Navigating the polarized political landscape in the US is no easy feat, but WARC's Cathy Taylor offers some key themes in her introduction to a deep dive on how brands can meet these challenges.

This article is part of the January 2021 US Spotlight series, “Marketing in a polarized nation.” Read more

Even though it was originally said years ago, this quote by the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan made a comeback during the Trump years: “You are entitled to your opinion. You are not entitled to your own facts.”

As the US welcomes a new president, the problem – and a lot of the polarization – has to do with the fact that the atmosphere of non-stop punditry and algorithm-heavy social media platforms have led many Americans over the last few years to think the aphorism is not true, that they are, indeed, entitled to their own facts.

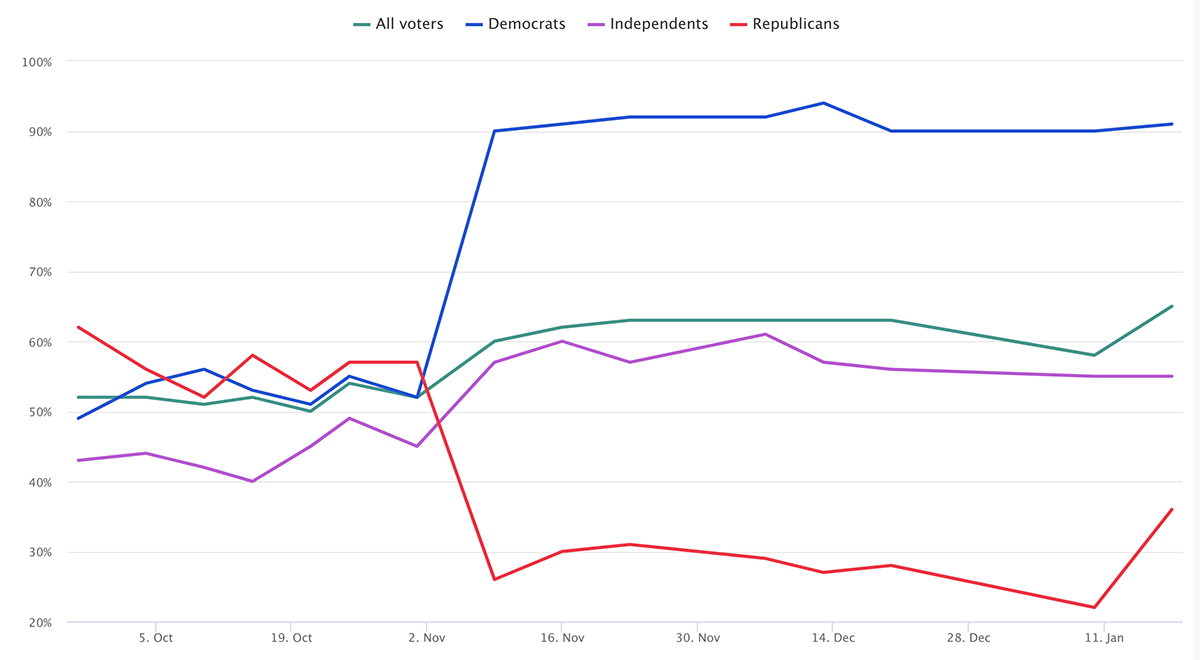

Case in point – the “fact” that the presidential election was not free and fair. Even though election officials and judges across the country – Republican and Democrat – certified that it was, and that Joe Biden was handily elected President, most Republicans, conditioned by two months of assertions by President Trump that the election was “rigged” believe it to be so. According to Morning Consult, one of the contributors to this first US Spotlight report, trust in elections declined from 72% in September 2020 to just 27% in early January. During the same time frame, Democrats’ trust in elections rose from 62% to 79%.

Decline in trust

But perhaps even more interesting is when the steep decline in trust occurred for Republicans. It began on Oct. 25, as early voting, which tends to lean Democrat, was in full swing, and the precipitous decline continued through Nov. 9, some two days after Joe Biden was declared winner. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, is it possible that those who lost confidence in elections had trouble believing their candidate had lost? And thus cherrypicked the “facts” that suited them? Would the same have been true of those who voted for Biden if he had lost the election? The upswing in Democratic trust also coincides with the election result.

