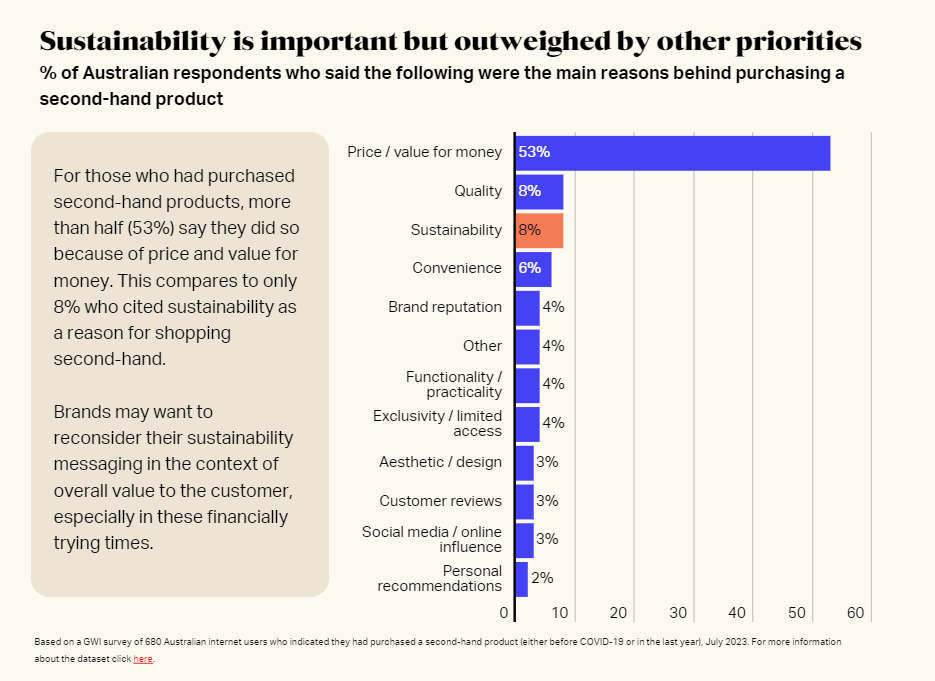

Our Spotlight infographic also highlights this discrepancy in the usual sustainability-oriented narrative of the second-hand market. The main motivation for those who had purchased second-hand products is actually price and value for money (53%), with sustainability coming in second place (8%), together with quality.

For recycled eyewear brand Good Citizens, pricing was a huge consideration for the company.

Founder Nik Robinson said, “When we priced it at $99, people had this perception they were bad quality because they were cheap. So we changed the lenses and redesigned the glasses. We don’t want pity buys, we want people to buy the product because it looks good. We have to also win it in the style game.”

From mindless to conscious consumption

In a world where marketing and sustainability need to co-exist, one of the biggest challenges for brands is to move away from a mindless consumerism model to encouraging more conscious consumption that puts quality and value at the heart of the product.

We first featured this theme in our Southeast Asia spotlight last year but our Australia spotlight outlines more ways to achieve it.

Our contributors agree that this is rich territory for brands to deploy the power of creativity, design and storytelling to help shift behaviours and mindsets.

SGK’s Phil Hwang writes, ”Regardless of way-in, design is pivotal in generating consumer desirability that not only makes the product a ‘proud choice’ instead of a ‘sacrifice’, but lets the brand reap the competitive advantages of its actions, thereby rewarding better players and making sustainable actions sustainable commercially as well.”

Our two featured local brands in this spotlight are great case studies of how to change the consumer’s relationship with products and change the codes of the category.

Despite some initial skepticism from experts, Robinson spoke about how a self-repair USP is a way for consumers to form a bond with the product and brand.

“We had some clever marketing friends who told us that we shouldn’t talk about the repairability USP because that puts in people’s minds that it’s going to break. But I don’t think that’s true. Imagine buying a car and thinking that you will never have to get it repaired. If cars are repairable, why can't glasses be?”

Another example is from recycled toilet paper brand Who Gives A Crap, which stands out with its unique personality, colourful designs and toilet humour. Maria Chilewicz, head of of brand management, shared that when used together with its sustainability credentials, it becomes an effective behaviour change strategy.

“While the toilet paper category seems to lean heavier on cuteness to communicate softness, as well as serious eco messaging, we do the opposite by tapping into humour to address the topic at hand and therefore defy category conventions.”

Delivering impact through system thinking

Transforming brands into a force for good is not just a communications problem. White Grey’s Lee Simpson points out that the conversation has now moved to looking at your business and the context it operates in as a system. “This is a more holistic view that has an appreciation of the interconnectedness of elements in real-world systems – business, government, technology, finance and, of course, the planet.”

Thinking in systems and not silos will help brands mitigate accusations of greenwashing because consumers are always quick to point out the damage brands are doing to various stakeholders in the system.

An example of systems thinking in action is the push towards circularity in packaging.

Hwang also writes that “brands are moving beyond basic ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ tactics to rethink full-usage cycle journeys”.

“The best scale-up brands reimagine how to achieve circularity, unencumbered by both existing factory machinery as well as traditional distribution. But what if you are a legacy brand that can’t so easily reinvent your business and distribution model from the bottom up? The trick is to close the loop on the last mile, seeing what existing partners you can best leverage.”

Another way of interpreting systems thinking is the ability to see the full picture before making and accusing misleading claims.

Our infographic shows that Aussie consumers tend to trust local brands over international ones in their green claims, especially when branded as “made in Australia”.

However, Chilewicz points out that this is a huge misconception and encourages marketers and consumers alike to take a look at the full picture, taking local capability, carbon emissions, costs and quality into consideration.

For example, Who Gives a Crap is a ‘green brand’ that sources from China, which at first glance could be a point of consumer skepticism.

Chilewicz elaborates by highlighting that “China is a key global source of high-quality raw materials, which means that our post-consumer recycled paper and bamboo are sourced locally near our manufacturers. This produces less carbon emissions than other supply chain models that ship their raw materials in from other places.”

Tackling sustainability is a marathon, not a sprint, as pointed out by Hwang in his paper. While it’s important to hold brands accountable and call them out when necessary, an environment of fear and silence will only hamper progress.

Read more in this Spotlight series

Beyond illusions, towards authenticity: Addressing Australia’s greenwashing trust gap

Stephanie Siew

WARC

Design, sustainability and accessibility: How Good Citizens’ eyewear makes ‘trash’ worthy

Nik Robinson

Good Citizens Eyewear

How sustainability is No 1 and No 2 for Who Gives A Crap

Maria Chilewicz

Who Gives A Crap

Sustainability: From “A noble crusade” to “A bit better every day”

Toby Harrison

Ogilvy Network ANZ

Creating sustainable value through system thinking

Lee Simpson

whiteGREY Australia

The Big Picture: Concerned Aussies want brands to take action

Spotlight infographic

WARC