Marketers are obsessed with brand purpose, but what we really need to be obsessed with is finding ways to grow businesses and brands in a sustainable and ethical way, argues Florencia Lujani strategy director and cultural insight expert at Media Bounty.

Economics is the mother tongue of public policy, the language of public life, and the mindset that shapes society. - Kate Rowarth, ‘Doughnut Economics’

Growth is at the centre of every client brief I’ve ever worked on: increase sales volume, penetration, frequency of purchase, market share, and a long list of other etc. The economic system prioritises growth, so it’s the standard that structures our social life (our relationships, personal goals, etc), culture (our language, creativity, etc), media (news, editorial, etc) and so much more. As the status quo, the ‘common sense’, it tells us that prosperity is *only* possible with growth.

I think last year it came to a point where I started looking at these briefs with a somewhat sceptical eye, imagining what they could look like if they had different objectives.

Growthmania

Businesses (and the brands we do creative work for) keep the economy going: they invest, employ, and get people to earn and spend more. Their products and services improve our lives and help millions of people escape deprivation, and we are instrumental in shaping choice, providing comfort and helping people make sense of the world.

But global economic development has also fuelled a dramatic increase in our use of Earth’s resources. Our lifestyle (and by *our* I mean, the lifestyle of the middle-class in developed countries, this is a completely different story in developing countries) is based on perpetual extraction and accumulation. And this comes with two opposing effects: In 2020 many big companies have had a stellar performance, producing and selling more than ever, reaching all-time high stock value and market valuation. At the same time, the impact of COVID-19 on people’s livelihood and wallets can’t be understated. All the wonderful and positive social and environmental reckoning was short-lived because we had to deal with loss in every sense of the word, brand purpose didn’t capture anyone’s attention, and the pandemic became a powerful vector for upward redistribution and increasing inequality.

While the crisis is ongoing and we’re still living through trauma, all the focus is in growth and recovery. I’m sure that most (if not all) of the businesses that last year enjoyed a fantastic performance, will raise the bar and aim to improve (or at least sustain) those numbers in 2021. Regardless of what that means in terms of resources and people’s wellbeing, shareholders still want to see YoY gains in the finance charts.

Anyone who’s sat in planning meetings has seen that Einstein quote about how important is to spend most of the time identifying the right problem to come up with the right solution.

So I’m asking, is this the right answer to the right problem? Is perpetual growth attainable, helpful or even responsible? I’m not the only sceptical one: there are many economists also putting forward ideas based on prosperity without growth.

(Copyright: Julien Pacaud, 2010)

Creative destruction

Classical economists like Adam Smith acknowledged the existence of natural limits to growth and established that infinite economic expansion for its own sake wasn’t going to be possible or desirable. But then neoliberalism took the reigns, and Joseph Schumpeter coined the term ‘creative destruction’. It illustrates how businesses engage in a process of destruction of the old, replacing old systems with new ones that allow them to see bigger profits.

Growth and employment are directly related. In ‘Elements of Ecological Economics’, Andersson and Eriksson explain that if GDP grows less than 3% the rate of unemployment increases. So as a consequence of this, 3% has been established as the “normal” or “natural” growth rate (The Bank of England shows that on average, the economy has grown by 2.6% per year since 1949)

But a continuous, non-stop growth at 3% would require a degree of violence on our Earth that would result in an ecological systems breakdown within the next 100 years. Jason Hickel in ‘Less is More’ (2020) puts it in tangible terms:

The current system requires annual growth of roughly 3% to avoid the shock of recession. This means doubling the size of the economy every 23 years. The economy of 2000 must be 20 times larger in the year 2100, and 370 times larger in the year 2200. Yet 2000 was the first year that humanity used more energy and materials than the safe limit.

Just try to picture it.

What does an economy 20 times larger than today’s look like?

Growing businesses in the 21st century can’t be done at the expense of destroying wellbeing and the planet. The way we do business needs to be aligned with the social and ecological impact of the next 100 years.

We need to start designing businesses for permanence, not performance.

(Copyright: Eugenia Loli, 2015)

Changing the question

To design businesses for permanence and not performance, we need to go back to my original question – is perpetual growth, extraction and accumulation, the right answer to solve the problems that we have in hand? How can businesses solve problems and thrive without ‘creative destruction’?

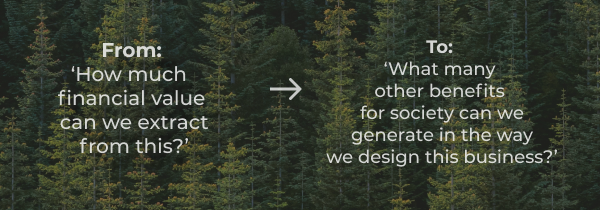

Kate Rowarth, author of ‘Doughnut Economics’ (2017) says that the question driving economic activity needs to change:

She rightly points out that one question is extractive, the other generative.

But for the question to change, we need a reckoning from the CFO and CEO (for starters, then from board members and so on), and as an industry, we also need to adopt a macro view.

We’re busy rewriting brand purpose when we need to look at the whole economic and environmental impact of brands.

We’re busy building sustainability programmes when supply chain teams are negotiating contracts with sweatshops in developing countries.

We’re busy creating social media posts in support of social causes when in the boardroom the question is always about getting higher returns, quicker.

People will still need to buy products, and we can keep on meeting that demand with really effective creative work, but we have so much talent for ideas it would be a waste not to get involved. Let’s remember the current system was never supposed to stick around for this long (unfortunately, this quote includes the C-word, no, not that one).

“It is the very speed of the change, the very instability of capitalism, that reveals it to be a transition. It is so clear now, given so much change, that it is not a steady way in which the economy operates in a particular repeated manner (…) To understand why it’s a change, a turmoil, not an epoch, just look at how fast life under capitalism has, until recently, been continually transformed.” - Danny Dorling, ‘Slowndown’

Let’s all stop acting all ‘strong and stable’ in the rat race of growth.

It’s encouraging to see some great industry thinking aligned with this.

- Omar El-Gammal’s essay for the IPA Excellence Diploma ‘An Evolution of Weeds and Trees: Reimagining Brand Growth in the 21st Century’ suggested we ‘think of growth in context of how it shapes society and the environment’. It’s a fantastic essay, a personal favourite.

- Shots magazine recently published an article with Tobey Duncan from Uncommon about “moving the bottom line from being about finance to focusing on ethics”.

- Jake Dubbins (MD of Media Bounty and Conscious Advertising Network) shared with me this framework for measuring the carbon impact of advertising presented at EffWorks.

- Purpose Disruptors are trying to get the advertising industry to help tackle climate change.

Further reading

- ‘Less is More’, by Jason Hickel, looks at the relationship between growth and prosperity from an anthropological perspective

- ‘The Case for the Green New Deal’, by Ann Pettifor, looks at the political reorganisation of the financial system at a global level

- ‘Doughnut Economics’, by Kate Raworth, rethinks economics so that it’s suited for the challenges of the 21st century and not a discipline based on models from the 1800s

- ‘Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration’, by Danny Dorling, looks at it from a geographical and historical perspective

- ‘Elements of Ecological Economics’ by Jan Otto Andersson and Ralf Eriksson, looks at an economic model that incorporates justice, sustainability and prosperity