If your current price structure doesn’t balance winning on demand, revenue and margin, then it’s not your optimal one, write Kantar’s Mary Kyriakidi and Graham Staplehurst.

This article was originally published on Kantar Inspiration and is reproduced with permission.

We have two contrasting thoughts in our minds: I believe people have now less spending power, whereas Graham believes people are willing to pay double for some brands. The truth is that we both make valid points that are backed up with evidence. Kantar Sightlines data shows that nearly half of US shoppers have 20% or less of their income left as discretionary and that private labels have gained ground with inflation. On the other hand, a deep dive into the virtues of Pricing Power – a metric from Kantar’s validated Meaningful, Different and Salient framework that represents a brand’s equity in the consumer mind – reveals that shoppers are apt to pay two times more for brands with high Pricing Power vs brands without.

Both data sets describe consumer realities, often even for the same person. Despite belt tightening, a seemingly irrational preference for some products and services remains. Even bargain hunters step out of their shopping comfort zone to pay 14% more for brands they single out as meaningfully different. But, for all of this to happen, you first need to set the right price.

If you’ve read the first chapter of our pricing trilogy, you are hopefully convinced Pricing Power is a real thing and that, as a marketer, you are able to affect consumer sensitivity to price changes. Your pricing technique is not simplistically cost-based: cost of manufacture - markup - selling price. You aspire to understand your category shoppers to work out the value you are offering customers. You are determined not to leave money on the table and you are on track to harvest the perceived value of your product or service with the optimal price. What do you do next?

Here are the three research hacks to follow to get it right and the one constant truth to activate it.

Hack #1: Gain insight from private labels

Look around you, can you see private label brands? Counter-intuitively, this might work to your advantage.

The presence of private labels shows that there is a general demand for your product category. Happy days! But equally, the cheaper competition around is an everyday business challenge, which intensifies as consumers crave for more affordability. One in four shoppers in Europe will opt for a cheaper alternative in essential categories without much beard-stroking.

