Customer retention

This article is part of a series of articles from the WARC Guide to customer retention.

Why it matters

Marketers often struggle to find the right balance between money spent on acquisition versus retention. The Ehrenberg Bass Institute argues that by focusing on customer acquisition to boost market share, the same tactics will help with retention.

Takeaways

- Double Jeopardy law illustrates that brands should focus on acquiring non-customers rather than increasing retention/reducing defection of current customers.

- However, tactics do not build acquisition or retention strategies in isolation. Marketing activities typically build and refresh mental availability of the brand for all category buyers (if reach allows).

- So, aim for acquisition, but understand that most tactics aimed at acquisition can also work to retain customers.

Marketing is often like buying a house – we may want a 6-bedroom mansion on the beachfront, but we can only afford a 2-bedroom apartment in the suburbs. Budget constraints mean that while we might want everything, we need to prioritise.

A common challenge for marketers is deciding how to spend their budget in order to achieve brand growth. They must decide which strategy to focus on, and then which tactics to employ to achieve strategy objectives. Generally, resources are allocated towards fulfilling two strategies: retention of current customers, or acquisition of new customers. However, the real question here is whether to balance resources equally between these two strategies (and relevant tactics), or skew resources towards one, at the expense of the other. Of course this assumes that tactics support strategies in isolation, whereas in actuality, a tactic executed to retain customers may also inadvertently acquire new customers. So which strategy do you choose?

The easier target may be presumed to be retaining your current customers. This is because these existing customers:

- Have greater mental availability: they are already familiar with your brand through direct use/experience and have established networks linked to your brand in memory. Whereas, non-buyers have less established memory networks due to their limited contact/experience with your brand.

- Are also more likely to notice any marketing or advertising efforts compared to your non-buyers. This is because non-buyers have limited mental availability and screen out your marketing efforts, and instead give attention to marketing efforts for brands they do buy.

- Have more regular touch-points with the brand such as receiving email updates, following you on social media, seeing your product in the pantry at home, which all works to remind current customers of the brand. Meanwhile, non-buyers have none of these reminders for your brand, but the equivalent reminders for other brands in the category (that they do use).

Therefore, if a brand wants to grow, it may appear that a retention strategy will be more effective. Current customers know your brand and are more likely to notice your marketing efforts. That being said, the short-term benefits from retention-based tactics may not translate into long-term success when brand growth is the objective. Retention may seem more cost-effective, especially when managing limited budgets, but does it successfully grow market share?

How brands grow – expanding the customer base or increasing current purchases?

In answering whether retention strategies grow market share, we need to revisit the fundamentals of how brands grow. Imagine that you have a marketing machine with two levers. One, when pulled, reduces the number of current customers that defect from your brand. The other lever increases the number of non-customers buying your brand. You as a marketer need to decide how much to pull each lever to drive growth.

