Elon Musk’s apparently chaotic takeover of Twitter is not a scaled test and learn but instead suggests a strategic void that threatens to undo the entire Musk brand.

Over the course of 2020 and 2021, the Covid years, from the time it was a scary but couldn’t-happen-here international news story through to it being the only story, the British government developed a radical new strategy for navigating a public health crisis.

It wouldn’t tell people its plan at once; it would instead leak out potential plans, ideas, new kinds of restrictions, the days those restrictions would end, or which businesses could and could not open. Then it would gauge the reaction, refine, and then formally announce.

It was like a kind of ultra-high-stakes, chaotic, and unscientific test and learn process.

Trouble was that everyone could tell that there wasn’t really any sort of plan. We had mostly intuited that clear communications tend to stem from clear strategy while mixed, uncertain comms imply chaos at the top.

Effectively, through anonymous briefings to certain journalists – who then often posted these briefed details to Twitter immediately – it would launch scraps of information into an informational free market (but one far from perfectly efficient). The ideas that were well-received were always the plan, those considered idiotic would be dismissed as idle media speculation.

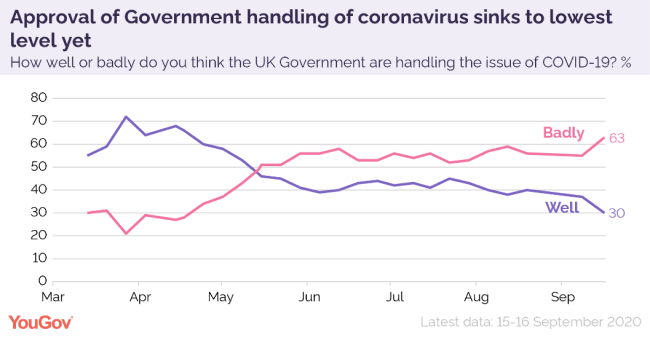

Depending on the metric you looked at, it worked. If your favoured metric is approval ratings, election style, then the strategy worked pretty well, at least at first. Based, however, on confirmed cases and then excess deaths, it was a very different story, one that has led to a national inquiry.

While the inquiry may not examine the communications strategy directly, the chaos of the approach, which led to individuals feeling the need to act according to their own assessment of the situation while they waited for government advice, and intra-familial disagreements, is unlikely to go down as public health communications best practice.

Or any best practice. It’s not a way to run a government and it’s not a way to run a company. But fast forward two years and there are strange parallels with the takeover of Twitter by one Elon Musk, which from the outside appears pretty chaotic.

To some, Musk is a genius of the highest order whose ambition is almost single-handedly pushing the boundaries of humanity through private enterprise to space, to Mars, and beyond.

To others, he’s an increasingly problematic, occasionally vindictive show-off whose companies’ engineering achievements (and the massive personal net worth it has brought him) have led him to believe his own hype. He also has 113 million followers on Twitter and an army of acolytes to cheer him on.

While I’m not suggesting that he’s taken a leaf out of the pandemic-era UK government – or that the stakes are even close to similar – when deciding how to run the hugely influential, if commercially underperforming Twitter, there’s a similar lesson to be taken.

That is: if you’re really good at one thing (whether that’s running a rocket company or winning elections) it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re great at everything else (running an ethically complex media platform or leading a country through a public health campaign), and accepting this reality and perhaps adapting your style may be helpful in the long run.

On the balance of current news, a switch doesn’t look likely given the progression from offering $54.20 a share for the lolz, to the limp attempt to get out of a contract he forced, to publicly trashing the company, to eventually and theatrically relenting, to the sacking of executives and as much as half of the rank and file.

Now firmly behind the wheel, the method appears to be leadership by tweeted decree, where the self-appointed “Chief Twit” throws out feature and policy proposals and gauges the reaction. But then doing things anyway.

There’s the $8 per month verification scheme, which was initially $20 but then the billionaire appeared to mistake legitimate concerns about identity as a pricing issue. New features like paywalled video and previously defunct features like Vine are being mooted and rushed through.

But it is getting serious. Advertisers, who currently pay the bills, are holding fire on spending amid the chaos on top of a wider secular decline in digital advertising. Other brands appear to have “quiet quit” the platform.

The goodwill of others matters too, not least the creditors to which the company (onto which some of the debt of the purchase has been loaded) owes around a billion dollars annually just servicing the debt, let alone paying it off. Some of the banks involved are considering withholding debt until they see some serious plans; in their absence, the banks are preparing to take a hit in order to offload it.

Knowing how to read and react to a backlash matters to businesses. The billionaire has made a very successful career out of making very big promises and often fulfilling them, but the promise of an "everything app" is a very big one indeed, and which requires lots of users beyond the hardcore fans.

While hoping that Twitter doesn’t collapse in the process, this is a strange new kind of test for Musk and his genius aura – his brand, if you will – which has arguably done as much to attract and retain investors as it has to build fame way beyond the high net worth buyers of Tesla cars or SpaceX services.

Tesla famously spends nothing on advertising, but its brand relies heavily on Musk’s reputation for competence. Should the sheen come off the founder, it might discover the limits of that model.

But it will be interesting. I’m just thankful he’s not my boss.