That encapsulates where the US is as a nation – we are a nation that cannot agree on its own facts. And even as most brands would prefer to sidestep politics, it creates a conundrum. If we can’t agree on who won the election, or how real the pandemic is, or the origins of climate change, or if systemic racism is a, well, fact, how can brands reach customers with such varying beliefs and attitudes? Or should they try to navigate it at all?

This becomes particularly difficult at a time when brand purpose reaches for lofty heights. It’s rare to find a major brand without a diversity and inclusion officer, or a sustainability program. That said, even as most major brands address societal issues, their levels of commitment are variable. There is still much that separates Ben & Jerry’s from General Motors.

In the seven pieces for this report, no easy answers will be found – and yet, some themes emerge.

1. Protection from disruption

One key theme is that even in voting for different candidates, we were searching for the same thing. According to an article by Kantar Chief Knowledge Officer J. Walker Smith, what everyone is looking for is protection from disruption, the main dividing line being your perception on how to get that protection. For Trump voters, it meant a continuation of the same administration and policies of the last four years; for Biden voters, it meant returning to a more recognizable (and calmer) form of governing. What brands need to do, by extension, is help ameliorate these feelings of constant disruption that go as far back as 9/11.

The interview with the long-time political pollster Mark Penn says that the electorate is more moderate than one might think. Though that interview was conducted before the Capitol riots – which show our partisan divide at its ugliest -- his analysis is that we are actually more moderate than people think, with roughly a third of voters being either conservative or moderate and a quarter being liberal.

2. Trusted experts are the new Influencers

The nature of influencers is changing, as people seek truth. We Are Social says that today’s influencers are valued for expertise and what they stand for – gone are the days when influencer content was about shopping sprees. The new influencers are either people who have converted their platforms to deliver facts, or a new breed, like Dr. Anthony Fauci. The 80-year-old Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984, has been such a credible voice during the pandemic that some new pet owners have named their pets after him.

3. Corporations have more trust than government

But Dr. Fauci may be that rare government official who has so much trust. Increasingly – and this creates one opportunity for brands – consumers trust corporations more. According to an article for this report from Victoria Sakal at Morning Consult, a growing share of Americans (31%) feel corporations should use their influence to impact important issues. That’s not a majority, but it is also a 63 percent increase from August 2019.

And yet, the crux of the problem is not whether brands respond to the current times, but how. The first two weeks of January in the US were jarring in a way that many have likened only to 9/11, a moment that ruptured the nation’s narrative in ways that may have been signaled before, but became much clearer when they culminated in a horrifying event. The response from many prominent brands was to pull political contributions from those in office who sought to undermine the results of the election.

4. Provide sanctuary

Another is a more low-key route, of providing not only trust and truth, but even sanctuary. As Anita Schillhorn of McKinney emphasizes in her article: “Even if brands don’t overtly message about unity in the face of partisanship, there are many actions they can take to change the misinformation landscape and support democratic principles. And, as people continue to face the anxiety of witnessing an insurgency on top of the pandemic and other stressors, brands can play a role in providing a little respite.”

5. Brand media decisions matter

For all the work brands do to espouse certain values, it can all be undercut by not paying attention to where they show up in media. The great de-platforming of ex-President Trump – and the roadblocks put in front of alt-right platforms such as Parler – don’t take away the risk. As Avin Narasimhan, US Head of Communications Planning at PHD notes in his piece on the necessity of brand values: “Of course, all the effort committed to believing and being can be undermined if your brand shows up in the wrong place – which is why media accountability and transparency is essential to values-centric marketing.”

6. Embracing polarization makes it clear what a brand stands for

For most brands, polarization is a terrifying thing, but some argue that it shouldn’t be. An OpEd from Kirsten Maryott of Wieden + Kennedy argues for polarization. As she says, “Polarization – in politics and beyond – gives us passion groups. Gives us friction. Friction creates cultural heat. Cultural heat creates buzz. And when you can tap into that, suddenly your brand isn’t invisible. When it’s clear what a brand stands for, and what they stand against, things get interesting.”

But if that’s still scary, a return to the Morning Consult data may help – it indicates that what people may really want right now is calm. Despite their distrust in the election, 54 percent of Republicans said they wanted Trump to concede, a signal, perhaps, that moving on from the election, and the riots, is the ultimate protection from disruption.

Read more in this Spotlight series

Polarization – why, for brands, it’s a good thing

Kirstie Maryott

US consumers voted for stability over disruption, and that has implications for brands

J. Walker Smith

Brands should have values, not politics

Avin Narasimhan