New brands can’t come into existence without consumers, but consumers won’t always pick the winner, says Ben Osborne.

It’s impossible to develop a new brand idea in a meaningful way if you are working in an echo chamber. It’s critical to give a voice to your audiences, and to understand what resonates most with them. However, when testing ideas with consumers you sadly can’t trust them to pick a winner for you – it’s more complicated than that.

Consumers react more positively to the familiar than the new. Think back to a time when a much-loved brand made changes to their visual identity and the resulting controversy that followed. For example, in 2015 the Google logo was updated to adopt a new font and system designed to optimise greater compatibility across devices and unify architecture under Alphabet. What followed was a barrage of technical criticism from designers, a general sense of unease with the new, and consumers nostalgia for the old.

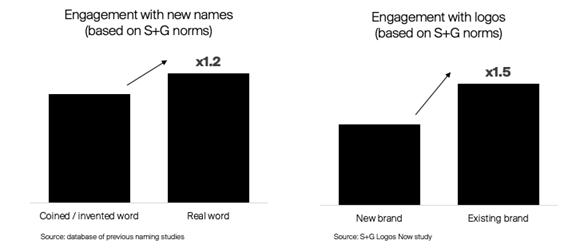

When asking consumers directly about their preferences between different brand options, in an artificial context like a focus group or questionnaire, they are even more likely to default to reject the unfamiliar. Siegel+Gale research has shown that consumers are 50% more likely to claim to have a positive reaction to a visual identity previously known to them than they are to a new one they’ve never seen before. Furthermore, they are 20% more likely to engage with a brand or product name derived from a real-world word than they are to a new, invented word.

But in the real world this bias rarely matters. New brands, with innovative, disruptive and creative ideas, designs and names are launched and thrive. Within a matter of days changes to a known brand become normalised and no longer feel unfamiliar or unknown. Brands that stand still or don’t differentiate themselves fail.

So how do you test your ideas with consumers and robustly choose between different branding routes in a meaningful way? There are three Golden Rules to ensure consumers are included in the process whilst at the same time not out-sourcing decision-making entirely to a naturally biased and unqualified audience.

1. Consumer research is closer to trainspotting than a beauty parade

Whether deploying qualitative or quantitative methodologies, research should be framed as a way of understanding the potential of each route and where it takes the brand rather than giving end-users a beauty contest to judge.

Think of your different routes as trains on adjacent platforms of the Underground – we’re not asking consumers to evaluate which train looks the best, but instead to tell us which train has the most appealing end destination and why.

Taking this further – the agency team should evaluate the strength of each branding route and make recommendations based on which best fulfils the project objectives, and not be tempted to report head-to-head scores.

2. It’s impossible to understand anything out of context – but we can also manipulate this

We rarely discover new brands or ideas in insolation of multiple layers of meaning and context – both at the category and brand level. It is essential that we provide these cues and this context, but also isolate its impact.

For example, if testing a new name, we first need to ensure that we understand reactions to it as a ‘word’ – does the word have positive or negative associations, does it sound like something else, is it hard to pronounce?

Then we need to understand it as a ‘name’ in the category – is it appropriate or credible for a company or product in this specific industry. And finally, we need to evaluate the name as a ‘container’ for the ambition and strategy behind the brand – can the name support the brand and does understanding the brand deepen the appeal of the name itself and give it more meaning.

3. Reveal your ideas bit-by-bit

Rather than showing different options side-by-side, inviting the biases above, it is important to explore each idea independently by really digging into the individual elements of the brand. Each idea should be built iteratively in order to isolate individual moving pieces with the potential to highlight priorities for refinement.

For example, we would recommend isolating the name from an idea or visual identity – robustly understanding its potential in its own right. Then add meaning or a story to this name, to explore the potential of the name + story / idea. Then we would visualise the brand and explore reactions to name + story / idea + design. This visualisation could be a logo, but also a handful of different notionals in real-life situations to bring the brand to life.

Moving forward

In short, it’s critical to give a voice to the consumer, but we can’t take for granted that they can speak the language of brand. Research can be used to bridge this gap, giving customer-centric design credibility.