Farm Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EJ, UK

Tel: +44 (0)1491 411000 Web: www.warc.com

| Published by World Advertising Research Center Ltd Farm Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EJ, UK Tel: +44 (0)1491 411000 Web: www.warc.com | September 2008 |

James Aitchison and Geoffrey Precourt, of WARC Online, discover how brands can take advantage of societal change and how Philips and Henkel use co-creation and hear about Coca-Cola’s corporate responsibility strategy.

This is one of a series of edited extracts from the ESOMAR 2008 Annual Congress in Montreal. Other articles cover:

For WARC’s full coverage of ESOMAR 08 visit our conference blog page.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

ESOMAR’s 61st Congress – the first on non-European soil – opened with a jazz fanfare and five-minute acrobatics display. We are in Montreal, after all, home of the eponymous jazz festival and international circus phenomenon, Cirque du Soleil.

But the volley of opening words from ESOMAR’s various great and good touched on the less celebratory crisis that is engulfing world financial markets. No one offered an opinion as to how this might affect market research, but for a conference styling itself around the theme of frontiers, it seems that there’s a whole new one looming on the horizon.

How brands can benefit from change

The presentation from German research organisation GIM looked at how brands in western markets could predict and benefit from societal change and, in particular, changing values. It is through shared values, the presenters argued, that brands and consumers connect and interact.

Using the Delphi-Method, which aggregates and analyses the output from experts and futurologists, the presenters highlighted a key macro-trend in all western societies: a deepening social divide between rich and poor, with the middle classes squeezed in the middle. It is caused, they said, by the transition to a knowledge economy in which the educated rich benefit and the poor lose out, as industrial jobs move to other (cheaper) parts of the world.

The effects of this divide are threefold:

1. At the wealthy end of the spectrum, there is more luxury and conspicuous consumption, combined with a holistic view of health and the benefits of leading a healthy lifestyle. This is the secure enclave of the rich.

2. At the poor end, there is more “discount consumption”, an increase in unhealthy lifestyles and a growth in its negative consequences, such as obesity. This is the reality for the poor.

3. For the transient middle classes, life is less certain, with their consumption and overall health determined by their volatile socioeconomic status.

The middle classes that populate this aspirational yet uncertain segment of society will adopt several coping strategies in response to their uncertain future, all of which hold opportunities for brands:

1. Embedded individuality – there will be less uncompromising individualism, and more framing of individual needs and goals in a social context. Society will move to a “mature form of hedonism”, not so self-oriented. Brands should therefore aim to support and tap into social rituals.

2. There will be a move from “work vs life” to a more complex “multi-duty” life, which includes a myriad of duties such as children’s education, pensions and health. “Post-material goes functional”, the presenters said, as people become “entrepreneurs of their own life”. For brands, there will be an increasing demand for products that simplify multi-tasking and help consumers handle busy schedules.

3. Engaging in the sane society - sustainability and social responsibility will become key drivers and motivators for middle class consumers. So brands that can demonstrate sustainability and ethical credentials will be in demand.

One love, one brand?

Is the world really flat? That was the question asked by a presentation from Unilever Thailand and Flamingo Singapore, which tested the notion of the three-time Pulitzer-winner Thomas Friedman that technology and globalisation had essentially rendered consumer wants and needs the same the world over.

Using the universal concepts of love and romance, the presenters argued that there were enduring human values that defied culture and geography, but they often had nuanced expressions at a local level. For example, the way that love and romance expresses itself is very much driven by the status of women in a specific society.

For global advertisers, the challenge is to tap into these global values but given them a local interpretation. Or, in the words of Friedman, they need to “glocalize” their strategy.

Brands and the megacity

There are now seven cities in the world that have an urban sprawl encompassing more than 20 million people; 18 that have ten million and 49 that have five million. They represent a long-standing tradition of urban growth that some say began in 130BC when ancient Rome became the first city of one million people.

And it’s this growth, argued GfK Roper’s Nick Chiarelli, that has led to many of the major innovations and developments in human history, whether it’s the legacy of the Romans or of the Victorians.

Fast forward to the present day and it’s still these urban environments that are the birthplace of many new innovations to meet consumer requirements. Before you get excited, bear in mind that most of the lower needs in Maslow’s hierarchy have already been met. So the examples he unveiled were brands spotting the niche requirements of the modern urban consumer.

