The IAB UK’s digital ad spend forecast shows a sector well placed to capture growth but also vulnerable to pullbacks, meaning the industry must look further afield for signals in the noise. WARC’s Sam Peña-Taylor takes the temperature at the report’s launch.

How do you predict the future? Arguably, the history of digital advertising has been one of systems that promise a much closer approximation of the future than what came before. Buyers could purchase outcomes; patterns of behaviour online would map future behaviour online and in the real world. Whether or not the claims made were true did little to slow the rise of digital advertising for good or for bad.

In the beginning, or the beginning according to the gospel of the IAB, which started up in the UK in 1997, the sector was worth £8m. Now, in a much more scrutinised and more mature phase, it is worth £23.5bn, according to the trade association’s digital adspend study for the 2022 financial year.

A big difference, but with an economy flatlining and an election approaching, what happened last year isn’t a reliable guide to this year.

Unveiling the report at an event at PwC’s central London offices (the professional services firm was a co-author), the 2022 figures depict shifts around some long-standing fundamentals, even in the wake of an economically complicated year.

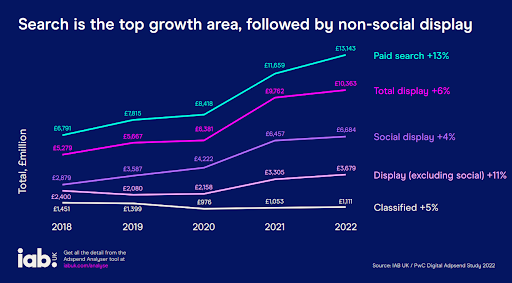

Search, for instance, having been the first truly revolutionary internet ad format – given that it wasn’t just showing people banners around websites they liked, but was actually advertising against what they were actively looking for – remains the largest channel, hoovering up 50% of UK advertising spending. This is the same share that search took in 2020 and 2021: where there’s growth, there’s a growth in search spend.

Of course, search has largely been the fiefdom of one verb-sized company, but the IAB tracks signals that this is now shifting.

It appears, for instance, that the market’s growth was more broadly shared than it has been, with the largest five companies’ growth of 9% outpaced by the rest’s 20% growth, and which together contributed to the digital market’s overall growth of 11%.

A more competitive, more diverse market is usually a good thing, and the IAB celebrates the emergence of a new (if search-adjacent) channel in the form of retail media, which for the first time in this annual report’s history is counted at £176m, with enormous potential to grow.

This speaks to a deeper trend that has fuelled the channel’s rise across the Atlantic and is now starting to bear fruit here and around Europe: that is, this has all the benefits of search advertising but is even closer to the point of purchase (even if the media buyer may have to spend with multiple providers rather than with the one behemoth).

It’s starting to show: globally, retail media is forecast to account for over a quarter of the total search market according to the latest Global Ad Trends.

Many observers tie not only the primacy of search but its new iteration on retailers’ websites to the uncertainty to come. The same IAB report now forecasts the digital advertising market to slow to 5% growth this year (which, alongside 5-6% core inflation, is not great news).

The result is that with less growth there is more competition for the existing business, and the aim of the game then becomes taking share, explains Nick Forrest, chief economist at PwC. While there is some silver lining to be found in the expectation that the economy isn’t (yet) headed for a recession of the magnitude of the 1990s or 2008, it is likely to flatline.

Specific figures aside, what should matter to marketers is that people are going to feel poorer even if the ultimate effect of the turbulence is not 2008-style waves of layoffs and consumer confidence is likely to remain subdued. It’s a tricky space in which to be setting ad budgets.

In the short term, this will set the weather for digital advertising, which is at turns blessed and cursed with far shorter lead times and spending commitments compared to some of its traditional media cousins. This means that if the tide changes, for this sector it could turn quickly. But on the converse, it’s also much more sensitive to recoveries.

This is the backdrop against which to judge the potential for a political change. Yet, a change of government won’t constitute a change of the challenges that the country and the economy face. While Labour currently appears more likely to lead the next government, it’s unlikely that there will be many radical business-facing policy changes from whichever side wins the next election, observes Lord Gavin Barwell, a former Conservative MP, turned Number 10 chief of staff under Theresa May, and now a political advisor for PwC (he makes clear that he is not expressing the firm’s opinions).

In short, it’s unlikely there will be major changes to the way business and government interact. Although Starmer’s Labour party has struggled to accommodate the business conversations that it needs to have, in Barwell’s estimation this is not an anti-business candidate.

What could constitute a change, however, is in the realm of greening the economy, even if it’s difficult to make sweeping changes when in charge of a slim majority, minority, or coalition government operating in the long shadow of inflation.

In the absence of certainty, it appears all sides – Labour, Tory, business, government – are hedging their bets while all hoping that the situation can improve soon. We all need it to.