Thinking in three dimensions: How businesses can maximise profits and be a force for social good

Mike Follett

Imperial College Business School

The quest for profit can never be the sole goal of business. Marrying multiple objectives together three-dimensionally is the route to business success.

I blame Milton Friedman. Great thinkers have a tendency to set the terms of a debate, and so determine what's up for discussion and what should be passed over in silence. In 1970, the Nobel Prize-winning economist wrote an article for The New York Times entitled 'The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits'. Its forceful argument against the possibility of business doing well by doing good helped create the modern Corporate Social Responsibility movement, aimed at specifically rebutting his thesis. In this essay, I hope to show how successful this movement has been: there is good evidence to show that brands can maximise profits and be a force for social good at the same time. But it is testament to the power of Friedman's thought that we are still using his terms of reference to frame our questions – even this one. He may have lost the battle, but if we are not careful, he will have won the war.

I blame Milton Friedman. Great thinkers have a tendency to set the terms of a debate, and so determine what's up for discussion and what should be passed over in silence. In 1970, the Nobel Prize-winning economist wrote an article for The New York Times entitled 'The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits'. Its forceful argument against the possibility of business doing well by doing good helped create the modern Corporate Social Responsibility movement, aimed at specifically rebutting his thesis. In this essay, I hope to show how successful this movement has been: there is good evidence to show that brands can maximise profits and be a force for social good at the same time. But it is testament to the power of Friedman's thought that we are still using his terms of reference to frame our questions – even this one. He may have lost the battle, but if we are not careful, he will have won the war.

Friedman's argument is very simple. Managers of businesses are employed to make money for their shareholders. The resources that they manage do not belong to them, but to their employers. As a result, all the decisions they make in their professional capacity should be judged on a single dimension: how they further the financial interests of their employers.

The response to this argument from kind-hearted businessmen and the academics they funded was swift and committed and, eventually, convincing. Forty years later, we have a wealth of research that shows how businesses can do well by doing good, and may, in fact, do better. A recent meta-analysis by Joshua Margolis at Harvard University, Hillary Elfenbein at Berkeley and Jim Walsh at Michigan University analysed the results of 167 separate studies into the financial impact of corporate social responsibility in general. They found that the performance of 'ethical' companies tends to be superior to 'unethical' companies, particularly over the long term. Regression analysis shows that around 13% of the abnormal performance of these companies can be put down to the effects of their CSR policies. Different 'good works' vary in their effects. Giving money to charity, for instance, seems to be a more effective business tactic than 'environmental policies' or 'transparency' (though both these activities result in positive returns). Only 2% of the studies cited showed a decline in shareholder value as a result of the adoption of ethical policies. But, as the researchers wearily note in their conclusion, anyone who wants to conduct the 168th study into the economics of doing well by doing good needs to go deeper than simply demonstrating a correlation.

This is exactly what the 168th study has attempted to do. A joint team of researchers at Harvard and the London Business School constructed an A/B test of two population groups that were similar in every way save for the fact that one group was 'high sustainability' and the other group 'low sustainability'. Over an 18-year period from 1993 to 2011, the 'high sustainability' group outperformed their 'low sustainability' doppelgängers by an average 4.8%.

The reasons for this superior performance are varied. The good guys seem to be able to attract and retain more talented staff; they attract longer-term investors (which, in turn, pushes down their cost of capital); they can ride out negative publicity with greater ease; and, at least for B2C companies, they command greater brand loyalty.

There is, of course, the thorny question of causation. Is it the niceness of companies that drives their success, or is it only successful companies that can afford to be nice? But perhaps this wrinkle can be smoothed out by the market. If ethical behaviour is strongly correlated with superior stock performance, investors will look to ethics as an indicator of future performance and, over time, a reputation for ethical performance will result in an increased share price.

Another question arises about time horizons. The sustainable companies were more successful in the long term, but their less ethical counterparts might outperform them in an individual year. Not every company can afford to be 'long-term greedy'. However, given the recent performance of the premature profit maximisers in Anglo-Saxon economies when compared with their more patient contemporaries in Germany or China, investors are beginning to reward 'sustainable' business models. Warren Buffett didn't make his billions wheeling and dealing on a day-to-day business.