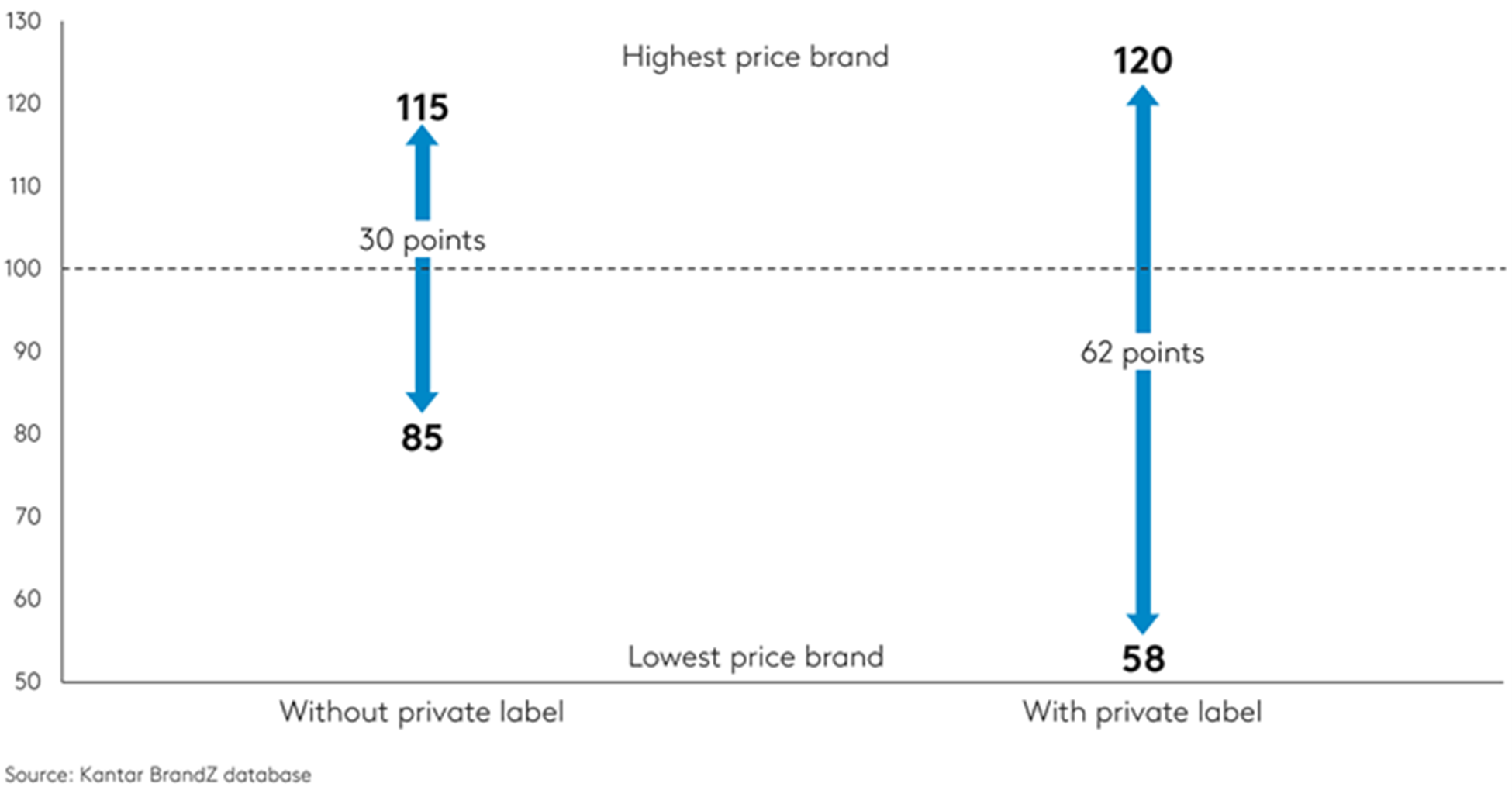

Having private labels around can be a welcome challenge. If the volume share of private labels is high, and not their value, then your category is partitioning, meaning that a proportion of buyers are opting for a commodity alternative. We analysed over 1,000 BrandZ categories and we found out that the presence of private labels doubles the perceived price range, allowing the strongest brands to extend their premium.

Range of perceived prices within category

Premium brands – blessed with brand equity – benefit in a category laden with private labels as they benchmark the top price end of the category which gets attention from retailers and customers alike. Retailers appreciate the higher margins, customers cherish better – or inferred better – quality. Our analyses show the price itself explains around 27% of the Pricing Power perception among consumers: price, unsurprisingly, signals quality.

Can your brand stretch to a top price benchmark in a partitioning category? Or else, which brand in your portfolio can retain its volume at different price points? For a beverage industry client, we studied the price sensitivity of each one of their brands, examining the impact on volume at each price point. Some SKUs were more price-sensitive than others.

Hack #2: Match your price to your brand

Successful pricing doesn’t necessarily equal trading at the super-premium end of the sector. Rather, success is defined by a perfect alignment between the price itself and consumers’ perceptions.

Around one-third of the 40,000 case studies we capture in our BrandZ database show brands whose equity does not support their perceived value. This percentage includes brands struggling to justify their price premium, in contrast to others whose equity indicates they are worth more than they are currently charging.