Take, for example, the US-based FlexPetz, which in the company’s own words “is a unique concept for dog lovers who are unable to own a full-time doggy pal, but miss spending time with a canine friend”. And perhaps less controversially, there is Velib. Unlike renting pets, this enables Parisians to hire and return bicycles from a network of depots around their city.

The co-creators of innovation: Philips and Henkel

It’s well known that a recent trend in NPD has been to involve consumers in the innovation process. But if the presentations from Philips and Henkel’s are representative of the whole, consumers are now feeding into the very earliest stages.

First up, we heard how Philips took the decision last year “to hardwire consumers into the centre of its innovation process.” And it did so using web 2.0 technology to create the Philips Sensorium Community – a private online network of technologically interested and savvy consumers from the US and five European markets to input into the company’s product development, from supplying ideas right through to feeding back on marketing communications material.

Philips is able to tap into this resource in a variety of ways, ranging from observation of the network through to direct, one-to-one chats with specific individuals. An example that was shared showed a series of videos that panel members had uploaded in response to an invitation from Philips to tell them what pieces of technology would make their lives easier.

The case from Henkel explained how the German manufacturer sought to generate ideas for new areas and opportunities for its delicate fabric detergent brand, known as Perwoll in Germany and Perlana in France and Spain.

It chose a very different medium to Philips – a face-to-face, two-day workshop with the international brand teams, representative consumers, fashion experts and graphic designers – but generated over 250 possible new brand ideas from which they converted 12 into written up concepts to pursue.

Coca-Cola’s Management of Its Brand Equity

Once upon a pre-digital time, corporate social responsibility (CSR) was a reactive impulse. Companies that had reason to be concerned about their corporate reputation – particularly those enterprises facing regulatory risk or those with near monopoly status – needed to step up and re-introduce themselves to consumers with their brightest face.

That all changed with the introduction of the internet and the empowerment of consumers who suddenly had new easy access to the behavior of all kinds of companies.

If they liked what they saw, they often voted with their pocketbooks. If they didn’t, they realized they had the power to spread the word and boycott a variety of products and services.

And the nature of CSR changed forever. The proliferation of easily accessible information about companies has increased the importance of CSR to average consumers and thus to a much wider spectrum of companies.

These companies now face demand-side pressure with consumers potentially being unwilling to purchase their products, or boycotts if they fail to address CSR issues.

“There is no doubt that corporations want to inform the world of their good citizenship, but what CSR assets are the most effective and how and where is the message best conveyed?” asked David Pring, EVP/Ipsos Insight US Products.

“In the past, marketers had worried less about the collateral impact that one brand in their portfolio might have on another. Now with the internet, word-of-mouth and other forms of communications, they know that consumers understand the linkage between brands and also their corporate parents. With iconic brands such as Nike and Apple they are inseparable. With ConAgra, by contrast, there’s little linkage between its brands in more than 100 countries and their corporate ownership. By contrast, Unilever’s ‘vitality’ strategy set out to bring its corporate identify to the consumer’s attention.”

Coca-Cola’s brand has a consumer perception much like Apple’s in that it “represents arguably the world’s most recognized name, logo, and the strongest equity,” said Angela Lovejoy, who has global responsibility for sparkling brands and corporate brand market research at the Coca-Cola Co. “However the linkage with the company’s other major non-alcoholic beverage brands such as Fanta and Sprite – not to mention some 450 other brands that span 200 countries – is more tenuous among consumers.”

In recent years, Coca-Cola’s CSR initiatives have included investments of some $100 million in community programs, including environmental stewardship, HIV/ AIDS, disaster relief, physical education, and education.

More specific to the company’s most visible products, the company also has goal of returning all the water it uses for its beverages back to nature as well as improving the environmental efficiency of its packaging. And one of its most endearing advertising icons, the polar bear, pointed the organization to the Polar Bear Support Fund.

“Most of these CSR initiatives have not been actively conveyed directly to the consumer,” Lovejoy allowed. “Our dilemma at Coca-Cola was how to most effectively deploy and convey corporate CSR initiatives to the global consumer.

