The myth that humans now have shorter attention spans than goldfish has been repeated until it’s started to resemble truth. WARC’s Sam Peña-Taylor looks at the myth that just won’t die.

Last week, I was at a conference listening to the managing director of a respectable social media agency talking about changing trends in the discipline. It was the typical infographic-heavy, information-light presentation that sought to build up the complexity of the problem of digital and, simultaneously, demonstrate its simplicity. I heard the word ‘millennials’ a lot, and because I am a millennial, I lost interest.

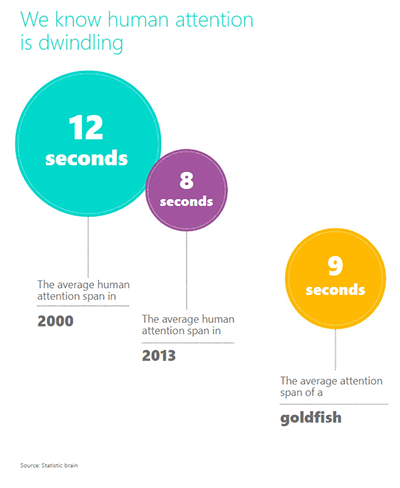

Then they brought up the goldfish thing. “Our attention span is now just eight seconds,” the person declared, wearing that grimace people deploy when they’re letting you know some real home truths. They glance around the room, watching the tension build. “That’s less than a goldfish.”

In many ways, it would be the perfect factoid. It’s easy to visualise, the silly little goldfish circling the same ring of water. We find some small mercy in it: at least its attention span is so short that by the time it repeats its path it will have forgotten about it and will find it surprising. Silly little goldfish.

At the coffee break making chit-chat, I get talking to a guy from a market research firm. We talked about the ideas that surprised us and those that didn’t. I brought up the goldfish, arguing that it was not only hackneyed and boring but just plain wrong. The response: they’re selling, he said. If it’s part of a pitch, it’s fair game. Where does that leave us?

The goldfish attention span story turns up regularly on the conference circuit, but as plenty of different outlets – including WARC, via columnist Faris Yakob – have written, it is a total and complete myth.

Not only are goldfish far more intelligent than the popular conception would have us believe – neuro-psychologists actually use them as a model for memory formulation precisely because they have memories and use them to learn – but human attention isn’t fixed. It’s flexible and task-specific.

The problem is that there’s research to back the myth up. Kind of. In 2015, the stat started doing the rounds of reputable news organisations – Time, the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, The New York Times – all linking back to a report by Microsoft Canada’s consumer insights team.

Suspiciously, those links now feed to Microsoft’s research homepage, on which I was unable to find the original document (You can, however, see a copy here). At the bottom of the page, the report sources Statistic Brain. Its website also seemingly contains no trace of this research.

A BBC article from 2017 was able to find some sourcing for the claim, but these were not only “infuriatingly vague,” but also evaporated on contact with reality. When the writer contacted the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the US National Library of Medicine and the Associated Press, neither could find any record of this research. We might conclude that such a stat, then, is unusably murky at best and purely made up at worst.

Of course, the point of the goldfish myth, as deployed by reputable social media agencies, is to urge marketers to pump money into short formats whose providers rake in colossal amounts of ad money. It suited a lot of people that the factoid caught on, taking what should have been a strategic conversation about how to grab attention through distinctiveness, and making it a media conversation.

Whether or not short-form ads are effective is beside the point. The advertising industry is already mistrusted by a majority of the public, and if the industry is telling itself lies what then? The navel-gazing that’s all too often a defining characteristic will not only accelerate the onset of its redundancy but encourage wholesale, institutionalised incuriosity.

Curiously, the goldfish myth displays some of what is actually most effective about robust creative strategy. It’s easy to remember, it’s surprising, it’s fun, it’s light on detail and easy to compare to the evidence around us. People are on their phones a lot more, they’re swiping and scrolling; shots in films are getting shorter. The suggestion that our attention spans are diminishing is everywhere.

That we’re now more distractible than a fish could just about make sense, if we don’t think about it too much. And that’s at the core of the myth’s power: it does much of the thinking for us by wrapping around an existing assumption and just slightly subverting it. As an image, it cuts through and grabs our attention when the sales pitch is beginning to drag. It’s clever.