With revelations that the social networking giant ran a smear campaign against its fast-growing competitor, the fallout points to a critical lesson when marketing to youth: maybe young people want to be corrupted.

“Not another ‘what marketing can learn from x’ piece!” you cry. And across the city, the head of WARC’s editorial department hurls his phone out of the window in fury. But hear me out, because it’s a short and simple one. I might even try and do it as a dance, see if it goes viral.

The likelihood is you’ve seen the Washington Post’s exclusive about Meta (FKA Facebook) paying a consulting firm to “orchestrate a nationwide campaign seeking to turn the public against TikTok.” A bit shady, no doubt, but part of the rough and tumble of Silicon Valley, right?

The participants’ own words tell you much of what you need to know. A director at the firm, the ominously titled Targeted Victory, told employees in an email to “get the message out that while Meta is the current punching bag, TikTok is the real threat especially as a foreign owned app that is #1 in sharing data that young teens are using”.

This was a recent campaign, more recent than I had initially thought. But it followed in a long list of worries about TikTok that had culminated in the multiple executive orders. These were signed in August 2020 and threatened to ban TikTok transactions if parent company ByteDance, which is headquartered in Beijing, did not sell or spin off its US operation.

It was quite a saga, straddling the contentious 2020 presidential election, which even involved the deadline to sell passing and the then administration – whose then president made Chinese threats to national security a critical aspect of his platform – just kind of forgetting to enforce the orders. Yet, it was also just one of many general controversies around TikTok inside and outside the US: the British, Irish, and Italian data regulators have all investigated or continue to investigate data protection issues ranging from the protection of children’s personal information, to transfers of data to China.

Speaking to the Post, a Meta spokesperson defended the campaign: “We believe all platforms, including TikTok, should face a level of scrutiny consistent with their growing success.”

And yet, those concerns aside, the app has just continued to grow, trebling its user base between 2020 and 2021, and not just among children. Some of the fastest growth was, puzzlingly, among those older than 35. Still, this remains a youth phenomenon, for good or for bad.

But it grows more complex, as other sources continue to register very mixed opinions of TikTok among US audiences, with older audiences also generally more sceptical. Around 34% of US adults view TikTok unfavourably compared to the 39% that view Facebook unfavourably.

Much of the coverage the campaign elicited surrounded trends that were proliferating on TikTok such as the “Devious Licks” challenge, which revolved largely around stealing bathroom items, usually from schools or other educational institutions (??). But what was interesting was its capacity to set off a moral panic.

As the Gimlet journalist Anna Foley, whose reporting on the challenge is noted in the Post’s report, commented, Meta’s campaign is working – sort of. “[W]hen i was reporting about devious licks, a lot of the adults were clearly terrified of tiktok, but couldn't articulate any reason beyond the trite ‘it's corrupting our youth’ [sic]”.

And there it is. And we’ve been here before. Heavy metal, punk, hip-hop, skateboarding, video games – all accused of corrupting “our” youth. But what if the youth want to be corrupted? Certain categories already do a lot of business selling against people’s paranoia, but the ultimate elixir of marketing to the youth would surely be to sell against parents’ paranoia.

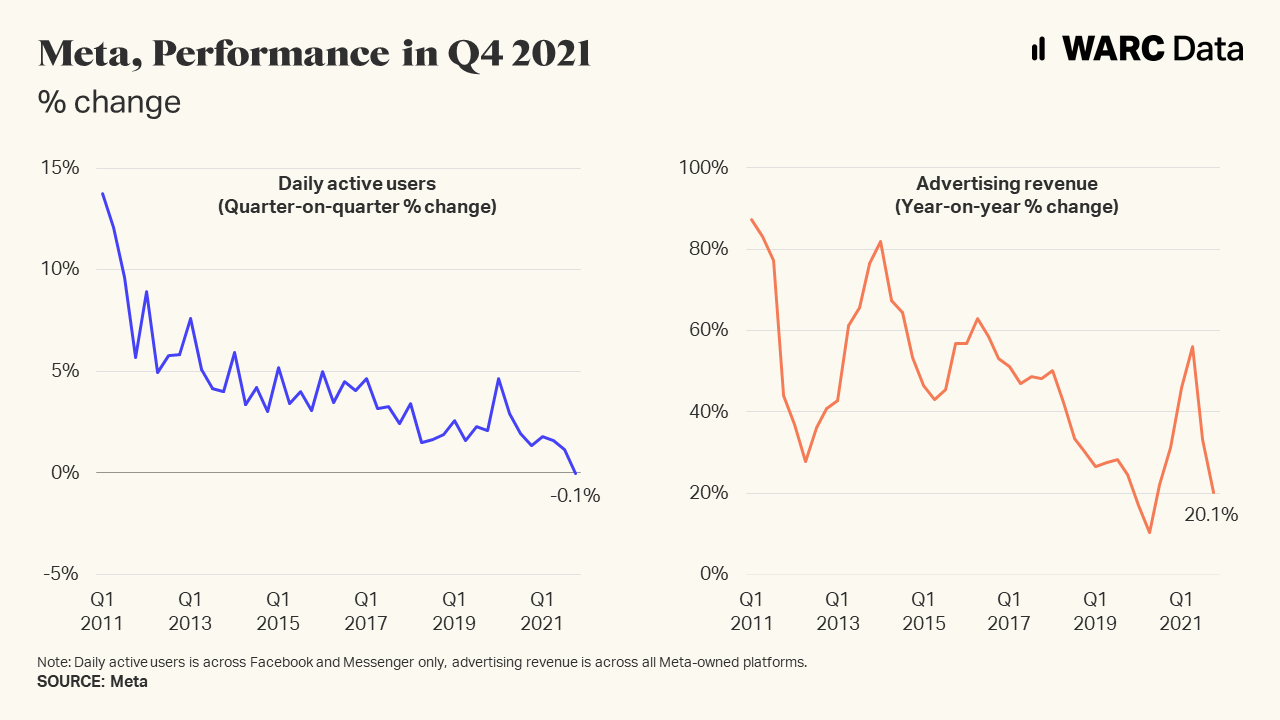

Which is why this whole affair has backfired so spectacularly. In an attempt to stem the exodus of users from Facebook (the app), Meta helped stoke a moral panic among the traditional media, many members of which picked it up. It’s now ended up with egg on its face, and added to a string of snafus that range from major systemic problems at the company to examples of a will to have the competition banned or severely curtailed rather than actually compete.

Young people want a space in which to define themselves: and that’s difficult to do on Facebook, considering all those pending friend requests from your Mum, Dad, and every aunt and uncle you didn’t go on social media to chat with. Perhaps the trick might have been to send all the adults onto TikTok so the kids would come back to Facebook. Because at the end of the day, TikTok’s success is about much more than its product: it’s as much about catching a wave as carving out a space. For today’s youth, TikTok is both.

So be honest: if you were 16, where would you rather be?