It looks like we can have our cake and eat it. It is an axiom of modern finance that managers maximise profits by maximising net present value (NPV). Research has shown that good works are NPV-positive, ergo brands can maximise profits by being a force for social good. Your company is happy, society is happy, the fund managers are happy, Milton's happy. Everyone is happy.

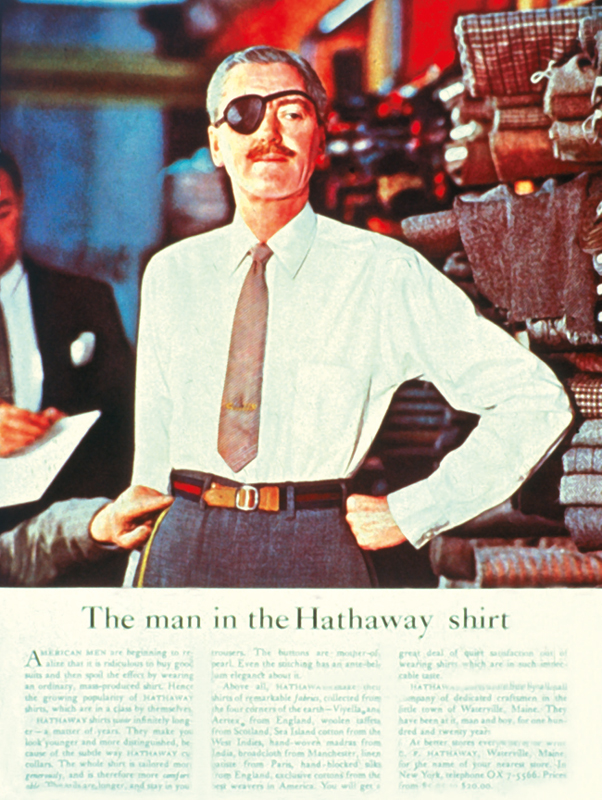

The role of brands publicising these good works is even clearer. Charitable acts may even be a more effective means of gaining a brand cut-through: when David Ogilvy created the Hathaway Man, his primary interest was in selling shirts, not improving the lot of the partially sighted. If a pretty girl (or a gorilla in a jockstrap, as Ogilvy's writing partner would say) would have worked better, then that's who he would have used. Brands want to make a connection with their target audiences; if the target audience cares about social good, then it pays for the company to show its interest too. In this schema, good works are no longer the responsibility of the CSR budget, but come under the marketing budget or the operations budget. They are not donations, but investments.

But there's a couple of problems here. The first is a question of authenticity. If your 'social marketing' is designed to benefit you just as much as the cause you are supporting, then it ceases to be a good act, and becomes, well, just an act. To be fair, even Friedman disapproved of using the 'cloak of social responsibility' to maximise profits. Honest businessmen, he wrote in his 1970 article, should 'disdain such tactics as approaching fraud'. They say that hypocrisy is the tribute that vice pays to virtue. Yeah, but it's still hypocrisy.

The second objection is more prosaic but probably more important. If brands can be a force for social good when it pays them to be good, does that mean that they don't have to be good if such projects are NPV-neutral or NPV-negative? We see brands clamour to associate themselves with Susan G. Komen or Cancer Research 'because it's something our customers really care about'. But what about the good causes that they don't care about? What if your customers don't care about social causes at all? What happens if they stop caring about them? In a recession like the one we are currently living through, money is tight and consumers often can no longer afford to pay an 'ethical premium'. In such a situation, your ethical advantage becomes an ethical albatross. If you're not getting anything out of it, then why are you putting anything into it?

We know what Friedman would say. Companies exist to maximise profits. If good works don't help in that endeavour, then you should not engage in them. In fact, you have a duty not to engage in them. As he says at the end of his article: "There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities to increase its profits, so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud."

And in his own terms, Friedman would be right. If your sole purpose is to make money, then everything that is not concerned with making money is an 'externality'. Nothing else matters when money is everything. Now, I like hard-headed arguments based on realistic thinking as much as the next man. Friedman's argument is certainly hard-headed. But it's not very realistic. You can choose to represent the world in black and white, but let's not pretend there's no such thing as colour.

