The latest Global Ad Trends report tries to make sense of the precipitous decline in the publishing sector as a force in the advertising market.

The identity of the first printed advertisement is subject to some debate. Guinness World Records cites London title Perfect Diurnall, which started carrying book promotions at the time of the English Civil War in 1646. Others point to the Boston News-Letter, and a 1704 real estate ad for a plantation on Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Either way, the histories of the printing press and advertising are intimately intertwined. Within a century of Johann Carolus publishing what many accept to be the first printed newspaper in 1605 (the snappily-titled Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien), readers had become accustomed to seeing adverts for goods and services placed alongside editorial content.

It was a relationship that endured for centuries. Newspapers helped brands to reach audiences at scale, while advertising revenue funded the journalism that found a dedicated following among readers. Everyone was a winner.

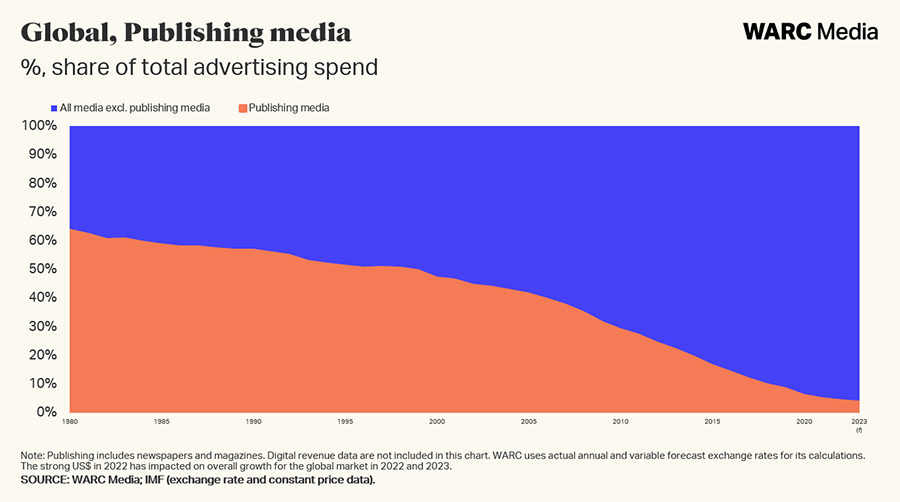

That mutual contentedness was reflected in advertising investment. In 1980, nearly two-thirds (64.2%) of all of total global ad spend by brands went to print media, according to WARC data. Two-thirds. Let that figure sink in.

While the narrative of publishing’s fall from advertising grace is well known, it can sometimes seem an older story than it really is. Newspapers would continue to occupy a greater share of spend than TV until 2001. Even in 2010, when search and social ad markets were beginning to mature, publishing media still accounted for nearly $3 in every $10 spent on advertising around the world.

Yet that decline has accelerated over the last decade. In 2007, global ad spend on newspaper print advertising peaked at $121.4bn; in 2023, investment will drop to $22.8bn, according to WARC Media forecasts.

No sign of a ‘return to quality’ in online ads

Successive industry crises – from brand safety and ad fraud to the impending demise of third-party cookies – have provided some hope of a “return to quality”, and that brands might direct greater emphasis towards premium media environments.

Marketers have made positive noises about the importance of supporting quality, independent journalism, while Big Tech firms like Alphabet and Meta – no doubt concerned about how their success may be perceived in stark contrast to the publishing sector’s plight – have launched initiatives to support journalistic media.