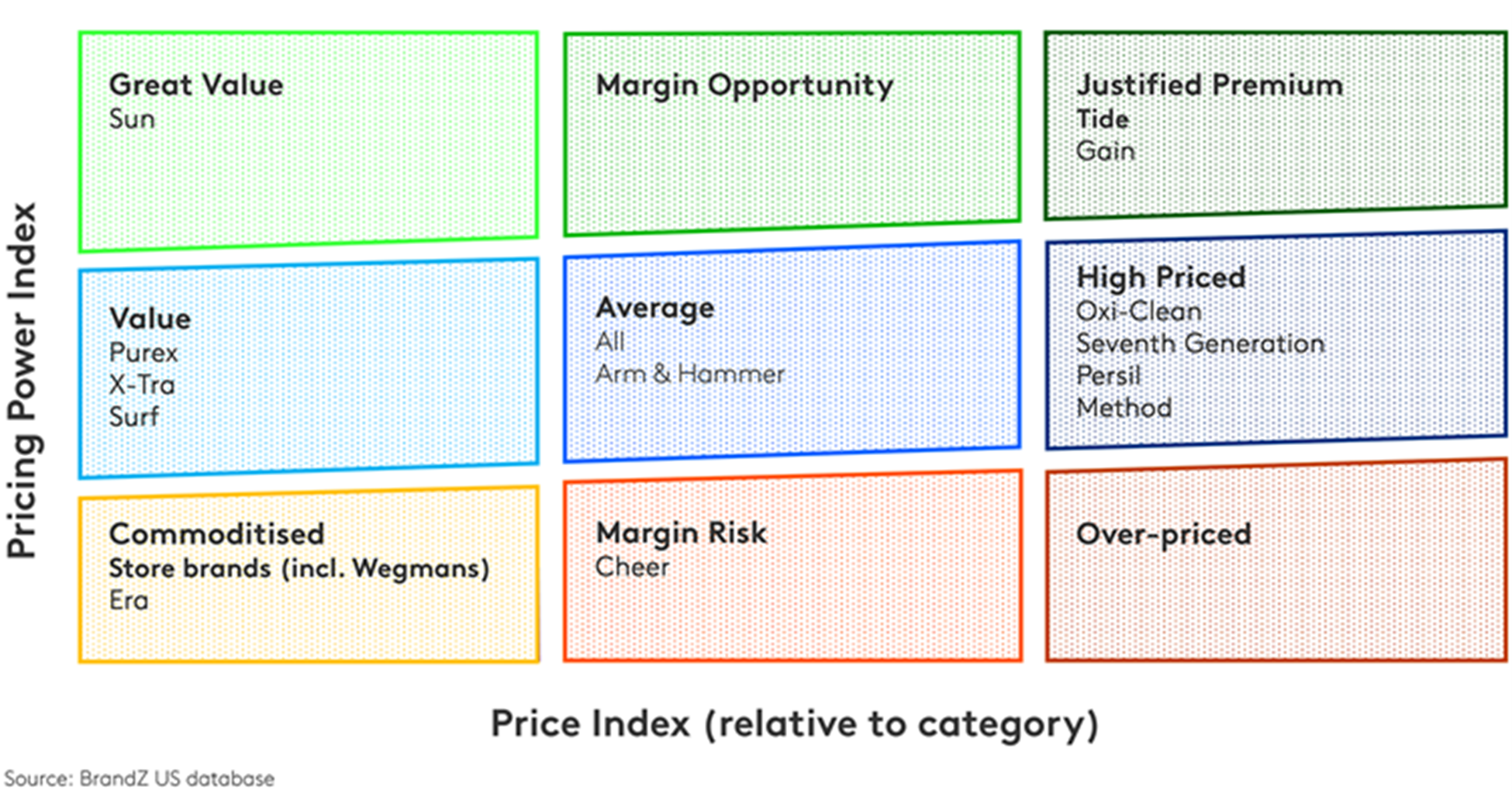

To help brands with this challenge, Kantar created a strategic pricing model that juxtaposes perceived relative price and Pricing Power. This model recently came under the spotlight again when Professor Steenkamp mused about how consumers would react in a head-on comparison between Tide vs. the Wegmans store brand. Let’s have a look:

Strategic pricing position for Tide vs. competitors

In these nine boxes, Tide and its competitors are grouped in the US detergents category based on their Pricing Power and perceived relative price. Cheaper brands (like Sun, X-Tra and store brands) are on the left, more expensive brands (like Method and Persil) are on the right. On the vertical axis, using our metric Pricing Power, we plot the equity of each brand in people’s heads; the higher up the axis, the stronger and more positive a brand’s perception among consumers. In the orange boxes at the bottom, we find store brands (including Wegmans) and Era that are over-reliant on pricing to drive sales, but also Cheer, whose pricing is out of line with how their customers view their brand. Across the middle – in the boxes where you find Surf, Arm & Hammer and Seventh Generation – are the brands that have ‘expected’ Pricing Power for the price they charge. The brands in the top green row have ‘extra’ Pricing Power. They all offer good value for their price to customers; cheaper brands like Sun are great value, bargains. More expensive brands like Tide and Gain offer enough benefits to justify a higher price than competitors.

As a rule of thumb, for every 4% increase in relative price, 1 point of Pricing Power is expected. For instance, a brand hoping to charge 40% over the category average price needs to have a Pricing Power perception of 110 to justify this. The P&G laundry detergent Tide charges 32% over the average category price: its Pricing Power Index of 112 places it firmly in the “Justified Premium” segment. In fact, 60% of consumers say it’s worth what it costs, and interestingly, 15% say it is "worth more than it costs", suggesting that US consumers will keep choosing Tide, even with a price increase.