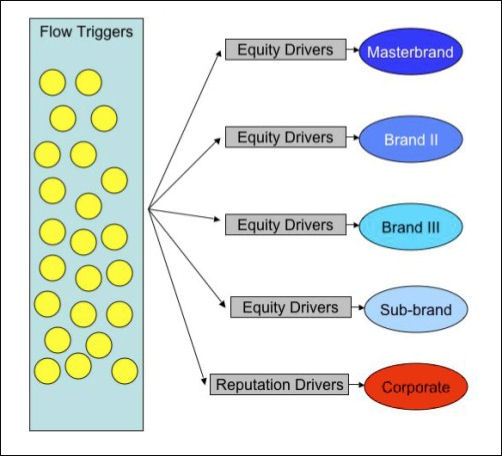

“We needed to understand how equity flows between key Coca-Cola brands and the company itself; we needed to develop a purpose-driven brand portfolio that would link the brands and the socio-environment agenda under one company strategy. We needed to discover which consumers were most influenced by CSR, what platforms and triggers would be most effective among what societal groups, and what would be the impact of specific CSR programs on each brand’s equity and the overall Coca-Cola reputation?”

For Coca-Cola, CSR needed to be anchored in equity flow. Said Pring: “We applied the definition of ‘the process of change in the value perception of a brand, or brand(s), including the total franchise brand, from the consumer perspective due to direct or indirect brand-related activity.’ ”

CSR initiatives would become indirect brand-related activity, with an effect not only on the equity of that brand, but on related entities, other brands or the body corporate. The adage that “bad news travels fast” carried the implicit assumption that flow could be negative or positive. (Witness chaos in the airline industry or the negative sales consequences of shoddy Chinese toy-manufacturing processes.) It could move from one Coke brand to another. Or, the flow could be compromised – even enhanced – by brand confusion.

“The connection could come from the visible linkage provided by The Coca-Cola Company logo on many of the packs, albeit relatively small in most cases,” Pring continued. “Linkage could also be derived from other sources ranging from publicity to word-of-mouth…. All flows of equity are not equal. Flow can be as a result of various conditions, accidental, incidental and created.”

The mix of CSR triggers can be external and internal – among them, advertising, promotions, the link between the brand and the initiative (i.e. recycling water used in product creation back to nature), and news stories. The bottom line, according to Lovejoy: “to benefit society as well as provide competitive advantage to Coca-Cola”.

To track equity flow, Coca-Cola began to experiment with data from Global Reputation and Drivers Evaluation (GRADE) by the Ipsos Public Affairs Division, with emphasis on three components - direction of the flow, the brand orientation/loyalty segments, and the magnitude of the flow – while focusing on five generalized dimensions – familiarity, uniqueness, relevance, popularity, and quality.

To use GRADE globally, the company selected six representative companies from its international shelves, said Pring, “to focus on refining the equity transfer understanding, particularly from brand to brand, as well as determining the program optimization against target segments.”

Countries participating in the research were divided into two sections: Group 1 countries, with high loyalty to Coca-Cola, but not as much concern for environmental issues; Group 2 countries, which seemed to have high interest in social responsibility, but not as much connection with the brand.

The result – from both sectors – was that CSR initiatives do work in triggering equity flow: “In both groups, we had a good lift for the impacts on the brand equity and corporate reputation drivers” Pring said. “These generalized results provide a guide for how we are using the more granular country-specific information and how the application will differ by the level of caring in each country.”

Group 1 countries, already loyal to the brand, did register upticks in brand equity and corporate reputation drivers. But, in Group 2, where sales increases were comparable to Group 1, the CSR programs had a greater impact: Future initiatives, the research showed, can maximize performance in the context of those markets.

For Lovejoy, from the broader perspective of the efficacy of the equity-transfer program, the CSR study demonstrated five positive attributes: it defined target groups for future programs, it helped determine strategic priorities, it established the potential business impact of CSR programs and, perhaps most importantly, represented a corporate shift from a static to a more active brand community.

| James Aitchison is the managing editor of WARC Online.

|

| Geoffrey Precourt is the US Editor of WARC Online.

You can read their reports from ESOMAR 2008 Congress and other recent marketing events here. |

http://www.warc.com | © World Advertising Research Center Ltd |