As we race towards an ever more personalised future perhaps there is merit in reflecting on how personal brands should become.

A hyper-segmentation revolution is afoot in which bespoke, one-to-one communication at scale is the new holy grail for brands.

The right message to the right person at the right time, through the right channel, at the right point in the purchase journey.

The more tailored and personalised the better, right?

The commercial rationale for this approach is compelling; ultimate efficiency and effectiveness.

The deadly aim of the snipers’ rifle picking off consumers one by one in their own moment of vulnerability, with the inefficiency of the carpet-bombing broadcast approach soon to be a distant memory.

Using ever-richer and better-analysed data will allow brands to anticipate and answer needs ever more immediately, seamlessly and subserviently.

This idea of this intuitive, bespoke, atomized, real-time commercial singularity is as powerful and radical as it is inevitable. Yet it all seems to be missing a certain something …

Undoubtedly there are categories in which the personal, private and timely nature of such communication alone will be mutually advantageous for consumer and brand alike.

Healthcare and personal finance are surely two such prime contenders.

The one-to-one model’s shortcoming is evident in its name; it assumes that there is no-one else in the story. That the relationship between brand and consumer is purely transactional and discreet. In reality however, our emotional relationship with brands and the role they play in society seems rather more complex.

The human desire for belonging is a universal one. Conversely the fear of missing out (FOMO) is a very powerful motivator.

We all have an innate desire to be a part of a common narrative and the language that shared cultural experience provides. Brands are an important part of that, they’re a shared language.

For that logo on your shirt to convey the meaning that you want it to, the person sitting opposite you on the bus needs to have a shared understanding of the brand it represents.

The brand needs to exist in culture at large.

Communications themselves also work in a similar way. The ability to share in the emotional reward of being ‘in on the joke’ is predicated on the fact that the joke was not written and told only for you.

There is, therefore, intrinsic importance in the shared experience of ‘un-personalised’ content. Reassurance in experiencing what others experience; the sense of belonging that it fosters and, critically, the common meaning it establishes.

So while personalisation presents huge opportunities for brands, in most categories the question is perhaps not as simple as ‘How personalised can we be?’ but instead ‘How personalised should we be?’

In the era of personalised products that will follow more personalised communications, this question is only likely to become ever more pertinent and is likely to present an even more existential threat to very idea of a brand itself … but let’s leave that for now.

All of which brings me to the Heineken Champions League sponsorship case study, a winner at this year’s IPA Effectiveness Awards (disclosure – I also happen to be its co-author).

Few subjects are more about shared experience than beer or football. So what makes this paper interesting (even if I say so myself) is the careful balance that Heineken’s communications struck between the highly personal and the shared experience.

A global macro-narrative very actively created FOMO across 81 markets – with Jose Mourinho dramatising a sense of event and the ‘unmissibility’ of matches. Market level activation was tailored to have specific relevance at the time of day that the game was on – which naturally varies greatly around the globe. Meanwhile personalized messaging was customized right down to the individual.

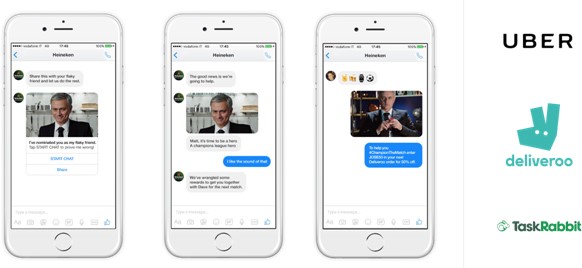

We set about debunking excuses that guys were giving for missing a match – addressing factors such as weather and local events based on location, allowing friends to generate their own content, a chatbot to help them do so and even occasionally setting Mourinho himself on unsuspecting excuse makers.

The Mourinho chatbot from the Heineken UEFA Champions League campaign could be used to deliver custom ‘excuse busters’ among friends.

This sponsorship activity served to reinforce Heineken’s credentials as a cultural force – specifically as the beer for match night with your mates. At the same time it prompted a deeper and more meaningful personal affinity with the brand.

It serves to illustrate that personalisation not unlike Heineken itself, is at its best when served in moderation.

Please enjoy responsibly.

To read the full case study visit: 'A game changer: How Heineken reinvented its champions league communications'