Whatever your price point, aim for the top row: this is where the world’s top brands tend to sit, something that is equally true for Kantar BrandZ’s most valuable global brands. Because you see, Pricing Power is relevant to all brands, regardless of their price point. Taking an example from the retail world, Gyomu Super in Japan positions itself as Great Value in the eyes of consumers (top left box above), thanks to its vast range of affordable products and unique shopping experience. However, this popular wholesale grocery retailer is also perceived as both Meaningful and Different having built its Pricing Power by creating clear connections with its customers. The brand joined the Most Valuable Japanese Brands in 2023, ranking at #36, worth $1,488M.

Settle on a price position that you are confident your brand’s equity can justify. Only then can you define your strategy going forward.

Hack #3: Calculate customers’ willingness to pay

Most marketers are given a new product or inherit an existing one. They don’t participate in its creation; they take over and figure out how much it is worth to the consumer. The best approach, we believe, would be for the new offer to be based on a clear understanding of customer perceived value and their willingness to pay.

But there is no such thing as perfection in marketing. Even as a follow-up action, ‘willingness to pay’ is the single most valuable piece of information to get, yet it remains the most elusive. Let’s look at the two different scenarios of pricing a new product or reconsidering the price of an existing one. How do you go about gauging consumer’s readiness to pay?

Consumers can help you set the right price, but consumers can’t tell you what the exact price of your new product should be. However, they can help you define the different price thresholds: what is too much, what is too cheap, what is acceptable and where a change in perception would come about. And this is where Van Westendorp’s four questions come in handy. Want to get to the sweet spot of pricing success? Speak to potential buyers and get feedback within 24 hours via our agile solution.

Shopping decisions are a trade-off between value and cost, so for products already in the marketplace, Van Westendorp’s Price Sensitivity Model won’t suffice. We have to replicate real-life trade-offs in the competitive context…in the lab. Our opening is the simplest and most natural question: “If these are your options, what do you choose?" Then, our choice-based conjoint technique creates choice tasks and observes consumers as they make their product decisions. The consumers’ intersection of pain and price points (as behavioural psychologists have measured the ‘loss aversion’ response to paying for goods and services) reveal the optimum bundles and prices, accurately predict how price changes will affect volume, revenue and profit, also quantify how important different product features are for the purchase decision. The more simulations you do, the more precise they become, as the interview algorithm learns progressively and brings you as close as possible to accurate purchase behaviour.

Case study, automotive sector

In every single survey, our client‘s brand was mentioned among the most important purchase reasons. But unknown to them was how the brand’s value perception affected consumers’ willingness to pay. To help them fine-tune their price strategy and capture the value of their brand, we did two things: 1. we calculated the acceptable price ranges versus competition in the different car segments. 2. we defined price targets that allowed conquest and loyalty rates.

As the car maker better understood people’s ‘willingness to pay’ triggers, the reflex discounts eased in some car segments, whilst in others, were replaced by justified higher mark-ups.

Although this case study involved a proprietary analysis for our client, our free interactive tool BrandSnapshot powered by BrandZ delivers intelligence on 10,000 brands in more than 40 markets, and offers a quick read on a brand’s performance in a category. In the automotive category we see that some car manufacturers are charging 10-100x the price of others and are happy to make a very limited supply each year.

Emotive clarity: The trick up every CMO’s sleeve to justify their price

A good marketer drives sales and gets their sales director promoted. An excellent marketer reduces consumers’ price sensitivity, gives their brand more chances of being chosen and turns around profitability for the business.

The trick to getting your customers to be less price-sensitive is to climb up the benefits ladder, as Mark Ritson teaches us. Starting with Product, the gradual incline includes Product Features, Product Benefits, Customer Benefit and at the very top…Emotional Benefit. The higher up the benefits ladder you go, the more strength you will find.