In the real world — the 'real' real world, rather than the mathematical abstraction created by the Efficient Market Hypothesists – business does much more than make money. Simple empirical observation would suggest that firms exist to generate cash, but also generate status and security for those who work within them. Some exist specifically to solve a problem, and see the money they are paid as the by-product of the value they create. Others subsist simply for the sake of giving people something to do. Some people go into business to keep a family tradition going. Other businesses are started in a fit of pique, with the express aim of doing something different. There are innumerable motives for going into business. The making of money ranks high among them, but it is a necessary rather than a sufficient condition.

This is only to be expected because business is the product of people, and people are motivated by money – and other things at the same time. I can't tell you what motivates people. Different things – and different combinations of things – motivate different people in different ways. It's a mixture. But that's the point. It's not one thing. Without knowing what all the motivations are, we can still be suspicious of those who claim that there is only one of them.

The man in the Hathaway shirt': when David Ogilvy created the Hathaway Man, his primary interest was in selling shirts, not improving the lot of the partially sighted

In place of such 'thin' thinking, I propose that we start thinking a bit more realistically: thinking in 3D, if you like. People have more than one motivation, businesses have more than one motivation. If that is true, let's just be honest with ourselves. You and I decide to start a business together. In this business, we might want to (a) create sustainable profits, (b) work towards the eradication of TB, and (c) get home from work on time. Each objective is valid, in and of itself. They are not subordinate to one another, but may require trade offs: (b) and (c) won't happen at all if (a) is missing. But at least we're honest about the fact that we have three (and perhaps eventually more) objectives, and that they may well be independent of one another. Once we know that we have more than one objective, we can have a realistic conversation about how (and whether) they fit together. We can also judge the success of each objective in its own terms, without having to use the language of the first objective (usually money) to discuss the others.

Of course, it may be that, on consideration, you and I, jointly and severally, decide that the only thing that matters to us is the making of money (although in that case, I think it might be prudent to explicitly promise that we will 'engage in open and free competition, without deception or fraud', because you might have doubts about my character). If that is the case, so be it. I applaud our honesty, though I also doubt our ability to attract either partners or customers. But once the ink is dry on our shareholders' agreement, the questions begin. Then, and only then, will we have to manage the ethical dilemmas that arise from having to pursue our 'primary obligation to maximise profit and shareholder value' in a complicated world. Then, and only then, will we have to justify every good act by its ability to generate a positive NPV. Then, and only then, will we have to even ask the question, 'can we do well by doing good?'

The future, we are told, is already here, it's just that it isn't evenly distributed. Thinking in 3D is the same. 3D companies already exist, and perhaps have always existed. For those who work in the advertising industry, our task is to find them, and work with the ones that we agree with. Different companies will have different sets of objectives and different cultures. Not all of them will appeal to all of us. Intelligent people can have different opinions. That is fine. But one thing we can all agree on is that we should avoid working for one-dimensional clients.

Clients motivated solely by profit are a bad bet. If the research quoted earlier is anything to go by, they are unlikely to be in a position to pay performance-related bonuses, and their difficulties hiring and retaining good talent at their end will make for a future filled with interminable conference calls that ultimately resolve nothing. As an outside agency, you will never change them, but they may change you. Don't work for them. Don't pitch for their business. Let the dead bury their dead. This assumes that we are part of the solution rather than being part of the problem.

But what about your own company? How 3D is its thinking? Do you even know what your own company's objective(s) are? For instance, how pro bono is your pro bono work? These are important questions, which we raise of our clients' businesses, but rarely apply to our own.

Friedman was wrong about business' role in promoting social good. He was wrong in detail, but, more importantly, he was wrong in his guiding assumptions. We have focused on the details, and worked hard to remove the mote he put in our eye, but the beam remains. Of course, brands can, and do, maximise profits while being a force for social good. The real question is whether maximising profits is, or should be, the only aim of business. As Bill Bernbach once said, a principle isn't a principle until it costs you money. If money is all you care about, you can't afford to have principles.

Judge's quote

It had a strong central idea: companies have different objectives and these require trade-off, which is a more practical way of thinking about policy than a Balanced Scorecard.

— Colin Mitchell, Admap Prize judge

Mike Follett began his career at BMP, before moving to New York and Mumbai, to help set up DDB India. He returned to London to work on Tesco with The Red Brick Road, and is now studying for an MBA at Imperial College Business School.

michael.follett12@imperial.ac.uk