Uncommon Kind’s Jenn Chin and Caroline Wang say representation in advertising matters because people’s stories and lives matter, and because representation is important for brand success and business growth, which can be quantified in percentages and statistics.

Purpose Incorporated: A primer for brands in APAC

This article is part of a special series on how brands in APAC can go beyond profit to do good and do better for themselves and others. Read more.

Non-WARC subscribers can read this series in its entirety by accessing the articles via the landing page.

As two Asian women living and working in Australia, one of the first things we do when scoping new opportunities is to do the LinkedIn and “About us” page scan for employees who look like us.

This experience isn’t unique to us – it’s an almost universal practice among marginalised and under-represented groups in Western markets. Doing the LinkedIn and “About us” page stalk is like a quality assurance check to evaluate whether the brand or supplier shares our values and whether we, as women of colour, would be valued, heard and respected in return.

On a superficial level, the diversity, or lack thereof, in company headshots can quickly undermine or support a brand’s diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) claims on its website.

As Asian women, representation matters in our professional lives because it’s a heuristic for a company’s DEI values and commitment. But as consumers, representation in advertising matters because it tells us that our stories matter and our lives matter. Seeing ourselves reflected on screen, after being invisible, forgotten or caricatures for so long, is a watershed moment. You don’t realise how powerful it is to see someone who looks and lives like you on screen, within a company, on a conference panel until it happens.

The past few years have shown the importance of representation for brand success and business growth, quantified in percentages and statistics. But as advertisers, marketers and brand managers, we need to remember to take a step back and evaluate the human impact of our work.

When it comes to representation:

1. Brands don’t reflect the world to us. They actively construct narratives that influence how people feel about themselves and others.

Media, advertisers and brands are cultural architects. Advertising, like all media, has the power to create and reaffirm enduring stereotypes, reinforce dominant (white) narratives and fortify Eurocentric beauty standards. But what’s the real impact of this?

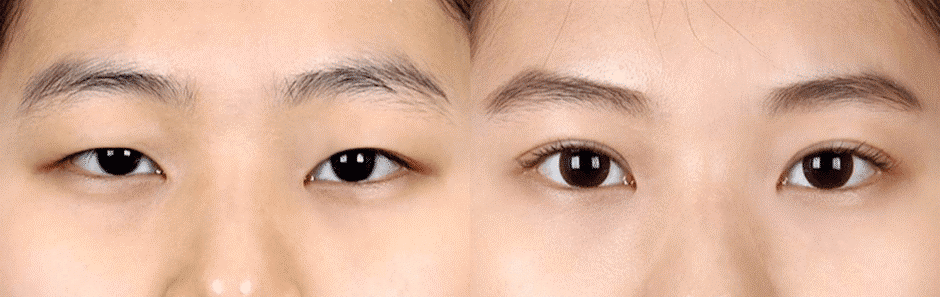

As Asian women in Australia, strangers verbally harass us using racial epithets from popular culture. Colourism is still rife in nearly all regions of Asia, propped up by Eurocentric beauty standards, and plastic surgery to obtain “double lids” is becoming a rite of passage for young Korean women.

In Todd Sampson’s latest documentary Mirror, Mirror, which explores the impact of advertising and social media on body image, a 72-year-old woman is preparing to undergo a facelift procedure.

She woman looks down the barrel of the camera and says, “Society doesn’t make room for women over 70… they just disappear.”

And the data supports this. Kantar’s Global Link platform shows only 6% of ads show people aged 65+ worldwide (Kantar, Global Monitor, 2021). In APAC, a 2018 study led by Unilever showed only 3% of ads in Asia featured women over 40 years old.

By keeping our lives and lived experiences invisible, we let long-standing, dominant Western narratives prevail. There has been a long history of state-sanctioned discrimination against Asians in Western markets, which has undermined our right to self-representation, barred us from public spaces and influenced how others (mis)treat us. In a COVID-19 world, we’re seeing the resurgence of anti-Asian sentiment, fear mongering and the rise of hate crimes against Asian communities in the West. There are tangible, everyday harms (street harassment, the Atlanta spa shooting, the very existence of a #StopAsianHate hashtag) from inadequate and a lack of representation.