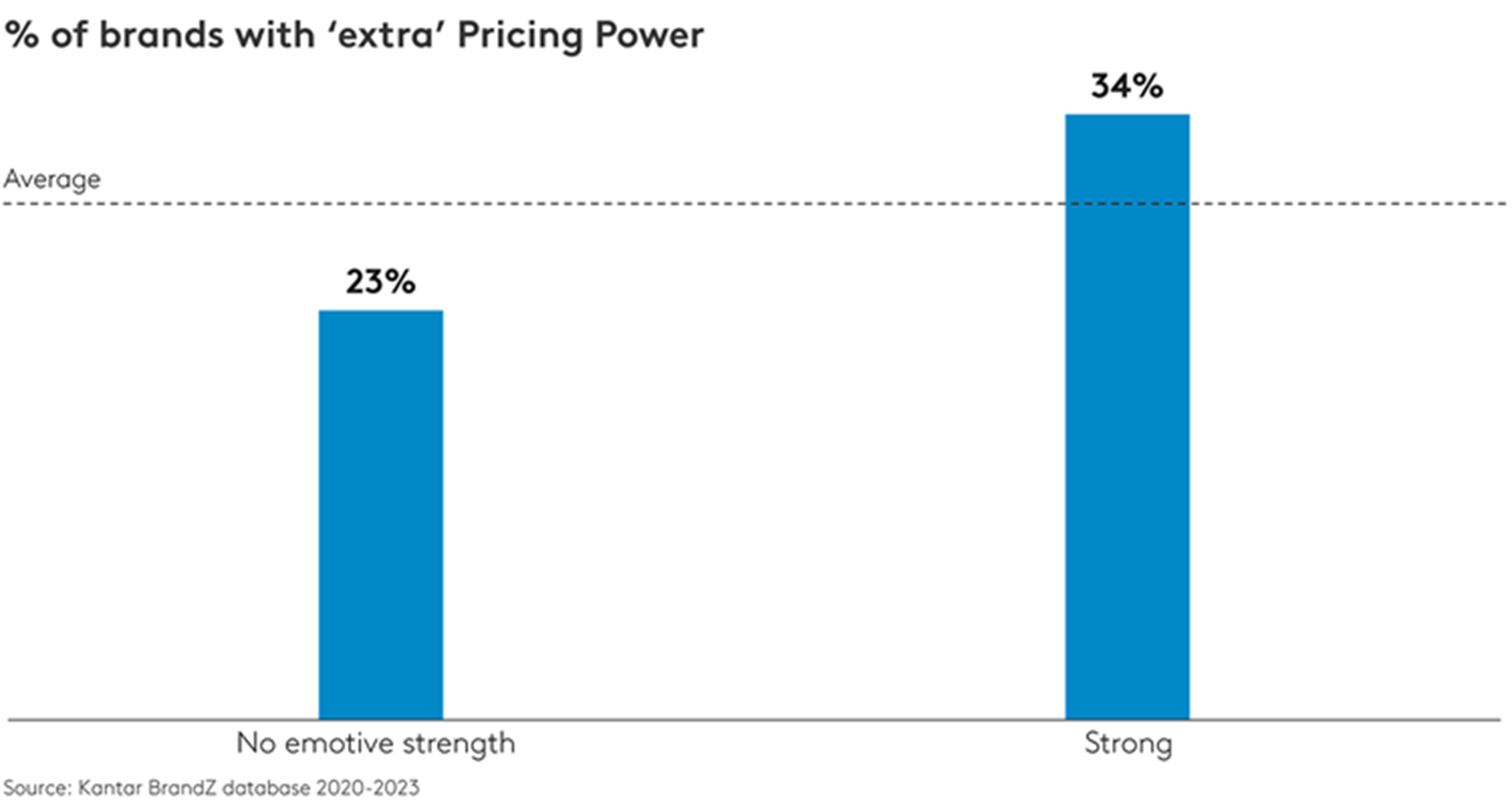

In fact, our data proves that brands with emotive clarity are 1.5x more likely to have ‘extra’ Pricing Power, which helps them justify their price. “Those organisations that manage to define and deliver a consistent emotive thread – across siloes, across geographies, and over time – are setting their brands up for long-term success. The hard-nosed business case for the soft side of branding is there, as Ryan France, our colleague and head of Brand Strategy at Kantar Australia puts it, make sure the CFO knows it.”

The secret to building your brand’s Pricing Power through marketing is emotive clarity.

Over the last 18 months, we’ve witnessed an unplanned experiment on how brand strength can help brands command a price premium despite the economic downturn. Tyrrells, the KP Snacks brand, is at the very top of the case studies: almost counter-intuitively, they leaned on their personality to suggest upmarket quality, rather than trying to convince consumers through rational product messages, achieving a 29% price increase in a price sensitive category and hitting profitability.

There is undeniably cautious spending all around us, but this doesn’t remove the opportunity to sell at a premium price point. Can your brand command a price premium? Can your brand justify a price increase? Remember, high prices as well as low prices can scare off consumers, you’ve got to find the one that’s right for your brand and your category shoppers.

Discover how to keep a permanent tab on pricing power with Kantar BrandTek equity and tracking solutions. Get in touch to find out more.