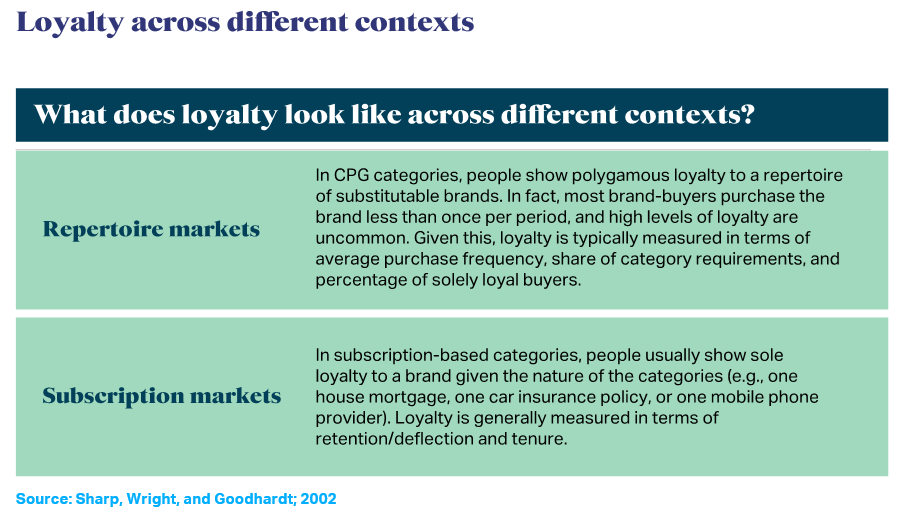

First, we need to define exactly what metrics these levers are manipulating. The lever that reduces the number of current customers that defect, or in other words, the lever to retain customers, is your ‘loyalty lever’. The type of market your brand operates in will affect what loyalty metric you are pulling (see Table 1 for how loyalty is measured across different contexts). In repertoire markets, retention generally refers to the number of brand purchases made by an individual buyer. For example, Sam purchases Brand A in the dog food category about three times every six months. Alternatively, the loyalty lever in subscription markets is reflected by the number of customers continuing to use your brand. For example, Sam renews his annual car insurance policy with Brand B (or is cross-sold another policy to cover his motor bike) rather than switching to a competitor.

The acquisition lever is your ‘penetration lever’, and reflects the number of customers your brand has, in both repertoire and subscription markets. For example, Brand A has 50% penetration if 50 out of 100 dog food buyers purchase Brand A in the given time period. Similarly, Brand B has 50% penetration if 50 out of 100 car insurance customers purchase their insurance with Brand B in a given time period.

Will acquisition or retention lead to brand growth?

To help us decide how far to pull each lever, we turn our focus to a common pattern in brand performance, Double Jeopardy. One of the empirical laws of marketing, Double Jeopardy shows that brands of differing sizes have greatly varied customer numbers, yet similar relative loyalty. It emphasises that loyalty is a function of brand size, and that it is normal for smaller brands to have fewer brand buyers who are slightly less loyal than customers of larger competitors. This pattern has been shown to hold across a wide range of categories, countries and time periods.

The implications of Double Jeopardy highlight the challenge marketers face in focusing on retention strategies for growth. This means, regardless of your brand’s size, pulling the loyalty lever more than the acquisition lever will not have a significant impact on growth. No matter how many resources you put into loyalty tactics, it is challenging to get current customers to buy more of a product/service than they need. For example, unless Sam gets another dog, you will struggle to get him to purchase more dog food than he already buys (although Rover might wish otherwise!).

On the other hand, pulling the acquisition lever all the way down is shown to be much more impactful for brand growth. Rather than encouraging current customers to purchase more from your brand, it is far easier to get non-customers to purchase you once. For instance, rather than using resources to cross-sell Sam motor bike insurance he might not need, you could instead increase your brand’s mental availability with Sally who needs to renew her car insurance policy. The key point here is that you still want to retain Sam, but your additional resources are better used to acquire Sally rather than up-sell Sam. Loyalty is still an important factor for brand growth, but it doesn’t play the largest role in increasing share. This is done by increasing penetration.

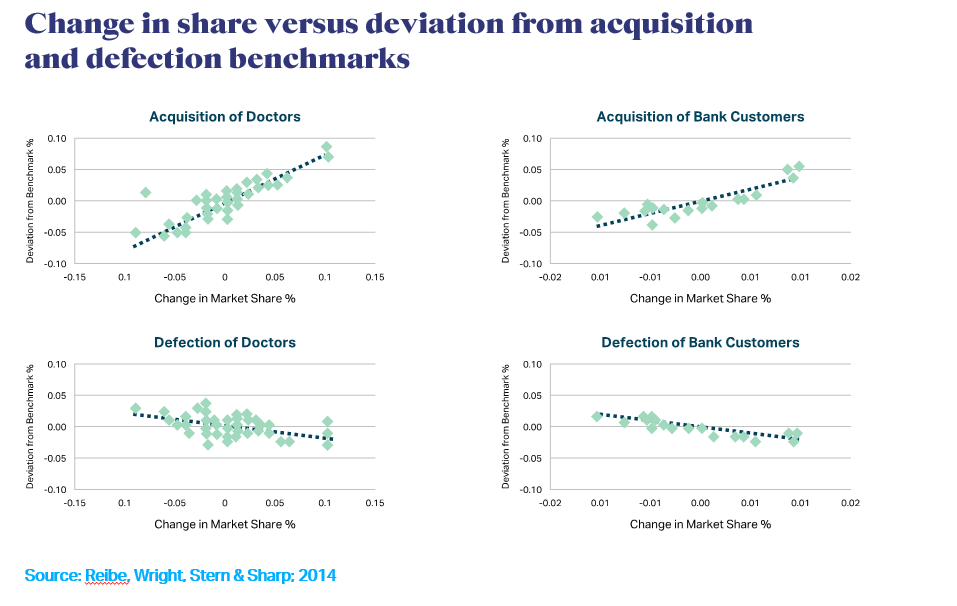

Furthermore, while Double Jeopardy is a static snapshot in time, we see the same patterns play out when we examine brands that grow or decline over time. Brands that grow do so due to greater acquisition of category buyers, rather than from reducing the defection of existing customers. Both play a part in increasing market share, but acquisition is roughly twice as important than reduced defection.

