A delayed train in Switzerland, and the response of staff, show how an understanding of a customer’s emotions is as important as delivering on the promised function.

Back in those hedonistic days of early 2020 when we were allowed outside, I found myself on a train flying through the Swiss countryside. I was with a group of 30 septuagenarians who were on two-week rail holiday, doing some research into what made their experience great and what could be better.

One of my colleagues is from Geneva, and when she found out I was going, repeated what we’re all told about the Swiss railway. Wonderfully efficient, best in the world, will never let you down. In short, it puts our railways to shame (although in fairness a horse and cart with free working wifi would be a decent challenger to the UK offering).

So I didn’t expect the train to break down halfway through our journey. But perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised that I also got to see how to deal with a problem brilliantly, so brilliantly that it makes customers want to, well, write an article about it.

The journey started well. The train left on time and had decent leg room, big windows, and a restaurant car with knives, forks, and actual food. And when I felt that familiar jolt of the emergency brake appeared, my first thought was ‘that’s nice, they’re really making the effort to make us Brits feel at home’.

Of course, by the time the train had stopped I was already mentally preparing my sarcastic messages to my Swiss friend and my angry messages to the Swiss rail twitter team. Train broken down, we’re going to miss the connection, no-one has any idea what’s going on… typical Swiss inefficiency.

Photo by Henry Becker on Unsplash

But before I had the chance to hit send, something unexpected happened. Or at least, unexpected to those of us who travel on UK trains frequently (with the exception of the brilliant Chiltern Railways).

The train manager, fresh from giving an update over the intercom, appeared in our carriage and made a beeline for our tour manager. He sat with us and, without hesitation, apologised. Not a ‘sorry for the inconvenience’ apology, but a proper, hand on heart apology for letting us down, and for the problems this was going to cause for a large group of tourists hoping to enjoy a stress-free holiday.

I thought that was pretty impressive. I didn’t realise he was just getting started.

He laid out exactly what would happen next. Our revised time into Zurich. The next train that we could get to replace our missed connection. The platform it would leave from and the quickest way to get to it. Then he disappeared to the next carriage to speak to more passengers. Not all heroes wear capes.

As the group were chatting amongst themselves about how good the train manager was, the Tour Manager’s phone rang. He looked serious, then surprised, then delighted.

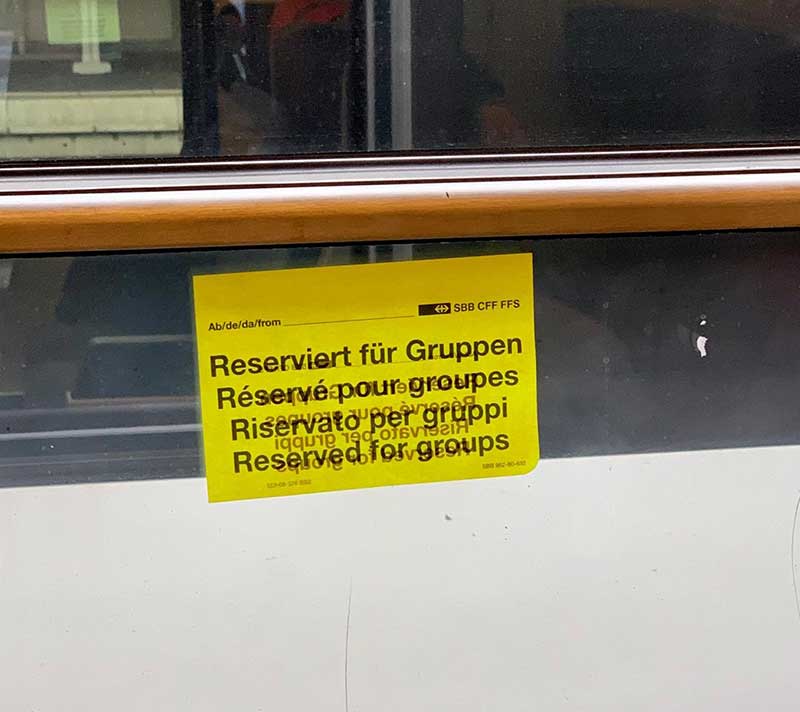

‘I’ve got an update everybody’. We all listened intently. ‘That was one of the Swiss Rail Operations Managers. He’s confirmed the train and the platform we need to get at Zurich, and has reserved us a whole carriage on that train so we don’t have to worry about finding seats together’.

Photo: John Sills

As I sat trying to work out if I could ever imagine a world where that would happen on First Great Western, the train started moving again, and before long we were in Zurich, clear and confident on which train and which platform we were heading to.

Not that we needed to be. As the train doors opened, a station manager was there to greet us. He gathered our group together and escorted us to the new train, leading us to the exact carriage that was reserved for our group.

Once we were all on, the new train manager came along to check we were all settled. And given the problems we’d had, gave us all free drinks vouchers for use on the trains at any point during the rest of the holiday.

When the train broke down, it was 14:50pm. When we got on the new train, is was 15:45pm. And if I’m honest, I kind of wanted it to go on a bit longer to see what else would happen. Free money? A train each? The Freedom of the City of Zurich? It felt like being in a real-life version of the Monty Python ‘Dirty Fork’ sketch.

This story may seem like a one-off, an exception to the rule, or to what’s possible for most businesses. But even if the scale is hard to replicate, the basics of what Swiss Rail did are simple.

First, they owned the issue. No half-cut apology about things out of their control. You’re on our train, we’ve promised to get you somewhere, and we’re not going to deliver on it. We’re sorry. Actually, genuinely sorry. This is our fault.

Next, they explained the problem. This is what’s happened, and this is why it’s happened. A real adult-to-adult conversation which shows that they understand the issue, without hiding behind policies, processes, or an evasive ‘you’re not allowed to know that’.

Then, they solved the problem. Not the functional problem of fixing the train but the human problem of us getting from A to B in a relaxed way. The train manager, knowing he had a big group on board, immediately knew the implications for us. There was no suggestion we should fend for ourselves, instead a real sense that he wanted to make sure they delivered the service they’d promised, and took any stress, worry, and hassle away.

Own the problem, explain the problem, solve the problem.

The reason for doing this isn’t just to get a good score on a bonus-influencing feedback survey. Even if the service is delivered without a hitch, customers still waste a huge amount of mental effort worrying if companies are really going to keep their promises, based on past experiences of things going wrong and not being dealt with. The functional experience may be fine, but the emotional one isn’t.

Proving that you’ll own the problem, explain the problem, and solve the problem even in the most trying of circumstances gives your customers certainty for the future that if something does go wrong, you’ll be there to sort it.

And it might save your poor embattled social media manager from a few unpleasant messages, too.