The 2017 edition of the WARC Prize for Asian Strategy saw the overwhelming presence of emotion-led campaigns making the shortlist. WARC's Asia Editor Gabey Goh takes a look at the potential reasons.

The WARC Prize for Asia Strategy was first launched in 2011 to reward brilliant strategic thinking in marketing in Asia and marks its tenth anniversary in 2020. When the WARC Research team looked at the archive of case study papers submitted since its inception – a curious spike emerged in the crunching of data.

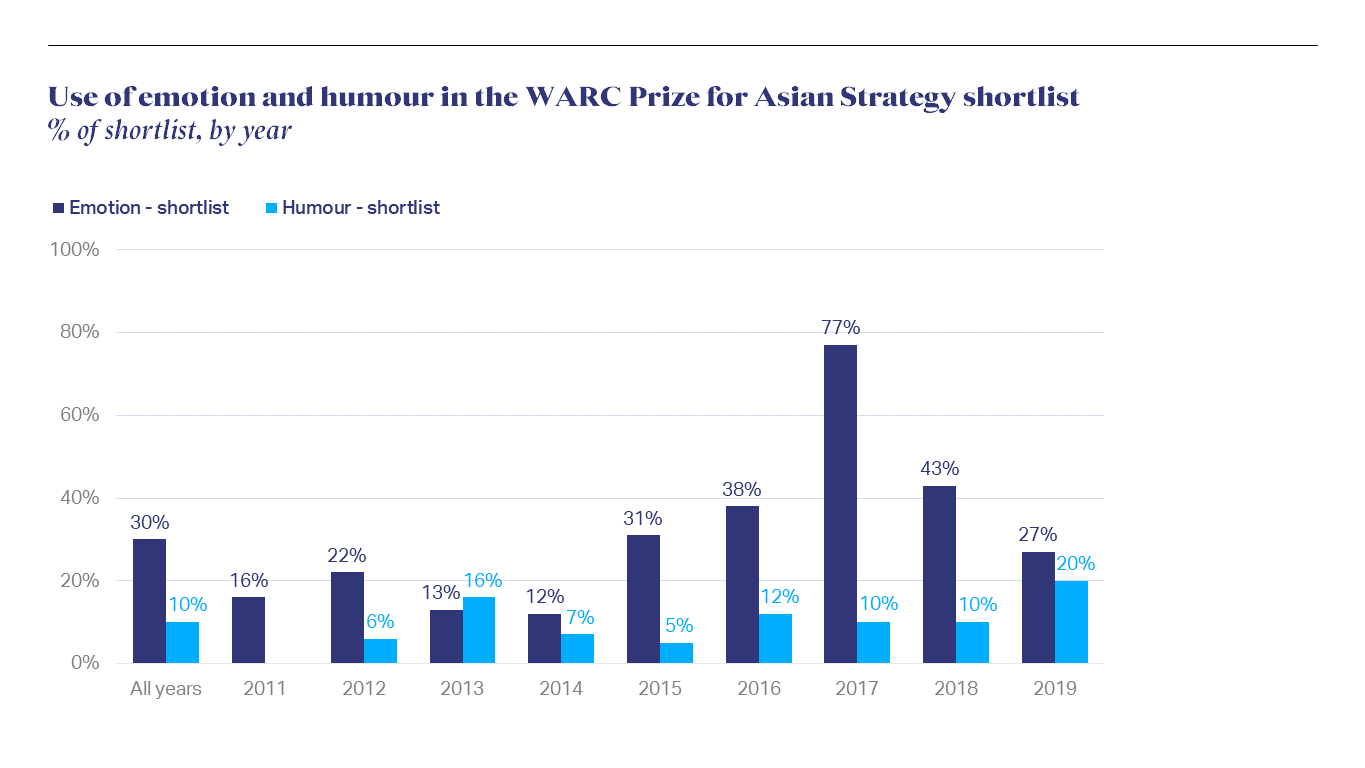

The 2017 edition of the Prize saw shortlisted campaigns that used emotion in their communications dominating at a whopping 77% compared to the use of humour, which sat at 10%. While the use of emotion was already on an upward trend since 2015, the significant jump for that year seemed an anomaly of sorts.

Which begged the question: What made 2017 so emotional? What happened that year, or more accurately, the year or two before given eligibility periods of the campaigns in consideration?

Which begged the question: What made 2017 so emotional? What happened that year, or more accurately, the year or two before given eligibility periods of the campaigns in consideration?

2017 was the year SK-II's The Marriage Market Takeover walked away with the Grand Prix, and the Prize also saw an overall rise in purpose-driven campaigns. The year prior, Ariel's Share the Load received the Grand Prix. So, one could point out that there were more emotion-led campaigns shortlisted because at that time, there was simply more emotion-led work going on in the region. But why was that the case?

Read the full 2017 Asian Strategy Report here.

Looking back a mere handful of years ago might seem a mammoth task, considering the tectonic shifts that have taken place in 2020 alone. However, strategists that WARC reached out to were game to take that walk down memory lane and offer some insights into the context behind the data.