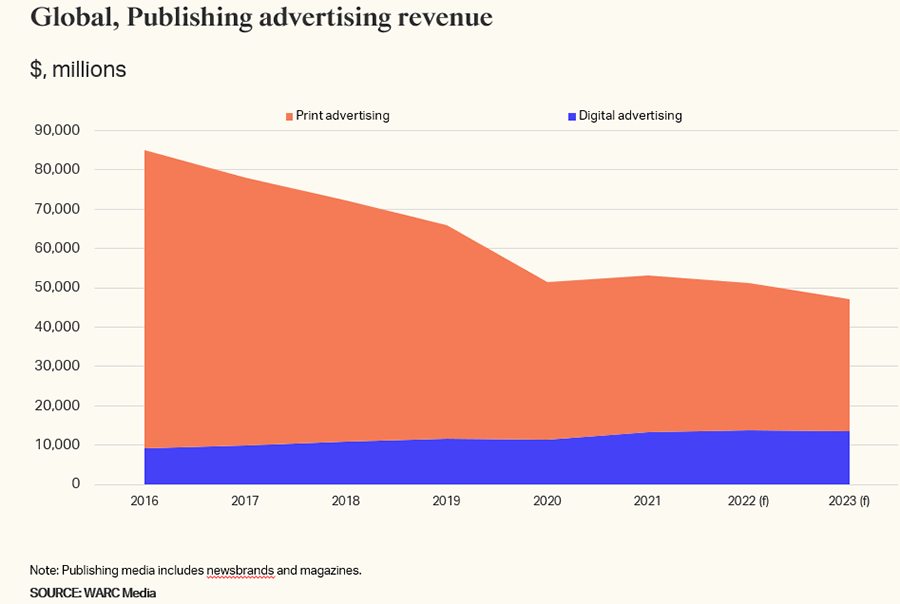

In reality, this rhetoric is yet to influence investment: publishing media (both print and digital) is forecast to see ad spend decline 7.7% year-on-year in 2023, according to WARC Media data. Amazon alone earned $37.7bn from advertising services in 2022, up 20.8% year-on-year; for context, the entire global publishing ad market will be worth $47.2bn in 2023.

On current trajectory, within a year or two, Amazon’s advertising revenue – which ultimately remains a side-hustle from its main business of e-commerce, remember – may be larger than the entire global publishing sector.

Swapping analogue dollars for digital cents

As detailed in our latest Global Ad Trends report, Media Models in Flux, the challenges facing publishers are unique to that medium.

Total spend on legacy media – i.e. video, audio, publishing and OOH – has remained largely stable in recent years, with investment switching from offline formats (such as linear TV and broadcast radio) to digital ones (CTV, music streaming, DOOH). In contrast, publishers have swapped analogue dollars for digital cents: modest increases in digital ad revenue have been insufficient to compensate for catastrophic losses in print advertising income.

This is an existential threat for a large number of publishers, according to Brian Morrissey, a media analyst and founder of The Rebooting, speaking to WARC in an interview for Global Ad Trends: “The reality of the publishing industry is that you really cannot have an original content model that is mostly or solely reliant on display advertising revenue.”

That’s not to say that publishers cannot thrive in the current market. Niche players like Politico can find a sweet spot where digital platforms are unable to cater for audience needs. The New York Times is oft-cited as the blueprint for a sustainable and scaled news business, having seen digital subscription revenue soar during the Trump presidency and COVID-19.

Yet this case study is increasingly anomalous, Morrissey argues. “There's always winners in every market. I just think, in this market, there's going be fewer winners. That's why the New York Times is brought up again and again.”

Unless advertisers resolve en masse that they are dutybound to support the journalism provided by the publishing sector – a collective epiphany that looks unlikely in the harsh economic winds of 2023 – this will leave news and magazine brands needing to carve out a share of the highly-competitive subscription economy, as well as pursuing opportunities in events and e-commerce.

For those unable to gain a foothold in the reader revenue market, all that remains is what Morrissey dubs the “Dracula strategy” – slowly draining the editorial equity through short-term monetisation measures, such as aggressive SEO optimisation of content. It is a bleak prospect, but not unfamiliar to those who read local and regional news websites.

The seventeenth century pioneers of the printed press may have been surprised to know that, as well as changing the world through the dissemination of ideas, their decision to include advertising would revolutionise consumer capitalism for ever. It is worth reflecting on this lasting legacy, as the sun appears to set on a 350-year-old business model.