We urgently need counter-perspectives that show us as complex human beings and our heterogeneous communities.

2. Overtly tackling stereotypes in brand campaigns and taking a political stance is one route but there is power in normalising our everyday lives.

In APAC, global and local brands are taking overt stances on social, political and environment issues.

While stories of adversity and struggle resonate with broader audiences, not just those from underrepresented groups, we are more than just “coming out” stories, racist incidents and micro-aggressions. “Slice of life” stories can be just as powerful because they validate our right to exist mundanely and live “just like everyone else”: to do our laundry, shop for groceries and buy fast food.

Inclusive representation in slice of life advertising doesn’t reduce us to a spectacle or a story of injustice and triumph. We’re not just fodder to elicit empathy or an unjust story to be consumed.

P&G brand Pantene launched #PrideHair in 2020 to raise awareness around the challenges for LGBTQ+ job seekers.

Pantene, #PrideHair brand video, 2020 and Pantene, NEW Pantene Micellar Water, 15” retail, 2021

While #PrideHair is one of Pantene’s landmark brand campaigns, Pantene casts transgender models in 2021 retail spots to show their commitment goes beyond a campaign cycle.

Inclusive casting is a step closer to a richer tapestry of stories and voices from marginalised communities, one that captures holistic and layered representations. It takes time for brands to reach that complexity and breadth of storytelling but we need to start somewhere.

3. Presence alone isn’t enough. Brands needs to start creating stories that put our experiences at the centre of the narrative.

“There is a clear omission by marketers in how they market to black audiences. Their approach has been, for years, to build brands for white people first and then figure out how to adapt and talk to other markets later.” – Keith Cartwright, creator of P&G’s “The Look” (WARC Guide to Brand Activism).

“The Look” demonstrates the power of crafting brand messages and stories that speak directly to under-represented audiences. There is appetite and resonance in creating stories with marginal groups in mind first, instead of an afterthought.

Google Australia, “Helping you help them”(2021) shows how search helps a father, from a migrant background and with limited English proficiency, introduce his daughter to Australian football. Google’s ad taps into the universal truth of parental care and guidance but the story is uniquely a migrant story.

Watching the father in the Google ad reminded us of our migrant parents using search to translate English into their native languages. Or the times where we, or our parents, have misused colloquialisms because we don’t have a generational grasp of the English language.

Google’s brand story appeals to broader audiences – we can all relate to feeling lonely and isolated at some point in our lives. But what makes the ad especially resonant for us has little to do with the ad’s objective quality and everything to do with our orientation as first-generation Australians and being children of Asian immigrants. Google speaks directly to us, making us feel seen and heard first.

Remembering the “why” and “who” behind calls for representation

Our experiences differ from Asian consumers who grew up in Asia. This disparity highlights the constructed and discursive nature of race and social categories but also their inherent malleability. If popular representations had the power to create and reinforce reductive narratives about us in Western markets, then representation has the power to correct those narratives and forge new ones.

Which means representation commitments in DEI programs are essential. The stakes for more inclusive representation in popular culture, leadership teams and expert panels are higher. Why calls to diversify stories, casting and creative directors in advertising are not trends or some abstract “consumer data” but a legitimate catalyst for behaviour and attitude change towards marginalised communities.

We are two Asian women, born a generation apart, but Asian representation has shifted marginally in the 20 years that separate us. The same submissive, docile, objectifying and orientalist fantasies persist, which have pervaded both our personal and professional relationships. We’ve been astounded, angered and dispirited by the similarities in our experiences.

This WARC series is both a privilege and a platform. After being invisible for most of our lives, we’re not comfortable being visible but we recognise the power in using our expertise, lived experience and visibility to pave the way for those who come after us. We can’t wait for others to lift us up but we do need those in power to willingly make room at the table and hand over the mic.

We acknowledge that #BlackLivesMatter worldwide and First Nations movements in Australia have brought conversations of racial inequity into global consciousness. Without them, we would not have the vocabulary, theories and frameworks to talk about representation.