McDonald’s recent productless and restaurantless spot is an ad that plays with a deep cultural understanding and recognition – WARC explores how the brand built itself into a behemoth capable of playing around with its most recognisable signals.

It’s the ad that launched a thousand (probably more) Twitter threads and LinkedIn thought pieces. Suddenly, it seems everybody – and I mean everybody – knows who Edgar Wright is, and that it really means something to have him directing.

McDonald’s new spot in the UK briefly seemed to buck the very laws of marketing gravity by omitting both McDonald’s food and restaurants and its ‘Bah dah bah bah bah!’ jingle/sonic branding, in favour of the distinctive creative vision of the director of Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz. (Had to look that up)

Fancy a McDonald’s? is a fun ad, rhythmic and quirky. No, it doesn’t show burgers, wraps, or coffees, but it does make subtle but significant use of Maccie’s distinctive asset: its ‘M’, the golden arches.

The point of this piece isn’t to consider whether this ad is going to work, given that we won’t know that for some time – even if some of the early research from effectiveness firm System1 suggests that it scores high on brand recognition and short-term sales – but rather its strategic background.

It’s not the first time it has played with its assets. In a recent campaign in Sweden, by Nord DDB Stockholm, the brand celebrated its golden arches through the resurrection of the now-resurrected curtains haircut, framed here as the “McDo”.

To be recognised is, obviously, a key aspect of effectiveness – as WARC explores in the Anatomy of Effectiveness 2022 edition – but for strongly recognisable brands, there are great opportunities to play with that core work and make of it something exciting and surprising.

Assets and recognition are one thing, and the fact that it’s simply an enjoyable short film are another. It wasn’t, however, total creative alchemy; according to Leo Burnett’s Head of Planning, Thomas Sussman, writing on Twitter, the eyebrows were the result of a piece of smart and surprising ethnographic research. Quite what sparked this will be fascinating to understand.

But, as plenty of others have pointed out, this kind of work can only be made once the hard yards (and significant costs) of building up that meaning among the public have been made. But just how hard was that work?

In a Gold-awarded 2022 IPA Effectiveness paper submitted by long-time creative agency Leo Burnett London, the brand tells the story of how it shifted its strategy away from growing through new store openings and toward getting people to spend more when they do visit, following five years of terrible PR and stagnating sales.

It’s the story of a brand that moved away from an aggressive fire-fighting tone to one of confident humility, and which set about linking its brand to an existing culture around McDonald’s, first to reverse a decline in trust and then to defend its share against new entrants and consumption occasions.

But what’s crucial about the paper is the sheer length of time over which this work was done: 2006 to the present. This means that there’s a whole generation of kids and young adults that simply don’t associate McDonald’s with early noughties PR houndings from Supersize Me to Jamie’s School Dinners.

Instead, it positioned itself as a brand for everyone: young and old, rich and poor, blue or white collar, day or night, at home or in-store, and fundamentally as a brand that won’t break the bank. But this took 15 years of consistent work.

Then there’s the product focus of all its previous. That decade and a half saw the ads’ characters eventually sinking their teeth into big macs of stunning structural integrity, or taking long, sensual sips of a Maccie’s coffee as if they weren’t tongue-torchingly hot (which is not a criticism - if I get one, I want it to stay hot!).

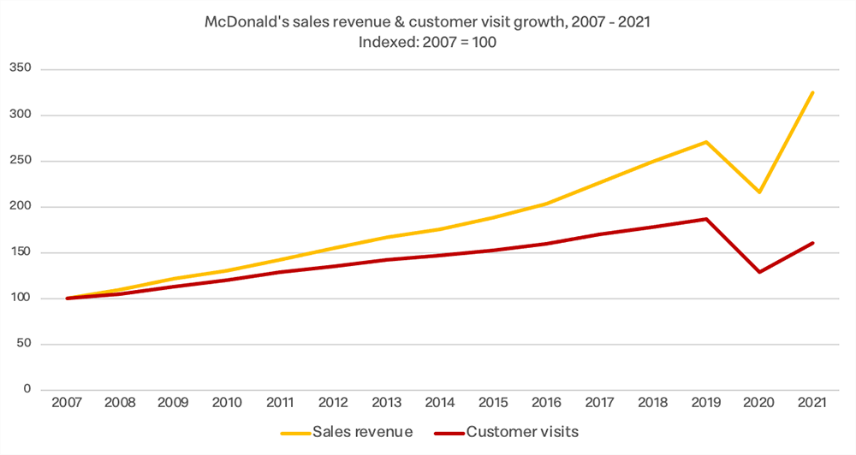

This has, evidently, worked very well until now. Borrowing from the IPA paper again, take a look at the sales revenues compared to store visits:

The outcome has been to grow incremental sales over time, and while new products have been important, the engine of growth has remained the core range of ‘Icon’ products.

Following 15 years of brand building in tough circumstances, McDonald’s – like most mass market British brands – faces a new set of challenges as the economy enters a new and more complicated phase defined by rising prices or, in short, leaner times. For market leaders in the space, the objective is likely to shift to defending market share and spending. It’s fun, it makes you feel good toward the brand, which is essential to reduce price sensitivity.

The new spot continues the work of playing on the culture around McDonald’s too, one that has developed apart from its elder American sibling brand into something quite distinctly British, and in its British sense a McDonald’s is a cheeky, vaguely naughty treat. The spot does this beautifully, communicating not only the “shall we?” but the “oh, go on then” response. Whatever it achieves, it has managed to get a lot of people talking.