While this pattern has often been observed in packaged goods markets, we also see this in service categories (see Figure 1 from Reibe, Wright, Stern & Sharp 2014). Not only did growing brands acquire more customers than necessary to replace defections, but the flip side also showed that declining brands failed to sufficiently acquire enough category buyers to replace defections. This means retention does not help brands grow, nor does it stop brands declining. Acquisition does both.

This evidence further emphasises that marketers should not prioritise to limit defections through retention strategies, but instead should establish acquisition initiatives that encourage category buyers to purchase the brand in question. That said, keeping service levels and product quality at a reasonable level is still important so as to not upset your current customer base, but over investment in keeping these customers is unlikely to lead to significant growth. Marketing budgets are better spent when pulling the acquisition lever.

Focus resources on acquisition initiatives – and retention will follow

Focusing on retention assumes that marketers can control most of the reasons for brand defection. However, a great deal of defection/customer loss is due to factors outside of the brand’s control. For example, children start eating solid foods and therefore parents no longer need to purchase formula; people pay off their mortgages and therefore no longer need home loans; and (unfortunately) dogs pass away and therefore households no longer need to purchase Rover’s favourite dog food. Marketers really have no control over who defects and when, so it is best to encouraging new customers to fill their place.

This thinking also assumes that there are specific activities that retain customers, and specific activities that acquire customers. While you can concentrate your efforts just to reach existing customers by contacting only those on your database, most tactics that reach brand non-buyers also reach (and affect) buyers too.

Furthermore, this stems back to the principle of mental availability, which is the network of memories linked to your brand. Consumer memory plays a big part in brand choice, but also on what consumers notice and give attention to. Advertising to acquire customers is also likely to assist in retaining existing customers, and vice versa. For example, when focusing on retention, you can concentrate activities to current buyers only (such as an email database), but any external advertising activities, like TV adverts, it will reach buyers and non-buyers alike. The only difference is how receptive to the advertising these viewers are.

Existing customers may not be able to redeem a special offer for new customers only, but the exposure to the marketing activities (assuming it is well-branded) will activate the memories linked to the brand. This will work to refresh and reinforce mental availability for the brand, and ultimately increase the propensity for the brand to be noticed or thought of by your existing customers (like when Rover next runs out of doggy treats).

Therefore, while you might decide to communicate with Sally about a new car insurance policy, you are also likely reaching and reinforcing mental availability of the brand for Sam too, your existing customer. The ultimate goal is to reach all potential category buyers with marketing activities, by focusing on acquiring new customers as well as working to retain current customers.

To summarise, when the aim is to grow your brand, the evidence shows that using your limited resources to increase the number of brand buyers rather than focusing on reducing defection/increasing loyalty of current buyers (which may eventually happen anyway as your customer base grows). We might want to focus on both acquisition and retention strategies – similar to wanting a 6-bedroom mansion on the beachfront. However, we need to prioritise what we can afford and what our limited budgets allow, which is often the 2-bedroom apartment in the suburbs.

Both acquisition and retention strategies are important and are built in tandem through advertising and other marketing efforts. Therefore, our marketing efforts should be focused on an overarching acquisition strategy that aims to reach all potential category buyers.

Key references

Riebe, E, Wright, M, Stern, P & Sharp, B 2014, ‘How to grow a brand: retain or acquire customers?’, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 67, pp. 990-997.

Sharp, B, Wright, M & Goodhardt, G 2002, ‘Purchase loyalty is polarised into either repertoire or subscription patterns’, Australasian Marketing Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 7-20.

Q&A with Dr Kelly Vaughan and Alicia Barker

Read more articles from the WARC Guide to customer retention.

Search strategies for customer retention on e-commerce platforms

Danny Silverman

Are subscription services really the holy grail of e-commerce?

Danny Silverman

Customer retention with social media communities

Matthew Nolan

How to build a successful customer lifetime value program

Moises Cohen and Elizabeth Thomas

Future-proof customer loyalty programmes by driving redemptions

Natasha van der Pas