At Brainy Bar 10, experts discussed the neuroscience behind the idea of the gendered brain, and the importance of external messaging and stimuli to the establishment of gender – Sam Peña-Taylor reports.

“If the outside world is telling you something about yourself, it’s going to have a profound effect on your behaviour,” explains Gina Rippon, professor emeritus of cognitive neuroimaging at the Aston Brain Centre, part of Aston University.

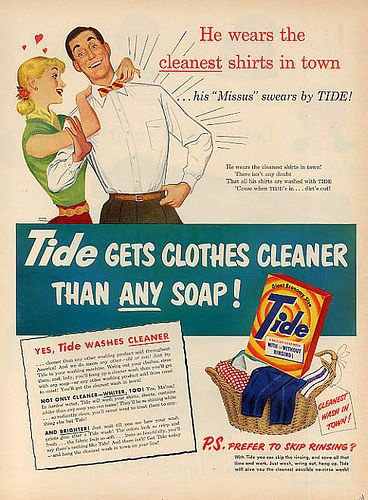

From an advertising perspective, it is reassuring that the work of promotion and persuasion can indeed work. But it is far less reassuring when considering the issue of gender: advertising has quite the charge sheet to answer in this regard.

A prime example...

But Professor Rippon’s central thesis, explored in her 2019 book The Gendered Brain, takes on the pervasive assumption that there are certain aspects of the brain that define our gender. Instead, the brain is constantly adapting to external stimuli, capable of life-long learning; but it is also seeking out groups in which we belong, in which we feel good and avoiding those in which we feel bad.

So what if since the very beginning – even before the beginning – of a person’s life, the outside world starts pointing you towards the colour blue if you’re a boy and pink if you’re a girl, as in the manner of the modern day ‘gender reveal’ parties? And anyway, “they're not gender reveal parties, their sex reveal parties,” Rippon points out.

We continue to confuse sex with gender. This places limitations on everyone. If the conditioning process begins so early and continues to self-fulfill throughout a lifetime – and there are many, many ways in which the idea of what a girl or boy is and how they ought to behave are reinforced every day – how can it change?

Rippon was speaking at the 10th Brainy Bar event, held in central London this week by Walnut Unlimited, the multi-faceted research agency with a specialism in using neuro and behavioural sciences to understand advertising, and supported by WARC.

Introducing Rippon, Walnut founder and board director Dr. Cristina de Balanzo points out that marketing cannot continue without a knowledge of her work if it is to cease being an industry “soaked in accidental sexism”.

At the brand level, this is changing – albeit slowly. Efforts from former gender-reinforcing culprits, such as Mattel’s Barbie, have begun to engage with these ideas in their brand thinking.

It’s a recent development, beginning with Dream Gap in 2018, which sought to demonstrate to young girls that their potential was not limited by their gender, for instance, and now continuing into a more sophisticated message that doll-play is not only for girls, but for any and all kids, explains Mattel’s head of insights and analytics, Michael Swaisland.

But there are many perceptions that the brand must win over, not just the kids you have to get excited about a toy; there are the parents, of course, and then the friends and relatives who buy gifts for the kids. “There’s a lot of layers here,” says Swaisland, who was speaking on a panel at the event.

Advertising thinking is starting to adapt, not least because it makes no sense to limit an addressable market. But engrained ideas of gender persist: where did they come from?

The inside-out brain

Many people believe that our brains are inherently gendered, and that there are qualities that the male brain possesses that the female brain simply does not, and vice versa. This is known as the biological essentialist argument, thought up by the gentlemen naturalists of the late 18th to 19th centuries.

They saw there were two different types of bodies, so whatever caused those differences meant that it also caused differences between brains. “If you had a female anatomy, you had a lady brain; if you had a male anatomy, you had a man brain,” said the essentialists. “And these brains were fixed.”

Of course, what was really going on was that these scientists were working backwards from what they observed in society. They inferred from men’s superior positions in society an intellectual superiority. Women’s seeming intellectual inferiority was perhaps softened by a moral superiority: a “sop to the fact that they’ve been short-changed on the brains,” Rippon notes.

And yet, this isn’t some abandoned position. We might have dropped the superior/inferior dichotomy from modern thinking, but the idea persists that men are better at some skills (spatial cognition and maths, for instance) while women excel in others (empathy, nurture, by contrast).

The outside-in brain

Rippon’s challenge, then, isn’t that there’s no such thing as gender, but that any difference doesn’t come from within. This is supported by extensive reviews of the available brain-imaging research over the last 30 years since the technology became available, which find no consistent differences between the male and female brain. But again, the world as we see it would suggest otherwise.

So what’s going on? Rippon begins by breaking down three fundamental qualities of the human brain:

- Predictive: “The brain is not just a classic information processor, it actually works out the rules of engagement”, based on the resulting stimuli from a particular choice, which it then uses to work out what to do in the future.

- Plastic: Science used to think that plasticity was an aspect of the growing brain that stopped in adulthood. But in fact the brain constantly changes based on new experiences. However, the opposite is also true: “If you don’t have those experiences, your brain will not be changed. And that’s quite important when we’re talking about stereotypes.”

- Permeable: The brain is extremely receptive to the positive or negative suggestions of others, which it uses to prime. For instance, a group is given a task to carry out but is told that people like you don’t tend to do very well, and another is told that people like them do tend to do it very well. The positively primed group “make half the mistakes, whereas people who got the negative message may not even try and solve the problem”.

The social brain

These three aspects of the brain are part of our interaction with the outside world of others. For a social brain, then, the sense of belonging is paramount. Social groups give us all sorts of signals where we’re told whether our experiences are positively coded and are good to remain and flourish, or negatively coded and we’re shown it’s not for us and we seek to leave. Ultimately, we want to feel like we belong – this is critical.

Rippon explains that the brain has what is known in the business as a “Go/No-go system”, like a set of traffic lights. This system is extremely powerful: positive experiences teach us that the next time we encounter a similar decision we know what we should go for. If it is negatively coded, and chips away at our self esteem, the “network of activation is very similar to the same pattern of active network of activation when somebody is suffering real pain. So this isn't just a metaphorical effect,” says Rippon. Too much of this and you start to really change the brain.

The early brain

While the brain continues its pattern of trying to avoid pain throughout the human lifespan, it’s particularly problematic for kids – “tiny social sponges” – who grasp very early on that in order to survive they need to work out where they belong.

For this reason, early stereotyping can have a massive effect. Research from the toy firm LEGO, in association with the Geena Davis Institute found that children, like their parents, are far more likely to imagine creative professionals as men than women. These restrictions are deeply limiting, explains Rippon.

“What goes on outside the brain is really important. A gendered world can produce a gendered brain.”

So what’s the recipe for inclusion? Rippon offers something of a formula:

“We need to demonstrate that people can see themselves in what’s out there. [We need to demonstrate] people can see themselves in a good light, because their brains will be steering them towards that. And we need to make them say ‘yeah, I belong to that group.’”