The day after tomorrow

Bea Atienza, chief strategy officer, Dentsu Aegis Network Philippines noted that to make sense of this, we must remember that the work in 2017 was impacted by what happened in 2016.

While the coronavirus could be considered the first truly widespread shared global experience, in many ways, there was a strong undercurrent in 2016 that became a common experience across many countries, including Asia.

Didi Sutisna, also executive strategy director at TBWA\ Group Singapore pointed out at that point, the world felt more than ever polarised across many topics – gender equality, the racial divide, and the differences between the haves and haves not.

People had little reason to trust their governments and institutions, added Huiwen Tow, executive strategy director at TBWA\ Singapore. “An ex-reality TV star got appointed as the president of USA, Brexit got real, President Park Geun-Hye was impeached in S. Korea, Duterte was raging through the Philippines, the longest reigning monarch in the world King Bhumibol of Thailand passed away,” said Tow.

Atienza recalls that year as a turning point for many countries, the effects of which we’re still feeling today. “I remember that the Saturday Night Live episode that aired right after the US Presidential election that year had such a strong sense of shock and disbelief. In the Philippines, so many were incredulous after Duterte won,” she said.

A mutiny against short-termism?

Tow, who was a client-side marketer in travel tech back in 2016/2017, recalls a period characterised by short-termism.

“We were constantly sold the ‘shorter is better’ advertising narrative. Think: performance-marketing, 6 second ads, upfront-branding, click-bait titles etc. These were the years Google and Facebook were aggressively expanding their media sales departments globally and, in the region,” she recalled. “And alongside the rise of these media tech titans was the growth of tech brands that solidified growth based on promo codes and functionality, and not necessarily emotional connection.”

Advertising was losing its way, with the focus largely on identifying small smarts to trick the consumer into giving his attention in the short term, instead of creating meaningful and engaging long-term brand-building work.

“I like to think of the surge of purpose-driven/emotion-led campaigns in the 2017 WARC Strategy Awards as a counter-reaction, or almost a rebellion, against the short-termism transactional trap the industry was slowly, but surely, falling into then,” she added. “In a fast-changing and unstable world defined by bots, not people, brands seized the opportunity to be the beacon of hope to humanity, provide a voice to real human problems, and capitalise the power of emotion to catalyse real, lasting change socially and commercially. Agencies and brands were hoping to save humanity.”

The influence of the FMCG giants

Rebecca Nadilo, chief strategy officer at Wunderman Thompson Singapore believes the global shift to purpose was also shaped in part by two large advertisers – P&G and Unilever – declaring the need for their brands to have a purpose a few years prior.

“And when those big brands do, they set the tone for the industry,” she said. “It was a time where brand purpose became the buzz word of the industry and every brand was trying to define their brand purpose, so it was a matter of momentum.”

Indeed late-2016 marked the start of high-profile coverage highlighting P&G’s transformation efforts to be “a force for good and a force for growth”, while Unilever reported that in 2015, its 12 Sustainable Living brands grew 30% faster than the rest of the business while in 2016, the brands grew 40% faster and delivered nearly half of the company’s growth.

Sutisna points out that many brands at that time were becoming more conscious about the world and what people were feeling around them.

“So, there was a huge shift that many brands took, from talking about a brand purpose to brand activism. In addition to the Superbowl work by Airbnb and Audi, this was also the year of the arrival of the Fearless Girl on a global scene,” he added, with a similar shift also taking place in Asia. “SK-II, Levi’s, Vodafone, Lifebuoy, and Surf Excel were all brands that got behind a cause and had an impact or effect at scale. With work that showed a deeper local texture and relevance about women’s issues in Asia. And when you are driven by a purpose that also means that you are tapping into the emotions of your audience.”

Atienza believes that that the spike in emotional work that year also reflects what consumers were grappling with at the time, reflected in turn by brands.

“It resonated with consumers to see their favourite brands echo and reflect meaningful social issues. What’s wonderful is that the winning work that year didn’t just wallow in doubt and sadness but pushed back and gently challenged long-standing norms. Perhaps when we’re questioning the world order, we search for meaning – and what resonates with us is being able to project a world we wish we had,” she added.

What will the 2020 Prize unveil?

With the window now closed for this year’s WARC Prize for Asian Strategy, it remains to be seen what new themes will emerge from the submitted body of work now bound for consideration by the jury. Will the use of emotion and its use in articulating brand purpose or activism continue to dominate?

In looking at the chart to date, the decline in emotion-led campaigns after 2017 really stood out for Sutisna. A potential sign that the year may have just been a brief “jump on the bandwagon” reaction for many brands and agencies.

“I sincerely hope not, because the debate about equality hasn’t stopped and is not going to for the foreseeable future. #BLM is going to be the next big debate that is going to dominate the western part of our globe,” he said. “And as an industry, we can’t turn a blind eye to it. So, we need to find ways how we can join or contribute to that conversation through our own Asian lens. In a real way, not just paying lip service.”

This article is part of a special content programme marking the tenth anniversary of the WARC Prize for Asia Strategy. To read more, click here.